Managing the Benghazi crisis is a tricky business

- Published

US officials are sworn in before congressional committee on Benghazi

Like his predecessors, President Obama is relying on a specially-commissioned report and efforts at transparency to control the fallout from Benghazi.

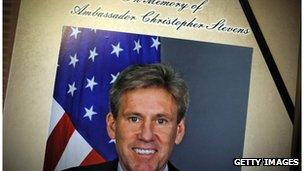

Ambassador J Christopher Stevens was trapped alone in a burning building in Benghazi. He and three other Americans were killed.

People were shocked. They also wanted to know what had happened, especially given the confusion in Washington in the aftermath of the attacks.

At first US officials avoided talking about al-Qaeda. Later they said that al-Qaeda had been involved.

Critics of the administration said that officials did not want to talk about terrorism before the presidential election.

White House officials went into crisis mode.

Less than two weeks after Stevens and the other Americans were killed, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said that a panel, headed up by former Under-Secretary of State Thomas Pickering, had been formed to investigate their deaths.

J Christopher Stevens was killed in Benghazi

US officials were following a well-worn path - when in trouble, announce the creation of a panel.

"These reports have become a standard way that governments manage crises," says Richard Gowan of New York University's Center on International Co-operation.

"There's always a sense that this is a way to remove the poison from an issue," Gowan says. "The problem is what comes afterwards."

When revelations about war crimes in Vietnam emerged, President Richard Nixon reportedly gave orders: "Get the Army off the front page."

His aides succeeded - in part by announcing investigations.

Officials told reporters they were looking into the atrocities - and could say nothing more. As a result journalists did not file pieces, at least not immediately.

During the George W Bush administration, more than a dozen investigations of Abu Ghraib and the treatment of detainees were announced.

These investigations ranged in quality. Some have been excellent, helping people to understand tragic, often horrifying events.

Yet many investigations have been politicised, conducted as a way to tamp down controversy rather than uncover evidence. Others have been limited in scope, diminishing their value.

Investigations of detainee abuse were launched during the Bush administration

The first investigation of Abu Ghraib, conducted by Maj Gen Antonio Taguba, for example, was restricted to military personnel.

Taguba did not look at the role of the CIA, leaving out an important part of the story.

A similar trend has emerged in the aftermath of Benghazi. Pickering's report appeared in December.

The report paid tribute to Stevens, "an exceptional practitioner of modern diplomacy", and assailed the state department for "systemic failures and leadership and management deficiencies".

Hillary Clinton served as secretary as state when Stevens was killed

Vali Nasr, a former state department adviser who is now the dean of Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, says the report is an exemplary "investigation of what went wrong".

Its purpose, says Nasr, is not "the witch hunt that the press wants - but to improve operations".

Not everyone agrees. Critics of the administration say that the report is politically biased.

There are other problems. Pickering and his co-authors decided not to ask Clinton about the Benghazi attacks, for example.

Pickering said they chose not to because they had already "questioned people who had attended meetings with her''.

In this way the report suffers from the same kinds of problems that that have plagued previous investigations commissioned during scandals.

The report's conclusions are, rightly or wrongly, dismissed as partisan. And without Clinton addressing Benghazi, its scope is limited - and consequently its authority is diminished.

Now Pickering has been subpoenaed by Darrell Issa, the head of the House Ways and Means Committee, to testify on the Republican representative's own terms.

Overall the investigation has done little to diminish the controversy.

On Wednesday White House officials tried again. They released a batch of emails - 100 pages.

The officials are hoping that people will read the emails and conclude that while presidential advisers may have made errors in judgment - by not talking about al-Qaeda in the early days, for example - they were not guided by partisan politics.

In the emails, officials compose "talking points" about Benghazi for a member of Congress.

The feeling of urgency is palpable in the emails. They also convey a sense of what life was like in Washington during the crisis.

Emails were hastily written - and also misfired.

"Sorry, sent to the wrong -," says one email that was composed on 14 September.

The style of the emails is familiar to Suzanne Nossel, who served as a deputy assistant secretary of state during the Obama administration.

Nossel recalls one crisis as she and her colleagues tried to sort out a strategy.

"There was someone who had to sign off on something, but it was 2am," she said. "You don't even know if someone is awake."

"At what point do you just quit?" she says. "The place where it comes to a rest can be just as much a matter of time as a matter of people coming together in agreement."

Shamila Chaudhary, who served as director for Afghanistan and Pakistan on President Obama's National Security Council, recalls, "Every single word that you write means something."

"But when people write emails, it's different," Chaudhary says. "And when you are in a crisis, forget all that."

A Libyan security guard carries flowers for Stevens

The release of the emails, as well as the announcement of the panel, were attempts to manage a crisis.

But these efforts have limits.

"They are frequently more about buying time than about actually getting to the bottom of what happened," Gowan says.

People who have been on the inside agree with Gowan's assessment.

Matt Latimer, who served as a speechwriter during the Bush administration, recalls a tense meeting with the president and his advisers during the US financial crisis.

"There were a lot of terms that nobody understood and for no reason he put this Mickey Mouse hat on his head," Latimer says, describing the president.

"He was either saying, 'We're running a Mickey Mouse operation or we're in fantasy land'," Latimer says. "I wasn't sure which one was right."

One thing was clear, however. Crisis management is a mixture of earnestness and absurdity - and is an integral part of working in the White House.