The Apprentice: A lesson from Sweden

- Published

With each new series of The Apprentice comes another epic salvo of boasting and braggadocio. This Anglo-American approach to "bigging up" your skills and successes is a far cry from how things are done across the North Sea in Scandinavia.

"When it comes to sales, I'm the best," says Natalie Panayi, one of this year's contestants on the British version of The Apprentice.

"I just feel my effortless superiority will take me all the way," confides fellow contestant Jason Leech.

They're already much in the manner of boasters from previous years. In series four, Jenny Maguire blurted out: "I rate myself as the best salesperson in Europe." In series five, Majid Nagra said: "I was born to do great things."

Many of the boasts are eye-wateringly idiotic, a guilty pleasure for viewers who wish to see hubristic young know-it-alls taken down a peg or two.

But while The Apprentice bragging may be a stereotype - and sometimes seems a scripted stereotype at that - they are a magnification of a real factor in society.

Many British people used to think of Americans as more prone to brashly selling themselves and their achievements. Now it's hard to argue that the UK and US aren't closer in ethos.

But in Scandinavia it is a very different kettle of dried fish. There they have the Law of Jante, a way of describing the custom - which draws its modern name from a novel of 1933 by Danish-Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose - that forbids individuals emphasising their own success over that of the group.

"There is no question that it is invoked a great deal here," says Lars Tragardh, a historian born and based in Sweden, but who lived for several decades in the US. "People like to suggest it's part of the Nordic mentality.

"It has more to do with egalitarian ethos rather than a collectivist ethos. It is about not bragging or projecting yourself in a flamboyant way."

The Law of Jante normally comes into play when people are asked: "What do you do?"

"When I was in the States, starting a business in computer animation, I would be asked, 'What are you doing?' and answer, 'I have my own business'.

"There the reaction would be to view that as great. That's what you do - in some ways, the ultimate expression of self-confidence. In Sweden, the reaction would be much more suspicious. 'Do you think you are better than regular workers?' "

Another person with experience of the gulf in responses is US-born David Landes, editor of the Local, an English-language Swedish website, and resident in the country for 10 years.

Zlatan Ibrahimovic celebrates a goal for Sweden - but modestly

"'What do you do?' is one of the first questions in America. It isn't always at the top of the list in Sweden," he says.

Tragardh, a contributor to the Nordic Way paper delivered at the World Economic Forum in Davos, puts the mania for modesty down to Scandinavia's unique history.

"Kings were in alliance with a free peasantry. These cultures were profoundly egalitarian. They abhorred the claims of superiority that tended to be the hallmark of the aristocracy.

"The peasant communities had a distaste for flamboyant expressions of individuality, specialness or uniqueness." Thus the custom grew.

"You shouldn't believe you are more than you are. This attitude, in a way, we have in our social DNA," says Robert Mellberg, a tech entrepreneur behind social video site VideofyMe.

But in the modern Scandinavian business environment, attitudes are shifting, particularly among young people.

"It was our idea to create a homogenous population," says Mellberg. "Now we have a new generation and a post-industrial society. We are more capitalistic."

For those in the world of finance or in tech start-ups it doesn't do to be too circumspect about one's personal achievements.

"If you are in a situation where you are trying to sell a concept to a venture capitalist you best be persuasive that you are different and have a special idea that justifies a couple of millions of dollar of investment," says Tragardh.

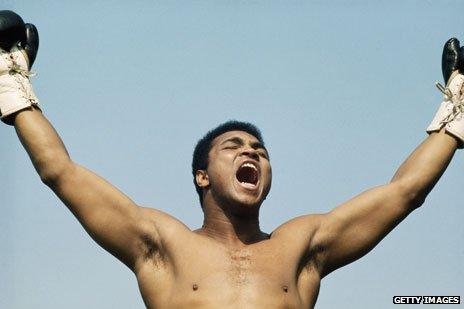

The Greatest? Muhammad Ali breaks the principle of Jante

The rise of Facebook and Twitter has also encouraged change in Scandinavia.

"Social media is about bragging," says Mellberg. "It is about telling people how brilliant you are through pictures and video."

The Law of Jante is a code of conduct to do with expression rather than an injunction against striving for success, notes Tragardh.

"It isn't about Swedes or Nordics not being competitive, nor is it about them being individualistic, which I would argue they are far more than Americans or Britons.

"The Nordic model is being celebrated. These are economies that are fiercely competitive and huge global successes."

But the tendency to be circumspect can make the reading of CVs a bit more nuanced, says Landes.

In reading through job applications, "Swedes are overly modest. They are almost ashamed of their accomplishments. You look at CVs and you can tell when it is an American or a Brit.

"It is different when someone works for a start-up and there is more of a go-getter attitude. If a Swede says something boastful it can be a more powerful thing as a result."

And even in the UK, the reasoning behind an individual doing the hard sell can be desperation as much as any fundamental cultural tilt towards bragging.

Claire McCartney, of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, says: "The economic climate, the difficult labour market makes people feel they have to sell themselves this way.

"In some roles, like sales, the gift of the gab is important. But people must be able to back their claims up."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external