Champions League final: Is fussball coming home?

- Published

With Borussia Dortmund playing Bayern Munich in the Champions League final on Saturday, thousands of German fans will be heading to the home of English football, Wembley. But is it also the home of German football?

"Fussball is coming home" ran the headline in the Bavarian-based Sueddeutsche Zeitung early in May, as Bayern Munich beat Barcelona to set up a Wembley final against Borussia Dortmund

It will all leave Karl Planck turning in his grave.

In the 1890s, this German gymnast and patriotic teacher raged against the "foot-louts" in Germany suffering from what was called "the English disease".

They were playing a new game, football, imported from Britain. The sport was, Planck wrote, "absurd, ugly and perverted".

Planck hoped that Germans would stick to gymnastics, seen as better at producing young men fit for military service.

But the thousands of today's Germans heading for Wembley Saturday will prove that Planck failed and British sport triumphed.

Such was British influence in 19th Century Germany that all kinds of sports were imported, ranging from tennis to cricket (14 teams in Berlin alone by 1914).

.jpg)

Tourists aside, few people play cricket in modern Germany

It was football that gained mass popularity, encouraged by British coaches and Germans inspired by the way the British played.

Many early German teams paid homage to football's home country with names like Britannia Berlin.

But as the game gained approval from the German establishment, the names became more nationalist.

The Kaiser pointedly supported Germania Berlin. And the Borussia in Dortmund is the Latin name for Prussia - though the team is said to have been named after the local Borussia brewery.

World War I halted - for a while at least - any sporting fellow-feeling between Britain and Germany, though there were poignant stories of soldiers playing football in no-man's land during Christmas truces on the Western Front.

As international football developed after World War II, so did a famous national rivalry between England and Germany.

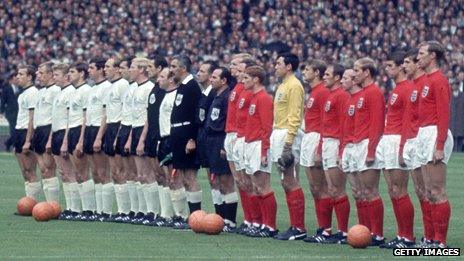

England's belief in its top footballing status was revived by victory in the 1966 World cup final against West Germany at Wembley.

But a European Championship defeat at the same stadium in 1972 confirmed, as the German coach Helmut Schoen put it, that England "seemed to have stood still in time" while the Germans were now "far superior technically".

England have rarely had the upper hand since 1966

Football now symbolised a sense among Britons that their country was indeed falling behind the Germans technically and economically. German footballers, like German workers, were seen (in cliched sports reporting at least) as exceptionally disciplined and organised.

But Uli Hesse, author of Tor! The Story of German Football, told me German admiration of English club football was still evident in the 1970s and '80s.

German fans waved Union flags at their club matches and wished their grounds were more like English ones.

Can English football learn from the Germans?

Only more recently, he adds, has the commercialisation of the British game changed that. Now, in many ways, "the English want to be more like the Germans".

Just as many British politicians admire the way German industry is run, with long-term ownership, workers enjoying seats on the board and hugely successful exports, now British football fans are casting envious eyes towards German clubs.

Fans have more influence, foreign owners are kept at bay and ticket prices in atmospheric grounds are lower.

And coverage of German football in the British press has certainly changed, with fewer traditional references to tin helmets and blitzing.

The Sun has written of Wembley preparing this weekend for "the great invasion of our Anglo-Saxon cousins".

So could this Wembley event, at which the Football Association marks its 150th anniversary, also remind everyone how football unites England and Germany?

Football diplomacy, or lack thereof

The politicians might approve. German Chancellor Angela Merkel, a conspicuous football fan since Germany hosted the 2006 World Cup, is said to be very keen to keep Britain in the EU. Could footballing ties help?

Royalty could also play its role. While Prince Charles may be more interested in polo, his sons enjoy football.

The Duke of Cambridge, a regular Wembley spectator, is president of the Football Association - encouraged no doubt by the key royal PR adviser, Paddy Harverson, who was recruited directly from Manchester United.

Next year, the royals might like to remind us, marks 300 years since the Hanoverians succeeded to the British throne in 1714.

The Royal Family changed its name during the First World War from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor, just when German football teams were busy shedding their English-sounding names.

But echoes of that close Anglo-German relationship remain. There are players too who symbolise this footballing relationship.

Bert Trautmann and the diving save that broke his neck

Bert Trautmann was a former prisoner of war who played on heroically for Manchester City in the FA Cup final at Wembley in 1956 after suffering a broken neck.

He later created a foundation to promote Anglo-German understanding through football.

And Lewis Holtby, current member of the German national team and a Tottenham Hotspur player, is the son of a German mother and an English father who was stationed in Germany with the RAF.

So there is a real sense of German football returning to a kind of home as thousands of Dortmund and Bayern fans head for Wembley.

Meanwhile, the millions of English fans watching on TV can at least enjoy one game in which a penalty shootout involving German footballers will not lead to terrible Anglo angst.

As they contemplate the success of German club football, and the global strength of the German economy, they can console themselves with the thought that there is one British export still proving permanently successful: Fussball.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external