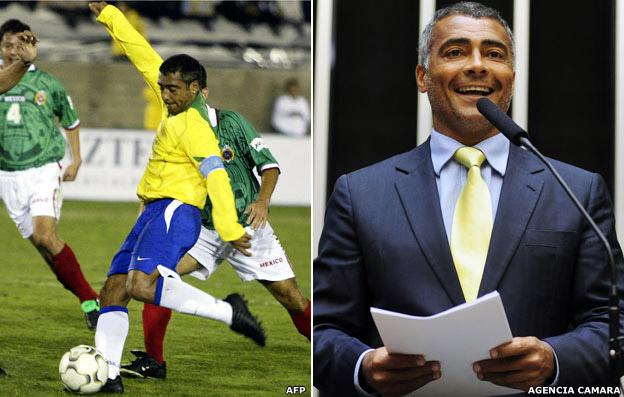

Romario: From football rebel to politician

- Published

It is one of the more improbable character re-inventions. One of the greatest Brazilian footballers, a rebel rarely out of trouble, reborn as a hard-working politician and a campaigner for disability rights. The BBC's Tim Franks went to Rio de Janeiro to see it with his own eyes.

This is a man who built his reputation as one of Brazil's footballing gods, a goal-scorer par excellence, the master opportunist. His stocky, 165cm-frame won his country the 1994 World Cup. He scored 1,000 goals in his 20-year career.

And off the field he was almost as productive - at least for headline-writers. He was the archetypal celebrity bad boy, a font of reckless, feckless, macho bravura.

And now he has remoulded himself into a serious national politician. The question has to be - Is Romario for real?

My first encounter with Romario de Souza Faria was in the life-drainingly dull confines of Committee Room Number Four of the Federal Parliament in Brasilia.

I had been invited to witness him in his role as president of the congressional committee on sports and tourism. Duly, Romario strode in to the room, wearing the smartest suit and tie by some distance.

The session had been billed as a grilling of Sports Minister Aldo Rebelo in the run-up to next year's staging of the World Cup by Brazil. There are indeed some serious questions to be asked, but this was no inquisition.

The Brazilian parliamentary style, it appeared, was instead to take grandstanding verbosity to new, oxygen-starved heights. Come the fourth droning hour, my chin began to sink towards my chest. Romario, in contrast, was bouncing - literally bouncing - in his chairman's chair.

Occasionally, a lizard's tongue would flick around his mouth. From time to time, with a wave of his hand and a glance, he would summon a young female attendant to bring papers or impart a message.

Eventually, the unthinkable happened, and the congressmen ran out of things to say. Romario left the committee room and began the walk to his office, a walk slowed by the queue of fellow MPs and parliamentary officials hailing this former footballing deity, squeezing his hand and inviting him to gurn at camera phones.

Romario and his daughter, Ivy

Some time later, squeezed behind his desk, in his small parliamentary office, Romario explained how the date of his conversion from sporting tyro to public servant could be traced to a precise event. The birth of his sixth child, Ivy.

"When I stopped being a football player, it's true that politics didn't even enter my head," Romario conceded. "Then eight years ago my daughter was born with Downs Syndrome.

"I started spending time with parents, relatives and friends of people who have some kind of disability. I began to realise there was no-one to represent these people in politics, so I decided to stand for election."

It is clearly a story which Romario has told many times before. And he is a campaigner for the disabled - the majority of his questions to the minister in the select committee were about disabled access to the World Cup matches. If Brazil 2014 falls short on facilities for wheelchair users, it won't be for lack of effort on Romario's part to hold organisers to account.

The confounding aspect to his change, though, appears to be his diligence. This was a man renowned for announcing to a series of club managers that he didn't need to train. He just needed to turn up and score. And yet in the Brazilian parliament, 900km from his home city of Rio, Romario has one of the best attendance records of any MP.

Romario, again, seems to have his answer ready - he is paid by the public now, rather than by a private company. So he has to do the hours.

The BBC's South American football correspondent, Tim Vickery, wonders whether there is not also a subconscious urge to compensate. He recalls Romario's distress at picking up an injury before the 1998 World Cup - a tournament "which could have been his definitive statement as a footballer".

From then on, says Vickery, Romario embarked on the "pointless statistical accumulation" of trying to reach the 1,000-goal milestone. "There's no doubt about it, he's putting his back in" to being a politician.

"But I wonder if part of this is a desire to make his mark based on a belated recognition that he could've made his mark even more on the football field."

And Romario certainly is making his mark, laying into his country's preparations for hosting the 2014 World Cup. His tie remains square, his shirt uncreased, his expression unchanged, but his language coarsens. Brazil, he says, "has opened its legs" to Fifa, football's world governing body.

The Socialist MP's ire has been pricked, in part, by the billions shovelled into building gleaming new stadia and the surrounding infrastructure for a World Cup - a charter for waste and corruption, he says, and for private profit over public good.

But the level gaze of his deep brown eyes has also turned not just on what is being done, but who is doing it.

He has long disparaged the men who run the Brazilian Football Federation, the CBF. Last year, he was part of the campaign which led to the then CBF boss, Ricardo Teixeira, stepping down over revelations that he'd accepted kickbacks.

Teixeira, Romario tells me in his typically abrasive style, was "a cancer". But the new boss, Jose Maria Marin, he says, is even worse.

Marin was a state congressman during the 20-year period that Brazil was under military dictatorship. In 1975, at the Sao Paolo congress, Marin denounced TV Cultura for its left-wing leanings.

TV Cultura was run at the time by a former BBC journalist, Vladimir Herzog. Herzog was summoned for interrogation by the secret police. When he turned up, he was tortured, and died.

The following year, Marin gave a further speech in Congress praising the work of the chief of the secret police, under whose watch thousands had been rounded up and tortured.

Romario says he is all in favour of leaving the past behind, "but the people who took part in the dictatorship should be left behind too". To have Marin preside over the World Cup, he says, would be a "disaster".

Marin has his supporters, who are, in turn, Romario's critics. The suave 72-year-old senator, Nelson Marquezelli, says that for as long as he has been in politics, for 50 years, he has been a friend of Jose Maria Marin. And the inexperienced Romario is, he says with acerbic condescension, "off-target… just as he often was on the pitch".

"It's not true that a speech made by one congressman could make a journalist, who was as famous as Vladimir Herzog was at the time, go to prison," he says.

"Marin's speech had no influence over this. At the time Jose Maria Marin was not an important congressman in the Brazilian political establishment."

Marquezelli says Romario is fuelled more with a desire to settle scores than out of any great principle. It is clear, at least, that Romario is ambitious - in an aside, at the end of our interview, he tells me that he doesn't want to run the CBF, yet. Maybe in "five, six years".

If that were ever to happen, it would be another remarkable step for Romario away from his humble beginnings, in one of Rio's favelas, or shanty towns.

How far he has already travelled is clear on a warm Saturday morning, as I am permitted to watch him and his chums playing futevolley, the football equivalent of beach volleyball, on the sand, opposite his apartment on a very swanky stretch of Rio coastline. His young PR-aide, Marcia, tells me I can watch. But I can't talk.

Despite promises that I'll have a further extensive interview, and get to meet his daughter Ivy, Romario has changed his mind. "What can I say," Marcia grins. "He's temperamental." (Marcia has already confessed that she is in her dream job, having spent her teenage years gazing at posters of Romario on her bedroom wall.)

But, she promises me, you'll see him tomorrow, when he attends a function in a favela.

Jardim America ("America Garden") has an unlikely name. It is one of Rio's poorest favelas. It has not, in the jargon of the Rio police, been "pacified", ahead of next year's World Cup.

When I arrive on the Sunday, my driver has to dismantle a makeshift roadblock, erected by a gang. When we have parked, he wanders off for a coffee. He quickly returns, without a coffee, having seen, round the corner, members of the gang lounging on the street, openly tooled up with guns.

We are there because Romario is due to be the guest of honour at the official opening of an artificial football pitch. It is the first municipal project which this impoverished, dishevelled district has had in a full 15 years. It came about, in part, because Romario had pushed the local council to build it.

Next to the pitch, a large group of young boys are waiting. Their T-shirts are torn, some are incongruously wearing just one sock. But most have gaudy football boots.

They are playing an energetic game on the broken concrete, their ball a bottle top. Behind them, large men fiddle with the sound system, as a poster thanking Romario flaps and strains in the wind.

Romario enjoys playing futevolley on the beach opposite his apartment in Rio

Two hours after the appointed time, the numbers have swelled. Romario's staffers have long since handed out hundreds of expensively produced freesheets pumping Romario's list of achievements as an MP.

And then, at last, our long-suffering local producer, Julien, receives a text from Marcia. Romario is not coming, after all. His reason - it is raining, and so the traffic will be bad.

It was, in fact, barely spitting. And the roads that Sunday had been the clearest we had seen all week.

The people of Jardim America still held their small ceremony, inaugurating the new football pitch. The boys, whose faces had fallen at the news that Romario wasn't coming, poured on to the astroturf for a chaotic game involving several balls.

Romario himself had, back in parliament, conceded to us he wasn't perfect.

In one respect, though, he is determined not to sink to the level of some of his fellow MPs.

"What I have in my conscience is that while I'm here in Congress, I won't be corrupted, I will do justice to the people who voted for me."

And the people of Jardim America will probably vote for him again en masse at the next election.

What really motivates Romario may remain a riddle. He may still have a deep streak of self-centredness, of - as football writer Tim Vickery puts it - the "malandro", the stereotypical Rio wideboy, "who only does what he wants, and all that he wants".

But is Romario making an impression in politics? There can be no argument there.

Romario Tackles Brazil is broadcast on BBC News Channel on Saturday, 18 May and on BBC World News on Saturday 18 and Sunday, 19 May.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external