Why so few storm shelters in Tornado Alley hotspot?

- Published

Oklahomans had only limited access to safe rooms and shelters during the storm. People who live in Tornado Alley explain why.

Representative Pat Ownbey was hunkered down in a basement of the Oklahoma House of Representatives as the tornado arrived in the Oklahoma City suburb of Moore.

Ownbey had been through a milder episode before. A tornado hit part of his district in 2009, destroying a mobile-home park.

It turned the neighbourhood into "a landfill", he says.

Afterwards Ownbey tried to get a bill passed that would require mobile-home parks to offer emergency plans to residents.

He also looked into building a shelter for his house - but never got around to it.

"It's risk versus cost," says Ownbey. "You think it's not going to happen again."

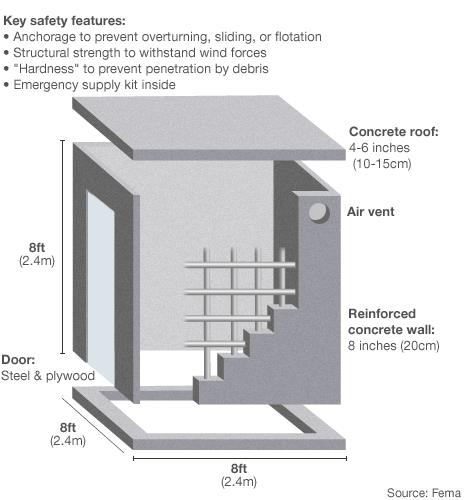

Storm shelter design

Yesterday, though, it did. His wife, daughter, son-in-law and 18-month-old grandson were at his house, a sand-coloured, brick three-bedroom property, in Moore.

As the tornado tore through their neighbourhood, Ownbey watched on television. He was shocked - and forgot that he had once wanted to build a shelter.

"At the time I was just praying," he says, talking on a mobile phone in his Jeep Grand Cherokee, a relatively storm-worthy vehicle, as he drives back from Moore.

The tornado missed his house - but killed more than 24 people.

Some may wonder why Ownbey and so many others who live in Tornado Alley, as this part of the country is known, do not build storm shelters.

By his own account, Ownbey embodies many of the reasons for this omission.

He cites both personal and political arguments for living in a house that does not have a place to hide during a storm - and in a state that devotes only limited resources to shelters.

As Ownbey points out, shelters for private homes are expensive - $3,000 to $5,000 (£2,000 to £3,300). At the state level, they cost even more.

He and many others do not believe that the government should invest its money in community storm shelters.

Their views may seem odd to people outside of the region.

Midwesterners are known for their rugged individualism and pioneer spirit.

This hardy streak means that many people in the Midwest are suspicious of outside help - and of government intervention.

They think that people should take care of things on their own.

"It's easy to say the government should build shelters for everybody," explains Ownbey. "But in the end you can't have the government providing everything to everybody."

"There is a risk to life itself."

Setting aside ideological reasons, building a shelter is a hassle. Oklahoma earth can be hard to dig into - much of it is clay.

Still shelters can be built in yards, anchored to a concrete slab. though experts say above-ground ones may not have survived this storm.

As it turns out, however, the city of Moore has no public tornado shelters, as its website makes clear, external.

"There's nowhere you can go," says an official who works for the city's Community Development Department.

There are, however, safe rooms, cellars and places in private homes where people can seek refuge.

"There are over 3,000 of them," says the city official, who wishes to remain anonymous. About 55,000 people live in Moore.

As people in Moore discovered after a May 1999 tornado that killed dozens of people, the shelters work.

A researcher said that the units survived, external - and so did the people hiding inside of them.

Some government money has been provided to people to build safe rooms in Oklahoma over the past several years.

These individuals received support from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (Fema) through a programme known as SoonerSafe.

For those who were selected for the scheme, the federal agency paid for 75% of the cost of building a shelter.

A state programme, Operation Safe Room, also provided funds for people in Oklahoma who wanted to build shelters.

Altogether more than 10,000 shelters have been built in Oklahoma with the support of the government, according to a June 2011 article in the Journal Record Legislative Report, an Oklahoma City-based business and legal newspaper.

In other parts of Oklahoma, there are 382 federally funded safe rooms or shelters that are available to the public, according to a Fema spokesperson.

Hundreds of these facilities are located throughout Tornado Ally. Three states, Arkansas, Missouri and Kansas, have more than 150 of the public shelters, and Texas has 49.

Yet those who have seen a tornado do not necessarily invest in a bunker.

"It's the afterthought," says Jeremy Davis, the owner of Twister Safe, a Missouri-based firm that builds storm shelters.

"It's, 'Well, it hit. It probably won't hit again,'" says Davis.

"But it's the kind of thing that when you need it, you need it."

Still a decision can be made late.

Dirk DeRose, the owner of New Day Tornado Shelters, a company that is based in Tulsa, says that people turned to him yesterday while the storm was brewing.

DeRose, who used to work as an aircraft structural technician, says that he had gotten lost on a gravel road and stopped to ask for directions at a mobile home.

He was outside of Big Cabin, a town that is roughly 50 miles (80km) from Tulsa.

The person in the mobile home saw construction materials in his truck - and asked if he could build a shelter for his family.

DeRose built a safe room in an hour.

"There's no safe place inside a mobile home," DeRose says. "Now these people have one."

One Israel-based blogger, Laura Rosbrow, says that she cannot understand why people in Oklahoma do not have more publicly-funded shelters.

In Israel, Rosbrow says, bomb shelters are located "within blocks of every residence".

"In Israel, you feel like the country is giving you peace of mind," writes Rosbrow on her blog, external. "Isn't that the way it should be?"

In contrast Ownbey believes that the decision to build a shelter should be market driven - and not guided by the government.

Yet he admits that individuals do not always make a prudent choice. Years ago he did not build a shelter. He will now, though.

"The second time - I think it's time to put it in," says Ownbey.