Which is the North's best building?

- Published

The North of England has great football, but culture? Forget any stereotypes you have and think again. The 21st Century has brought the North some cultural buildings that help redefine world architecture, writes Martin Goodman, professor of creative writing at the University of Hull.

Antony Gormley's vast Angel of the North, erected on a hill above an old mineshaft near Gateshead in 1998, gave notice that change was coming.

George Gill, a former miner and leader of Gateshead City Council, knocked on all the neighbourhood doors.

Did people want this giant sculpture as a neighbour?

Most of the funding would come from the National Lottery.

"Bring it on," the people said.

With its arms stretched wide like shipyard cranes, Gormley's iron angel stares at the horizon as motorways and trains speed people past. Now people stop.

From the train at Newcastle they descend to the Tyne, where the elegant Gateshead Millennium Bridge leads them over the river.

To their left is the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, an "arts factory" built into the high brick rise of a converted granary.

To their right, above a flight of steps, the bulbous waves of three linked glass domes trace the shape of the Tyne Bridge's arch against the sky.

This is the Sir Norman Foster designed Sage Gateshead, a trio of linked concert halls.

The Northern Sinfonia is resident in this world-class venue, while jazz students, folk singers, disabled people, retirees and all manner of folk come to the honeycomb of studios in the lower level and make music of their own.

Others come to this atrium of curved glass for coffee and an indoor stroll. They are protected from the weather as they look out above the river.

Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima) has views of the North York Moors

One striking aspect of the North's new iconic buildings is the way they have opened up the cities' rivers.

These riversides were once closed off as shipyards. New cultural buildings tempt the people back.

All these new buildings major on vistas.

The plate-glass frontage of the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima) is crossed by the startling gash of its internal staircase.

Those stairs lead to an outdoor space with views of the North York Moors.

Inside, galleries of blond wood meld the permanent art collection with visiting exhibits.

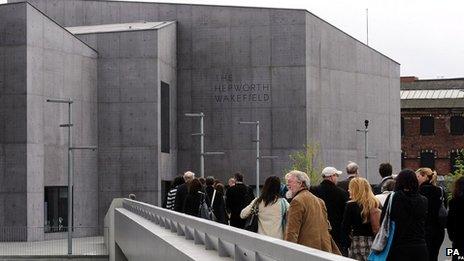

The Hepworth Gallery in Wakefield is named after local sculptor Barbara Hepworth

Hull chose fish rather than art, but like Gateshead it has used iconic architecture to open up its rivers.

The architect Sir Terry Farrell sited The Deep at the confluence of the Humber and the river Hull, a tributary which gives the city its name.

It juts above the waters like a geological shard, a statement of intense visual intent that already stands as an icon for the city.

The landscape around here is flat. Climb up into the nose cone of the building and you find that the building has given Hull's citizens a new view.

In one direction is the Humber Bridge; in another the Humber sweeps in from the sea; and a new bridge connects this building to the Old Town, dominated by the 14th Century tower of Holy Trinity Church.

The Deep is an iconic building but its unique selling point is fish, rather than art

The intention is to attract visitors across that new bridge to the city's existing gallery and museum quarter.

The Deep brings in a steady 300,000 visitors a year to its aquarium.

It is about to add penguins to keep the people coming.

Wakefield brought in an astonishing first-year total of 500,000 visitors to its Hepworth Gallery with high art alone.

The river Calder powers against the Hepworth's foundations, which rise into a sequence of polished concrete cubes.

In the gallery spaces designed by Sir David Chipperfield, a play of natural light colours the sculptures of Wakefield-born Barbara Hepworth.

The Gateshead Millennium Bridge can be raised so boats can pass beneath it

Abandoned red brick warehouses still line up alongside the Hepworth. New buildings can spark regeneration but it takes time.

The turn of the millennium was a golden period for funding.

Lottery money was later diverted to the London Olympics but Liverpool somehow managed to pull together the public finance to open the Museum of Liverpool in 2011.

Previous developments, including a branch of the Tate, were built into the old structures of the Albert Dock.

But the bold white sweep of the Museum of Liverpool is a radical statement of the new.

It drew more than a million visitors in its first year, all keen to tour its levels and discover how Liverpool is telling its own story.

The Museum of Liverpool (far left) attracted a million visitors in its first year

In London visitors queue to pay £25 for a view from the top of the Shard.

For a human at the pinnacle of that iconic yet commercial building, the city sinks into anonymity.

From the Museum of Liverpool the views across the Mersey are free.

People who buy lottery tickets have dreams of great riches.

A percentage of those lottery purchases have funded these new buildings of the North, so those dreams have come curiously true.

This is rich iconic architecture but these buildings go way beyond bold gestures. They are thronged, and are coming to be loved.

You can follow Martin Goodman on Twitter @MartinGoodman2

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external