Amanda Knox and prison life

- Published

A primetime television interview and a new book have put Amanda Knox's experience of prison life in Italy back under the spotlight. But do these accounts tally with what she said at the time?

In the weeks leading up to publication of Amanda Knox's memoir, Waiting to be Heard, descriptions of her four years in a Perugia women's prison as a "trauma in an Italian hellhole of sex and debauchery" - as the National Enquirer put it - have become increasingly lurid.

Knox's memoir is a vivid personal account of the difficulties of prison life in Italy, complete with claims about inappropriate behaviour by staff. But Knox herself once painted a different picture.

Other documents - including writings Knox penned in her own hand while incarcerated, case files and state department records - conjure up quite another impression of a very different Knox, one who was more sanguine about her experience.

"The prison staff are really nice," wrote Knox in her personal prison diary, which was eventually published in Italy under the title Amanda and the Others.

"They check in to make sure I'm okay very often and are very gentle with me. I don't like the police as much, though they were nice to me in the end, but only because I had named someone for them, when I was very scared and confused."

She described Italian prisons as "pretty swell", with a library, a television in her room, a bathroom and a reading lamp. No-one had beaten her up, she wrote, and one guard gave her a pep talk when she was crying in her cell.

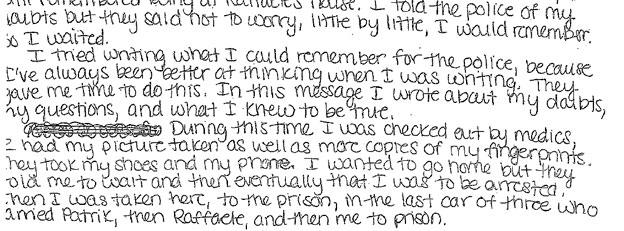

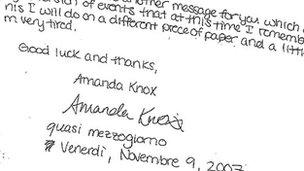

Unlike the heavily-edited memoir, these are phrases she handwrote herself, complete with strike-outs, flowery doodles, peace signs and Beatles lyrics.

The prison diary and Waiting to be Heard match up to an extent, and she cites some passages of her own diary.

Knox recounts in her diary early on that a male prison guard winked at her when she got letters from men, often brought up her sexuality and gave her the impression he was making a pass at her.

Both accounts also refer to the devastating but erroneous news from the prison doctor that she had tested positive for HIV, although her diary presents a more relaxed person at this point. "First of all, the guy told me not to worry, it could be a mistake, they're going to take a second test next week."

But there are discrepancies between her memoir and her own descriptions early on in the case of why she made certain written declarations to police.

In the memoir, Knox describes getting emotional as she watched the footage of the man she initially blamed for the murder, Patrick Lumumba, walking out of prison as a free man and standing with his wife and baby after he was cleared.

Amanda Knox: "For all intents and purposes I was a murderer, whether I was or not" - Courtesy ABC

She writes that she had a flashback to the interrogation, when she felt coerced into a false accusation. "I was weak and terrified that the police would carry out their threats to put me in prison for 30 years, so I broke down and spoke the words they convinced me to say. I said: 'Patrick - it was Patrick.'"

In her memoir, she describes in detail the morning that she put that accusation in writing, and says the prison guard told her to write it down fast. Yet in a letter to her lawyers she gives no hint of being rushed or pressured. "I tried writing what I could remember for the police, because I've always been better at thinking when I was writing. They gave me time to do this. In this message I wrote about my doubts, my questions and what I knew to be true."

There is a similar contradiction a few paragraphs later, when she describes in harrowing terms the trauma of an examination at the police station.

"After my arrest, I was taken downstairs to a room where, in front of a male doctor, female nurse, and a few female police officers, I was told to strip naked and spread my legs. I was embarrassed because of my nudity, my period - I felt frustrated and helpless."

The doctor inspected, measured and photographed her private parts, she writes - "the most dehumanising, degrading experience I had ever been through".

But in the 9 November letter to her lawyers, she described a far more routine experience.

"During this time I was checked out by medics. I had my picture taken as well as more copies of my fingerprints. They took my shoes and my phone. I wanted to go home but they told me to wait. And that eventually I was to be arrested. Then I was taken here, to the prison, in the last car of three that carried Patrick, then Raffaele, then me to prison."

She says she was often suicidal, but recollections of prison staff and other inmates differ. Flores Innocenzia de Jesus, a woman incarcerated with Amanda in 2010 described Knox as sunny and popular among the children who were in Capanne with their mothers, and recalled her avid participation in music and theatrical events. She also held a sought-after job taking orders and delivering goods to inmates from the prison dispensary.

"Most of the time when we spoke during our exercise break, the kids would call her and she would go and play with them," de Jesus told me.

Knox describes frequent prison tensions. According to de Jesus, there was resentment because she was seen as "a detainee with special status" due to frequent visits from influential Italian politician Rocco Girlanda, who brought her books, computers and other prized items.

"She knew she was envied, but because she was very intelligent, she was able to have a rapport with the detainees, especially those who envied her, in a very spontaneous way," says de Jesus.

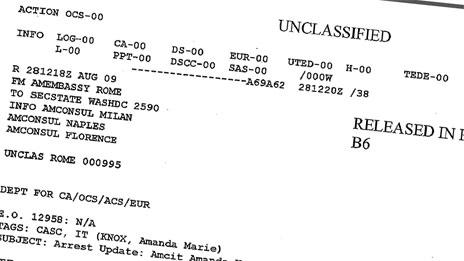

State department cables, released through the Freedom of Information Act, show that between 2007 and 2009, three different high-level diplomats from Rome (Ambassador Ronald Spogli, Deputy Chief Elizabeth Dibble and Ambassador David Thorne) were among those reviewing Knox's case.

Embassy officials visited regularly. Records show one consular official visited Knox on 12 November, soon after her arrest.

A few weeks later she wrote in her diary how the visits of embassy officials improved her experience.

"I am reading a romance novel that the consulate brought me, and I'm actually enjoying it. Soaking it up. How sad is that? So it's come to this. I could definitely see myself interested in Oprah's book club, but cheesy romance novels? I must be really REALLY bored."

In 2008 and 2009, she was visited by two embassy officials at a time, six times. Ambassador David Thorne, whose name appears at the bottom of cables in August, November and December of 2009, is the brother- in-law of US Secretary of State John Kerry (at that time chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee).

If the diplomats knew anything of the "harrowing prison hell" Knox was going through (as one paper put it), they are keeping those reports under wraps. Neither Kerry nor any other prominent US politician has made any public complaints. Even today, her Italian lawyers maintain she was not mistreated.

With a new trial set in Florence in the coming year, a few key passages of "Waiting to be Heard" will most likely be heard once again, in an Italian courtroom.

Follow the Magazine on Facebook, external or Twitter, external.