The great dinosaur stampede that never was?

- Published

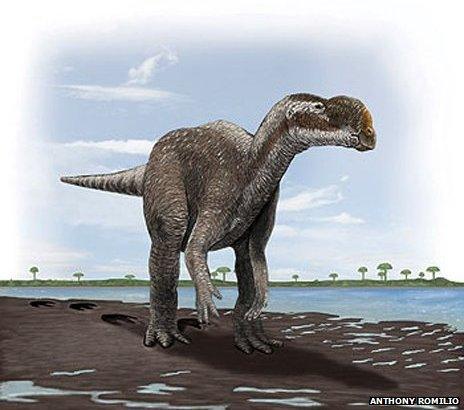

The stampede is thought to have involved a dinosaur similar to Tyrannosaurus rex

It's billed as the world's only known example of a dinosaur stampede - but new research is challenging the established version of events at Lark Quarry, in the Australian outback, almost 100 million years ago.

Rewind the clocks 95 million years, and imagine the scene.

You're at the edge of a watering hole in what today is north-eastern Australia. And you're not alone.

More than 100 little dinosaurs are here, ranging from the size of chickens to ostriches.

They're drinking peacefully, when - all of a sudden - a giant meat-eating dinosaur tears out of the brush. Its teeth and claws flash as it races in for a meal.

The little guys scatter for their lives - their feet digging into the soft mud. It's a dinosaur stampede.

"This incident would have taken five minutes, if that. It's a snapshot in time," says John Taylor, a tour guide at the Dinosaur Stampede National Monument, at Lark Quarry in central Queensland.

"This event that you can see right here before your eyes, you cannot find anywhere else in the world," he says, pointing to the fossilised footprints scattered across a giant slab of rock.

Thousands of visitors from around the world visit the site each year, and in 2004 it was added to Australia's National Heritage list.

The tracks were discovered in the 1960s by a quarry manager - who at first thought they must have been bird footprints.

In the 1970s, they were recognised as dinosaur tracks, and the area was excavated. More than 60 tonnes of rock were removed, revealing between 3,000 and 4,000 footprints, which in 1984 were identified by scientists, external as being the result of a dinosaur stampede.

The idea of the great stampede entered into dinosaur folklore. The Australian Department of the Environment says it provides "scientific underpinning, external" for the stampede scene in Spielberg's Jurassic Park - though a consultant who worked on the film denies it was the inspiration.

"Stampeding dinosaurs is a fantastic story," says Anthony Romilio, a graduate palaeontology student at the University of Queensland - and the young scientist now leading the challenge to the established version of events.

"People love dinosaurs - and what's more exciting than having hundreds of dinosaurs stampeding?"

But Romilio says the facts just don't seem to add up, and in a paper published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, external in January, he and his co-authors argue there never was a stampede at Lark Quarry.

The Muttaburrasaurus left footprints with stubby toes

Romilio didn't set out to challenge the traditional interpretation of the dinosaur footprints - he just wanted to work out how the dinosaurs moved their limbs.

But he found himself hitting a brick wall. "It took me about six months of pure confusion, going, 'Look, my research - it's just going nowhere,'" he says.

"My supervisor said: 'Look, just imagine you're the first scientist to come to the scene. How would you interpret it?'"

So Romilio took a fresh look at all those footprints, and he thinks the scientists before him misinterpreted the evidence.

First - remember that big, marauding dinosaur that thundered on to the scene? Romilio doesn't think it was a carnivore at all.

Footprints of meat-eating dinosaurs have characteristic long, narrow toe impressions, while those of plant-eaters are short-toed and quite broad - and, Romilio says, the tracks at Lark Quarry match the latter.

The most likely candidate, he believes, is the plant-eating dinosaur Muttaburrasaurus, external - known for its large knobbly nose, and big nostrils.

The smaller dinosaurs would have had little reason to run away from this plant-eater. Indeed, Romilio thinks the other dinosaurs weren't running at all - but swimming.

"This is one of the tippy-toe traces," he says, pointing at a 3D image of one of the tracks.

hires.jpg)

"Tippy-toe" prints could easily be left by a dinosaur buoyed up by water

Scientists had taken the large distance between each footstep as a sign the animals were running full speed, but Romilio argues that some are spaced out in this way because the animals were in water, and being buoyed along by it.

The dinosaurs were swimming in a stream - over days or even weeks, he believes - not fleeing from a predator in a panic.

His conclusions have sparked a lively debate among palaeontologists. Some scientists think Romilio is on to something - but he's got his critics too, external.

"Just simply looking at the footprints isn't enough," says Scott Hocknull, the chief dinosaur expert at Queensland Museum.

He says Romilio is confused because he didn't account for how the mud interacted with the dinosaurs' feet.

"When you look at the footprints, they look like big, round toes, when in fact, that's the mud being squished out from below the toes - between the toes - as the animal is slamming its foot into the mud."

Inside the museum's storage space, Hocknull wheels a mobile spotlight over to a cast of one of the big footprints, and lights it up from a low angle to reveal its subtle contours.

"See this triangular piece?" he says. "That's the claw mark. There's only one type of animal that makes those sorts of footprints - and that's a meat-eating dinosaur."

As for Romilio's argument that the little dinosaurs weren't running but swimming, that's very unlikely, says Hocknull - underwater, a footprint in mud just doesn't last.

"I don't want poor scientific process to get in the way of an amazing story," he says.

"If we simply just accept that all of the last 30 years of accepted stampede information, data and work is wrong - and that it's simply a Muttaburrasaurus wandering through some mud, and then a bit of a flowing river with some tracks - it really does take the significance out of the site."

Tour guide John Taylor is also sceptical of the swimming theory. For the moment, he's sticking with the stampede story, but he says he's willing to change his tune if necessary.

"If they have the evidence to back that up, then that's what we'll start telling people… because we're here as interpretive guides. We're not here to tell people our own personal beliefs."

Regardless of how the science pans out, he doesn't think it will affect tourism.

Lark Quarry remains one of the largest - and most impressive - concentrations of dinosaur footprints in the world.

Ari Daniel Shapiro was reporting for The World, external and the PBS programme NOVA, external. The World is a co-production of the BBC World Service, PRI, external and WGBH, external

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external