Boston bombings: How to interrogate a suspected terrorist

- Published

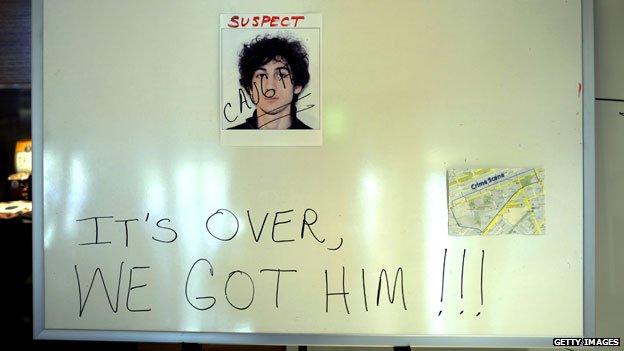

People all over the world want to know whether - and why - a pair of immigrant brothers set off two bombs at the Boston Marathon last week. And a highly trained team of US interrogators are waiting for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev to tell them.

The best interrogation tool is a can of Coke on a table.

ME "Spike" Bowman, a former deputy general counsel for the FBI, says offering a suspect something he wants - whether a can of Coke in the beginning or a reduced sentence later - builds rapport.

Once the interrogator establishes a bond with the suspect, things become easier.

"You talk to people who are friendly," Bowman says.

Whatever methods the interrogators in the Boston Marathon bombing investigation have used so far, they appear to have been successful.

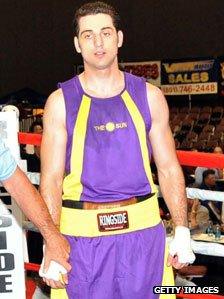

Dzhokhar's brother Tamerlan - pictured in his boxing days - died last week

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the 19-year-old sole suspect, has begun to open up.

He is in fair condition at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. In a hospital room, he has reportedly said that he and his brother, Tamerlan Tsarnaev, 26, acted alone.

His brother, killed as police closed in on Thursday, was the driving force behind the attacks, he said.

He said Tamerlan Tsarnaev wanted to "defend Islam", a government official told CNN, external about the hospital interview.

The FBI would neither confirm nor deny to the BBC the reported details of the interrogation.

If Dzhokhar Tsarnaev has indeed revealed information about the attacks, it is a victory for the officials.

Some of the questioners are part of a top US investigative team known as the High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group, created in 2009 by presidential order.

It is composed of "mobile teams of experienced interrogators, analysts, subject matter experts and linguists to conduct interrogations of high-value terrorists", according to government documents.

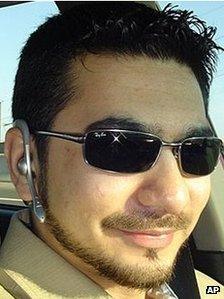

Group members interrogated Faisal Shahzad, who is serving a life sentence after pleading guilty to trying to set off a bomb in New York's Times Square in May 2010, CIA Director John Brennan has confirmed, external.

Faisal Shahzad pleaded guilty to trying to set off a bomb in New York

The group was originally designed to have specially trained interrogators ready to go to work on Osama Bin Laden if he were ever captured, says a forensics expert who is familiar with the group and who asked not to be identified because he has a government security clearance.

"I don't want to say it's overkill in this case," he said of the group's deployment in the Tsarnaev investigation. "The bureau wants to bring out their shiny new toy."

As High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group investigators gather information on the case and await more time at Tsarnaev's bedside, doctors and nurses have tried to make the suspect comfortable - or as comfortable as someone suffering from multiple gunshot wounds can be.

The interrogators' approach seems humane, particularly compared to the way other government officials have treated terrorism suspects in the past.

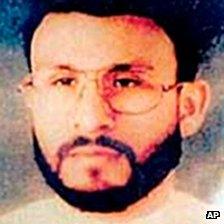

Years ago CIA officials reportedly used harsh interrogation techniques , externalon a wounded terrorism suspect, Abu Zubaydah, a top al-Qaeda operative. They reportedly stripped him of his clothes, kept him in a cold room and subjected him to waterboarding.

Video the CIA recorded of his interrogation and detention reportedly showed Zubaydah screaming and vomiting.

He apparently told them little of value. Later, FBI special agents tried to make him comfortable - and over time learned a lot about the terrorist organisation. People from the CIA, FBI and other agencies are still arguing about the circumstances of Zubaydah's interrogation.

Nevertheless, FBI agents' traditional approach - learn as much as possible about a suspect and the case and then build trust - reflects the bureau's intelligence gathering philosophy.

Abu Zubaydah was reportedly first waterboarded then made comfortable

"The interviews that are the most successful are the ones when the interviewer has nine-tenths of what he needs," says Mike German, a former FBI agent who has worked undercover on domestic terror cases. ("I recovered a lot of bombs," he says.)

German and other experts believe that more aggressive methods, such as beatings and humiliation, are less effective.

Setting aside moral and ethical issues, they say inflicting pain is rarely a good interrogation strategy.

"People don't react well to coercive methods," says Bowman, the former FBI lawyer.

He describes another interrogation of a recalcitrant suspect. Military interrogators tried to get information from Brooklyn-born Jose Padilla after he was arrested in 2002 and accused of plotting a "dirty bomb" attack in the US.

"They interviewed him for six months and got absolutely nothing," says Bowman. "The FBI got a crack at him and he was talking in four hours."

Padilla was convicted of terrorism conspiracy in 2007.

The Padilla case, like other domestic terrorism cases, is complex. Government officials dispute criticism the case was handled inefficiently. And years later, the Padilla case is still controversial, and questions about it remain unanswered.

Still, kindness is not the only way. Interrogators must tailor their approach to the individual suspect, who may indeed require more aggressive treatment before opening up, experts say.

"If he's a meek kind of guy, and you send in a 6ft-tall, football-player-type interrogator, screaming, 'A year from now you're going to have a needle in your arm, and you're doing to be dead', he might just melt and tell you everything," says the forensics expert.

In Tsarnaev's case, the investigators are in a strong position - and may not need to yell.

"The interrogation could help to fit in a few details," says German. "But for the most part the information is well known."

The forensics expert agrees: "To be honest, they don't need him to tell them everything he knows. But it would be nice."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published9 May 2012

- Published23 April 2013

- Published22 April 2013

- Published22 April 2013

- Published23 April 2013

- Published22 April 2013

- Published23 April 2013

- Published22 April 2013

- Published30 January 2014