Why does France insist school pupils master philosophy?

- Published

I have been staring in admiration over the shoulder of my 17-year-old daughter, as she embarks on a last mental rehearsal before a much-dreaded philosophy exam.

My primary thought is: Thank the Lord I was spared the torment.

I mean, can you imagine having to sit down one morning in June and spend four hours developing an exhaustive, coherent argument around the subject: Is truth preferable to peace?

Or: Does power exist without violence?

Or possibly: Can one be right in spite of the facts?

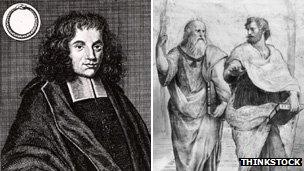

Perhaps you would prefer option B, which is to write a commentary on a text. In which case, here is a bit of Spinoza's 1670 Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. Or how about some Seneca on altruism?

I take these examples from my daughter's revision books. My heart bleeds for her, as I look at the list of themes that have to be mastered.

Ruby has chosen to take what they call a Bac Litteraire - the Literature Baccalaureat.

There are alternative, more science-biased versions of the Baccalaureat. They all include an element of philosophy.

But in the Bac Litteraire, philosophy is king.

It means eight hours a week of classes, and in the exams it has the top coefficient of seven. In other words, in the calculation of your overall mark at the Bac, it is philosophy which counts the most.

It also means having to master a host of what they call notions - notions, or themes.

Here are some of them from Ruby's books - consciousness, the other, art, existence and time, matter and spirit, society, law, duty, happiness.

And among the writers you need to refer to are Plato, William of Ockham, Kant, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Heidegger, Sartre.

Why this emphasis on philosophy in France?

Other countries have school-leaving exams which cover the history of ideas and religion and so on. But the French are very clear that that is not what theirs is.

The purpose of the philosophy Bac is not to understand the history of human thought but to leap into the stream that is the actuality of human thought.

If you learn about what Kant or Spinoza once said, it is not so much to understand their argument as to use their argument.

Napoleon launched the Baccalaureat in 1809, and philosophy was one of the subjects in the first ever exam (though back then it was oral, and in Latin, and only 31 males took it).

"I am awe-inspired by the change that has come over my daughter"

The idea behind philosophy was itself entirely philosophical.

In the newly created republic (and yes, I know Napoleon had just made himself emperor, but the point still holds) it was important to create model citizens.

Had not the great writer and thinker Montesquieu himself said the republic relied on virtue, and virtue consisted in the capacity of individuals to exercise their own freely-formed judgment?

So the purpose of teaching philosophy was - and remains, in theory - to complete the education of young men and women and permit them to think.

To see the universal arguments about the individual and society, God and reason, good and bad and so on, and thus escape from the binding imperatives of the now - by which I mean the dictatorship of whatever ideas are most pressingly forced on us in the day-to-day by government, media, fashion, political correctness and so on.

How wonderful, you cannot help thinking. What a great idea. Now that is what I call civilisation.

Or is it? I mean, maybe this is one of those very French situations where the theory is all very well, but somehow reality does not behave as it is supposed to?

Because one of the effects of having such an ideas-based vision of society, and elevating ideas to such heights, is that people actually start believing in them, and then maybe they start thinking the ideas are worth fighting for, or perhaps dying for, or perhaps even killing for. And then what?

Baruch Spinoza (left) and Plato (right, with Aristotle) are among the philosophers the students study

A few days ago, for example, a man shot himself dead in Notre Dame cathedral.

Dominique Venner was a philosopher and essayist of the far-right.

In his last blog post he quoted Heidegger saying the last second of a man's life had as much significance as all that went before.

Here was a man, arguably, who fell so in love with his own ideas that he decided to take his life. How very French.

But that is to be morbid. Back here at home, I am merely awe-inspired by the change that has come over my daughter since she started her philosophy studies.

A year ago she was utterly lost - panicked by the density and abstraction of it all. Today she is not just at ease, she is enthusiastic.

A world of thought has indeed been opened to her.

So is it absurd to desire the impossible? Can one ever be certain of being right? Is art real?

I'll have to ask her.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external