Is there really a north-south water taste divide?

- Published

BBC News brought together three experts for a tap water taste test

Every year a slew of US localities fight over who has the tastiest tap water. These blind tasting competitions are yet to take off in the UK, but many would stick up for their tap water as the best.

There are many things that divide the north and the south of Britain - politics, the weather - but water is probably the oddest.

You'll often hear people extol the virtues of drinking water that originates from their area - whether it's the Lake District, the Pennines, Welsh Hills or Scotland's Highlands.

Northerners protest about having to drink London tap water, but then there are Londoners who swear the city's "hard" water is superior to areas with "soft".

But is there any science behind these taste preferences?

Fundamentally, tap water across the UK is highly regulated and among the safest in Europe. But that doesn't necessarily cover taste.

The reason why tap water tastes different is a heady mix of geography, science and subjectivity.

Water is described as a universal solvent because it can dissolve a wide range of compounds, explains Mindy Dulai from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

So most water, she says, will contain certain ions, such as calcium and magnesium, even if it's just a trace amount. These minerals are the main ones that define whether water is hard or soft, and they play a role in the taste.

"They are fairly common to different types of geology," she says. "Limestone, for example, is a calcium carbonate.

"But apart from minerals dissolving in water, dissolved gases can also play a role."

As a chemist, Dulai says there shouldn't be a huge variance in the taste of drinking water in the UK. But people's experience of the "taste" of water comes down to a few main aspects.

Hard water may make people experience a "chalky mouthfeel", she says, while chlorine, which is widely used as a disinfectant in the water-treatment process, can give off a particular taste.

Naturally occurring organic compounds, such as humic acid, sometimes react with chlorine and can create an antiseptic or astringent taste.

Most tap water tends to come from two main sources - surface water from lakes, streams and rivers, and groundwater. Surface water tends to be soft, containing fewer minerals, and acidic by nature, while groundwater tends to be harder. Water suppliers sometimes blend the two and the mix" could change from one day to another.

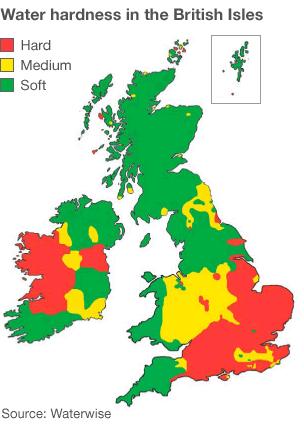

According to Waterwise, an imaginary line could be drawn from The Wash on the north-west margin of East Anglia, to the Bristol Channel, with groundwater more abundant to the south and east - except for Devon and Cornwall - and surface water to the north. They are also the lucky ones who don't get much limescale on their kettles and can whip up a good lather.

Soft water is thought to have less of a "taste" than hard. But what exactly is it that people appear to "taste"?

"Like any food and beverage, we bring our personal sensitivities to tasting water, and this can be to do with genetics, age and experience," says Dr Andrea Dietrich, professor of civil and environmental engineering and a water tasting expert at Virginia Tech in the US.

When people talk about the taste of tap water, she says, they are not being quite accurate. "Taste" is often confused with "flavour".

Flavour is a mixture of sensory information - taste, smell and the tactile sensation that is known as "mouthfeel" (so you might experience water as feeling "light" or "heavy" in the mouth).

Four basic taste sensations are recognised by our taste buds - bitterness, sourness, sweetness and saltiness. But, according to Dietrich, we can detect something like 10,000 odours.

Sourness is not associated with water, but bitterness, for example, can be caused by magnesium chloride and calcium chloride.

When we swallow, volatile odours are pushed back into the nose, the taste of, say minerals, and odours from naturally occurring compounds combine to create flavour, she says.

So what flavours then might people experience with water?

Softer water, says Dietrich, can have a different "ecology" to hard water.

"There are two classes of organism in water - the cyano bacteria, which is commonly known as blue/ green algae, and actino mycetes, which are responsible for the damp or earth smell."

"What people describe as an earthy or musty 'taste' will usually occur in water as a by-product of the ecology."

Given that odours can cue recall of a memory - an "earthy" flavour might evoke the joys of the hills and valleys to one person, but an unpleasant damp-in-the-basement experience to another.

And, some people are more highly tuned when it comes to the senses.

"Sense, taste and smell and vision and hearing have a normal range, but there can be a hundred-fold between the ability of people to discern a taste or odour - it's not uncommon," says Dietrich.

People's approach to tap water is "highly subjective", says Glasgow University water engineer Prof Paul Younger, author of Water: All That Matters.

"It almost doesn't matter how it tastes, it's more about what the individual is used to," he says.

Take as an example an area of Co Durham and southern Sunderland, he says. Like much of the north, the area has soft water, but there are significant areas where, due to the local geography, some of the water is supplied from groundwater in limestone.

"Where the two areas are adjoining, sometimes the same supplier has to switch supplies for operational reasons," says Younger. "Whichever way around it is - from hard to soft or soft to hard, there are always people who ring up to complain about the different tastes. It's really about whatever one you are used to.

"There is not objectively good-tasting water. There is, however, an objectively bad-tasting water," he says.

Is that tap?

Chlorine is the taste that people really complain about, says Younger.

"People are most likely to kick off about the taste of water if they live near a treatment plant," says Younger. "What they are tasting is the residual disinfectant, which is needed for water to stay potable - not just when it leaves the tap but if it sits in a glass for a few hours."

There is a minimum dosage requirement, but extra might be added at source because chlorine declines over a distance. Those living close to a treatment plant, he says, might experience a stronger taste.

Some people are more sensitive to the taste or smell of chlorine, with the chemical imparting a slightly acidic taste.

The subjective nature of water tastes has been revealed regularly during taste testing, says Arthur von Wiesenberger, author of several water books and a water master at the annual Berkeley Springs International Water Tasting, external competition in the US.

He reckons that we form subconscious memories of water. At a blind water tasting held by The San Francisco Chronicle in 1980, a highly mineralised, non-carbonated French bottled water was hidden among the tap water. It scored poor marks with all of the judges except one, who was French. For him in was the best-tasting and he commented that the water reminded him of home.

According to Wiesenberger, this demonstrates that our taste buds and brain have a strong recall, even with the subtle taste of water.

"We have found at our tastings over the years that people have fond memories of water. I have heard people waxing on about the 'pure' tasting water from grandma's well."

But while subjectivity plays a big part, there are particular waters that always seem to come out top - even though the panel changes every year.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external