North Korea: Defectors adjust to life abroad

- Published

Life inside North Korea's closed borders is hard to imagine. One of the only insights into how ordinary people live, beyond the official line of the regime, comes from those who have escaped. Two defectors, Chanyang Joo and Yu-sung Kim, who left North Korea in 2011, tell their story.

"I heard that people sold and ate human flesh," says Chanyang Joo. "I heard they were killing other family's babies and selling the flesh after burying the head and fingers."

Ms Joo says she ignored the rumours until the parents-in-law of a man she knew were publicly executed. They were butchers and the crime, people said, was selling human meat.

Rumours like this have surfaced in the testimony of several defectors coming from North Korea. Whether they are true or not - and we may never know - the fact that they circulate and are believed illustrates the level of hunger, deprivation and fear in parts of the country that marked the Great Famine.

Fellow defector Yu-sung Kim heard these rumours too and believes there may be some truth in them. "When I was in university that had happened," he says. "It's due to hallucination caused by severe hunger, people don't even realise the act as murder and eat the flesh. But that is very, very rare."

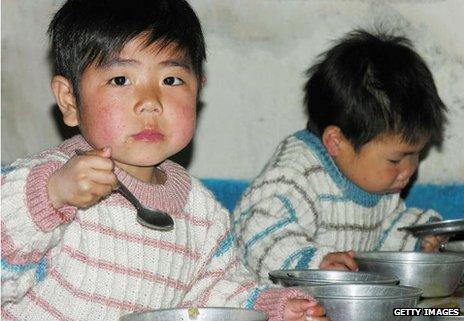

The rumours started during the Great Famine, from 1994 to 1998, when grain shortages in China meant food aid was drastically reduced. Sober estimates say that 600,000 to one million people died during the famine - about three to five per cent of the population of the country.

"It was the most destructive famine of the 20th century," says Marcus Nolan, author of Famine in North Korea. "The idea that people are sufficiently desperate and unhinged is not surprising."

Chanyang Joo was just a toddler when her family moved from a city to the rural village where she grew up. It was during the famine, when markets closed and transportation failed. Many in the cities died of starvation, she says, but in the countryside her family survived on vegetables and shrubs.

After the famine they were still very deprived. "We couldn't get any medicine," she says. "Very rarely some medicine was brought from China. Doctors sometimes performed surgery without anaesthesia. I saw some emergency patients dying."

But some North Koreans like Yu-sung Kim and his family were entirely unaffected by the famine. His parents earned money by trading illegally with China and South Korea and arranging for separated families to reunite across the Korean border. He grew up in a government-owned high rise apartment, watching movies and playing video games that were smuggled across the border from the South.

As children, both Kim and Joo learned to worship the regime and its founder Kim il Sung. "The first sentence we learn as a child is 'Great father Kim Il Sung, thank you.' and 'Dear leader Kim Jong Il, thank you,'" says Joo.

"We have to thank the leaders for everything. Every school, every classroom, even the train cars have the pictures of leader Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il on display."

From preschool to university this is the most important subject for a young North Korean. "You can fail everything as long as you know about the history of the Kim family," says Joo.

But she had happy memories too. "Until North Korea's brainwashing education takes effect, children are children," she says. "When I was little and unaffected by politics, I had the most fun playing with my friends."

Though his childhood was privileged and the illegal trading of his parents was overlooked by the regime, Yu-sung Kim and his family knew they had to toe the line when it came to certain rules.

They couldn't watch any news from outside Korea and any criticism of the regime was forbidden. He could discuss politics with his family but not with anyone else. "There is always a government spy in a group of people more than three," he says. "You could end up in a political prison camp."

Joo's family had first-hand experience of these camps. Her grandfather spent nine years in one. He had criticised the regime while with a group of friends but there was a spy in the group and he was arrested. "It was a simple slip of the tongue," she says.

He told his grand-daughter of horrifying conditions at the prison camp, of people eating rats and digging grain from animal faeces to survive. He said prisoners were attacked by dogs as punishment and dead bodies were left to rot where they fell.

Her grandfather's experience had a profound effect on the entire family, though not in the way the regime intended. At the camp he interacted with prisoners from the elite classes and learnt of the inequality in North Korea and of life outside the country.

"My grandfather had always told us we had to leave for freedom," says Joo. "He said 'Dream big' and that if we wanted to live in the real world, we had to leave."

"Since I was little, I strongly felt the need to leave. I've never touched a computer but I was really curious about them. I loved studying and was good at it so I wanted to learn as much as I wanted in a free country."

For seven years, her family plotted to leave North Korea. They listened to radio broadcasts from the South. When this came to the attention of the authorities in 2008 it was time to go. Her father left first through China and Laos to the South Korean embassy in Bangkok. He saved to pay brokers to help the rest of the family escape.

Ms Joo was the last to defect and when authorities found out that her father was missing, she was put under investigation. She told them he had died in a fishing accident. "That is common in North Korea," she says.

She practised swimming and trained physically for her escape. Three years later she crossed the border to China where she was arrested. China doesn't recognise North Korean refugees and its official policy is to send them back. But defecting is a very serious crime and repatriation means imprisonment, torture or even death. A religious group, which she cannot name, helped release her from jail.

For Yu-sung Kim and his family, the decision to leave North Korea came suddenly. His father's business came to light in a South Korean newspaper in 2011, fearing the government reaction they fled. They left behind his younger sister who was ill. He later found out that she was told her family had been captured and killed while attempting to escape. She later died in North Korea.

North Korean defectors protest about China's policy of repatriating defectors

Though he appreciates his freedom Mr Kim says life in Seoul is difficult. He faces prejudice from South Korean society which often considers North Koreans, with their archaic dialect and strange accent, as ignorant and backward.

"In my university when I tell people where I'm from they see me as strange, like an alien from the Moon," he says.

There are more than 24,000 North Korean defectors living in South Korea. When they arrive many lack the basic skills to live and work in a modern society - operating a cash machine, driving a car, using a phone or a computer.

They find it hard to get work and some resort to petty crime which has given the community a bad name. "I sometimes think living in South Korea is fortune and misfortune at the same time," Mr Kim says.

Chanyang Joo refuses to let prejudice bother her. But she says freedom has its own problems.

"There are too many things to do here and I have to plan my own life and it's stressful," she says.

"But when I think about the difficulty of living in a free society, I realise I'm working and getting tired for myself and for my future so I feel happy."

Chanyang Joo and Yu-sun Kim spoke to World Have Your Say on the BBC World Service. Listen to the programme here.