The rise of CCTV surveillance in the US

- Published

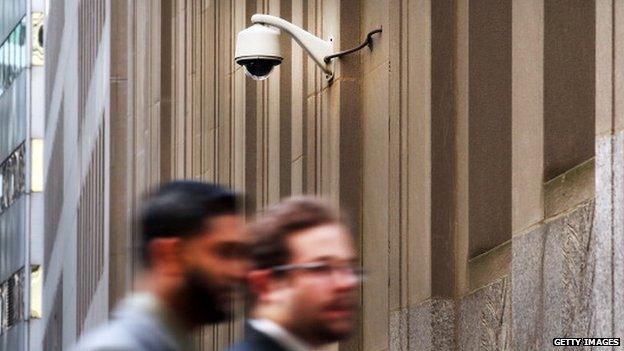

New York has one of the most sophisticated surveillance systems in the country

The Boston Marathon bombings suspects were quickly identified after investigators picked them out on CCTV footage. Does that mean Americans need to depend more on CCTV?

Before they were Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, they were Black Hat and White Hat - two young faces in baseball caps, identified in grainy video footage as the prime suspects in the Boston Marathon bombings.

From footage totalling hundreds of hours, investigators singled out the two men from a sea of marathon spectators, then followed their movements before and after they allegedly planted the two bombs.

Those bombs would kill three people and wound more than 200, and Black Hat and White Hat were identified soon after their images were released. A day later, one was dead and the other in hospital.

The crucial role that video footage played in this case has many Americans re-evaluating the role of CCTV and other surveillance tools in public spaces.

While the US never embraced state-sponsored CCTV the way the UK has, it has nevertheless used surveillance as a national security and law-enforcement measure for years.

"As the Boston bombing demonstrated, we are pretty well surveyed," says Ioannis Pavlidis, a professor of computational physiology at the University of Houston.

That surveillance comes from a mix of private and public video cameras. Pavlidis, who worked in the private sector before turning to academia, says his projects were funded both ways.

"Part of our funding [into surveillance technology] was coming from a government agency who was interested in developing more of this kind of technology," he said.

"There was government interest, but at the same time there was private interest. And they coincided."

For the most part, surveillance in the US has been led by private citizens.

In the 1980s, video technology became cheap enough for individual businesses and citizens to install their own home security systems. By the '90s, that technology improved, leading to more digital footage with better quality.

Private video footage has been used in public security, in cases such as the Rodney King beating, where a citizen caught police assaulting King on tape.

Then came the attacks on the World Trade Center.

"The thing that was really prompted by 9/11, on top of the general trend, is the introduction of the police-run cameras," says Jay Stanley, a police analyst for the American Civil Liberties Union.

New York City boasts an impressive system designed not just to identify criminals after the fact but catch them in the act.

"All of these cameras feed back into a command centre that has very significant analysis capabilities on the back end, including real-time video analytics on the feed," says Dan Verton, editor of Homeland Security Today.

"A bag left unattended would be automatically picked up by the system."

Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev's movements tracked with surveillance footage and private video

Police can then be deployed to troubled areas caught on film, allowing the force to do more with fewer officers.

"The mission is to have just a few officers being able to cover arguably the entire city wherever there's a camera, and redirect resources - police on the street - to areas where they are needed as opposed to having to blanket the street with officers," says Verton.

New York City Police Commissioner Ray Kelly has been outspoken in his support of surveillance cameras after the Boston bombing.

"The people who complain about it, I would say, are a relatively small number of folks, because the genie is out of the bottle," Kelly said on MSNBC television. "People realize that everywhere you go now, your picture is taken."

Indeed, most experts predict more surveillance in the years to come.

"That's the way of the world and where the technology is going," says Pavlidis, who cites the introduction of Google Glass.

"That will be one more surveillance mode in everyone's face. Social media, phones with cameras everywhere... there's no escape."

For privacy advocates like Stanley, however, there is a big difference between footage taken by private citizens and collected by the police in an emergency - and footage taken by police as part of a larger blanket campaign.

When large-scale surveillance systems like the ones in New York are in place, he says, "You can track individuals through time and space in a way that you can't when cameras are privately owned."

"You can collect [private] video quickly and easily if you need it, but it doesn't allow for the many abuses we fear if you turn all of our public spaces into centrally monitored ones," he says.

Americans have proven resistant to such measures in the past. The use of drones as a surveillance measure has been roundly criticised, says Verton, with several planned programmes put on hold due to privacy fears.

A recent poll showed that only 40% of Americans supported more cameras, external in the name of public safety - and only 12% wanted fewer cameras.

And yet, more cameras are coming. Police officers in Denver, Phoenix, Chicago and other cities are relying more on surveillance video to help fight crime.

For Ioannis Pavlidis, the technology is inevitable. But it is also neutral.

"It's the interpretation that makes the difference," he says. "If democratic institutions work well and it is used judiciously, it can make us safer."

And if not? Privacy advocates are like Stanley are watching the watchers, hoping to stem back the tide.