Did The Rite of Spring really spark a riot?

- Published

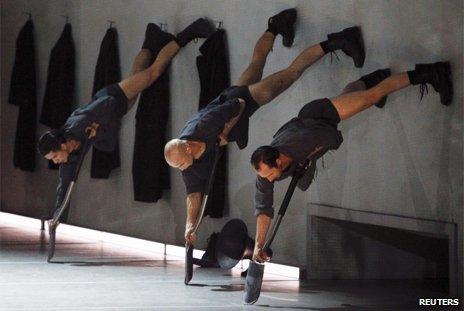

Finnish National Ballet's 2013 revival of the original 1913 production

Of all the scandals of the history of art, none is so scandalous as the one that took place on the evening of 29 May 1913 in Paris at the premiere of Stravinsky's ballet The Rite of Spring.

The Rite descended into a riot, the story goes. Magnified in the retelling, it has acquired the unquestionable certainty that only legend can have. Everyone simply "knows" that there was a riot.

But is it possible to separate fact from fiction?

Was there violence?

Dozens of witnesses left accounts of the evening, but they tend to say different things. According to some, blows were exchanged, objects were thrown at the stage, and at least one person was challenged to a duel.

There is no doubt that there was a lot of noise - contemporary press reports make this clear. Esteban Buch, director of studies at the School of Advanced Studies in Social Science in Paris, says it's difficult to deny that "something really extraordinary" took place - but he points out that if you look at the accounts given over the months, years and decades that followed, "the riot" acquires greater importance as time goes on.

The Rite and the riot become entangled in memory making this event, as he puts it, "some kind of gate to modernism, to the 20th Century".

Choreographer and dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, left, in the original Rite of Spring

How soon did the trouble start?

Lydia Sokolova, one of the dancers on the stage that night, said the audience came prepared.

"They had got themselves all ready. They didn't even let the music be played for the overture. As soon as it was known that the conductor was there, the uproar began," she said in an interview recorded in 1965.

There had been some noise two weeks earlier at the premiere of Debussy's ballet, Jeux, and critics had heaped abuse on Vaslav Nijinsky's choreography. Now Nijinsky had choreographed the Rite of Spring - rumoured to be the last word in Russian primitivism or modernist chic, depending who you believed. So part of the audience may well have been predisposed to be outraged.

"There was an existing tremor in the air against Nijinsky before any curtain went up," says Stephen Walsh, professor of music at Cardiff University. Others say the trouble began with the start of the overture and its strangled bassoon melody, and other strange sounds never before conjured from an orchestra.

Igor Stravinsky, for his part, said the storm only really broke after the overture, "when the curtain opened on the group of knock-kneed and long-braided Lolitas jumping up and down".

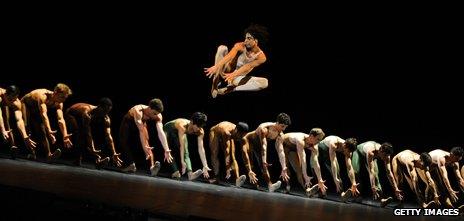

Kenneth MacMillan's The Rite of Spring from Beyond Ballet Russes, 2012

Were the police called?

It's hard to say at this point what role the police played, if any. One account has it that about 40 people were arrested, which would suggest police arriving in large numbers.

An extract of a recent recording of the Rite of Spring

Another witness points out that it was standard practice for some police to be present at Parisian theatres at the time. Esteban Buch visited the Paris prefecture archives to check police records, only to find that the relevant file was missing. His hunch is that there were a couple of policemen in the theatre as a matter of routine "and they just witnessed the scene without doing much".

Was it class warfare?

The brand new Theatre of the Champs Elysees was "awash with diamonds and furs" according to one contemporary report. It seems that the beau monde really did turn out for this premiere - and some will have been keener than others on the avant-garde performance. Jean Cocteau wrote that "the aesthetic crowd... would applaud novelty simply to show their contempt for the people in the boxes".

But were they divided by class? Buch says there are unlikely to have been any poor or even middle class people in the auditorium.

"My reading of the evidence is that actually the divisions went inside social groups - you have people who are very much alike and they have different opinions on the piece." One barrier to understanding the quarrel, Buch adds, is that none of those who protested ever left a record explaining the reason for their anger.

A modern staging to mark the centenary at Moscow's Bolshoi Theatre

Was it the music or the dance that shocked?

The young Stravinsky had taken Paris by storm in previous seasons. His Petrushka, the year before, had been a massive hit. "There is no question at all, he was a star," says Walsh. But compared with the Rite of Spring, "Petrushka was not such a forbidding score, by any means."

Stravinsky himself said that when he first played the beginning of the Rite, with its dissonant chords and pulsating rhythm, to Serge Diaghilev, the founder of the Ballets Russes, Diaghilev asked him a "very offending" question: "Will it last a very long time this way?" (Stravinsky replied: "To the end, my dear.")

So the music was as startling as the strange jerky movements of the choreography. Esteban Buch argues that you cannot separate the impact of one from the other. What upset people, he thinks, was "the very notion of primitive society being shown on stage".

And another centenary take by Bejart Ballet

Did Diaghilev want a scandal?

"He knew there was going to be trouble," said Lydia Sokolova, and there are some signs that he was hoping for a scandal.

Announcing the Rite of Spring in the Parisian press, Diaghilev had suggested it would cause "impassioned debate". In so doing, Esteban Buch suggests, he was setting the scene "for maybe not a riot, but at least a controversy". He certainly got one.

Walsh points out the curious fact that the dress rehearsal passed off "without a murmur", whereas with Debussy's opera Pelleas and Melisande a decade earlier, there had been trouble at the dress rehearsal but not at the premiere. So perhaps chance also played a part.

Was the premiere a success?

The performance continued to the end, despite the rowdiness of the audience, and one thing most accounts seem to agree on is that there was an ovation.

Walsh cites one press report, however, which suggests that when Stravinsky and Nijinsky took their bow, the ovation fought against the noise of protesters.

As he puts it, this does "slightly modify the impression that they stood in front of the curtain and were greeted with uniform admiration".

So even on this point, we cannot be quite sure.

Ivan Hewett explored the myths that surround the infamous first performance of the Rite of Spring in I Predict a Riot on BBC Radio 3. Catch up with iPlayer.