A Point of View: Tom Ripley and the meaning of evil

- Published

Patricia Highsmith's Ripley novels are classics of crime literature. The author's view of evil - as expressed through the amoral title character - fascinates writer and philosopher John Gray.

(Spoiler alert: Key plot details revealed below)

We all think we know what evil means, and there are many who believe - despite what we hear on the news every day - that evil is gradually diminishing in the world as human beings become more reasonable.

Patricia Highsmith thought differently. She's seen by most people as a writer of thrillers, and there's no doubt that she's a consummate practitioner of the genre. For me she's also one of the great 20th Century writers, with a deep insight into the fragility of morality.

From her first novel, Strangers on a Train, which Alfred Hitchcock adapted for the screen in 1951, and throughout her writing life, Highsmith was always fascinated by evil.

At times it's hard to resist the feeling that she actually admired evil - an impression reinforced by her attitude to her best-known character, the enigmatic murderer Tom Ripley. When she was beginning the first of the five Ripley novels, Highsmith wrote that she was "showing the unequivocal triumph of evil over good, and rejoicing in it. I shall make my readers rejoice in it, too".

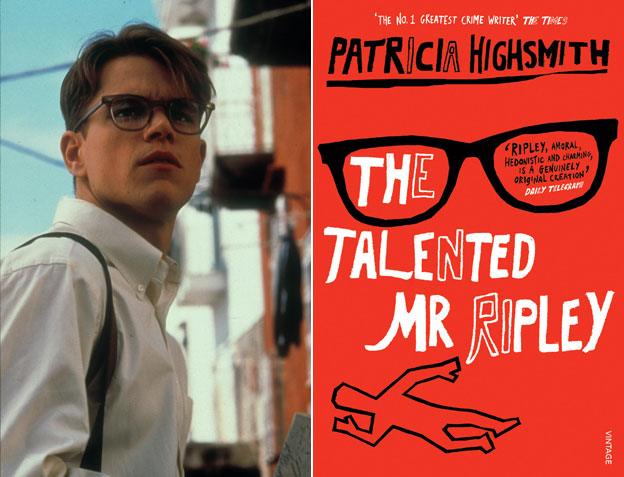

Published in 1955 under the title The Talented Mr Ripley, the book was written very quickly. "It felt like Ripley was writing it," she said. Her biographer tells us that for a time Highsmith identified with the character she had created, signing herself in a letter to a friend, "Pat H, alias Ripley".

The Ripley novels have been read as Highsmith meant them to be read - as depictions of the triumph of evil - and many have found them disturbing for that reason.

But there's nothing in what she tells us of him that suggests Ripley thinks of himself as evil. Instead he lives on the basis that good and evil have no meaning. It may have been this aspect of Ripley that Highsmith identified with most strongly. Often unhappy and angry at humanity, she may have envied the carefree amorality of her fictional alter ego. Yet it's this indifference to morality that makes the character of Ripley so disturbing to her readers - and, I believe, so instructive.

When Ripley begins his career as a criminal by killing and impersonating a rich young man, it's because the life he acquires in this way - with its leisurely days and apartments filled with exquisite furniture - is more attractive than the one he had before. When he goes on to kill one of the young man's friends, it's because the friend is becoming suspicious. Later, when Ripley is making a living from art forgery, he kills in order to prevent his crimes from being exposed.

Ripley finds a certain satisfaction in despatching his victims, but it doesn't come from any dark romance of evil. It's the satisfaction that comes with a job well done. He kills when killing is necessary in order to maintain the kind of life he enjoys, not because he enjoys murdering people.

Ripley has often been described by critics as a psychopath, but Highsmith believed he wasn't so different from the rest of humanity.

"The psychopath," she writes in her notebook, "is an average man living more clearly than the world permits him." In becoming a criminal, she believed, Ripley was living more lucidly and more purposefully than most human beings are capable of doing.

In the later novels he's shown happily married to a charming heiress and living in a fine chateau on an estate in the French countryside. Neither Ripley's wife Heloise nor her wealthy family are interested in how his money is made. They don't care as long as their semi-aristocratic lifestyle runs on smoothly.

Ripley doesn't condemn them for this indifference. It makes for an agreeable arrangement, enabling him - always an aesthete - to spend his time learning to play the harpsichord and gardening in the chateau's spacious grounds.

Yet there's more than a hint of contempt in him for the high society in which he moves. So long as it can maintain the pretence of innocence, it's happy to benefit from his criminal activities. He has chosen a life of crime in full awareness of what it involves, and takes a certain pride in the fact.

Ripley has been compared with Raskolnikov in Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, and there is some similarity. Both choose to commit murder for the sake of goals they think are more important than traditional moral values. That's where the likeness ends, however. It's not just that Ripley gets away with his crimes, while Dostoevsky's murderer confesses and is punished. Ripley shows no trace of remorse for what he has done. Having killed, he carries on calmly with his life.

As he says to a young man who has come to him for help after having killed his own father, "You either let some event ruin your life or not. The decision is yours." Again, Raskolnikov justifies his crime on the ground that he can use the proceeds to promote a better life for others. Ripley sees no need to justify his actions in moral terms.

The contrast between Dostoevsky's moralising murderer and the amoral Ripley reflects a fundamental difference in world-view. Raskolnikov still lives in a universe shaped by religious ideas of good and evil. When he trembles before killing an old woman for her money, it's because he's been taught that human life is intrinsically precious.

John Simm as Raskolnikov in a BBC adaptation of Crime And Punishment

For Ripley, on the other hand, nothing is precious in this way, and nothing is intrinsically evil. He has a code of values. He admires energetic, resourceful people and disdains those who are conformist and mean-spirited. He cherishes beauty and loathes ugliness. He's capable of sympathy and kindness. He becomes genuinely fond of the young man who comes to him for help. He sees no evil in what the young man has done.

In Ripley's world there's no such thing as evil. For him, no longer living in the moral universe inherited from religion, evil is just a relic of superstition.

Like Highsmith, Ripley is a thoroughly secular figure. She was an unflinching atheist who felt only contempt for religion. In contrast to most atheists, she didn't believe morality is deeply rooted in human nature.

It's not just that people set morality aside as a matter of self-interest. Human needs and impulses are tangled and conflicted. Moved by their passions, people often destroy the good in others and at the same time sabotage their own. Curiously, it's a view of human frailty that Highsmith shared with the religion she despised.

For many who reject religion today, what's generally viewed as evil is ultimately a kind of error, a product of ignorance and lack of understanding. As knowledge grows and people become more rational, they will become kinder and more considerate in their treatment of one another. Rightly, Highsmith could never bring herself to take this high-minded view of things seriously.

After all, Ripley isn't ignorant or irrational. He's a cultivated, knowledgeable human being. Certainly, his indifference to morality is shocking. But this isn't the result of any kind of intellectual confusion. If anything, Ripley is more rational than most people, and he's acutely attuned to human emotions and motivations.

But rather than leading him to be more moral, these attributes go with a terrifying detachment from morality. While he's capable of feeling human sympathy, he's equally capable of coolly committing murder. What's chilling in Ripley isn't the picture of evil so many people have seen in him. It's the picture of a human being who lacks the very idea of evil.

Secular thinkers imagine that religion can be dropped like belief in fairies, while morality continues much as it did in the past. If people behave differently in a post-religious world, it can only be an improvement. Morality itself won't radically change.

More rigorous in her unbelief and more sceptical of human goodness, Highsmith saw things more clearly. Giving up the moral outlook inherited from religion means a vast transformation. A world without the idea of evil might in some ways be a better world, but it would be different from any we've ever lived in - and from any that high-minded believers in humanity could imagine.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external