The adults who suffer extreme homesickness

- Published

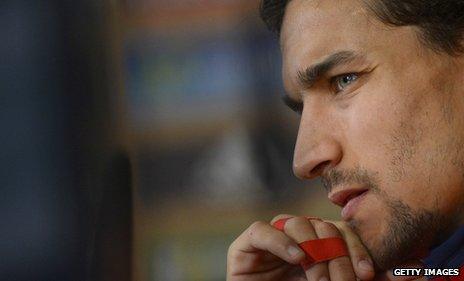

Footballer Jesus Navas, who is moving from Seville to Manchester City, has had a career shaped by homesickness so severe it stopped him playing for Spain. It's a condition that affects a surprising number of adults.

For years Jesus Navas was a staple of football gossip columns. Newspaper websites would link the jinking winger to a big money move to the Premiership. But a knowing reader would always point out that Navas was going nowhere. His homesickness would surely stop him.

For years Navas suffered so severely from homesickness that he could spend no great time away from Seville, itself less than 19 miles from his birthplace of Los Palacios y Villafranca. Anxiety attacks forced him out of training camps and pre-season tours.

Now it is said he has overcome his homesickness through counselling. But in an age of globalised working, there are many adults still struggling.

Navas rejected a move to Chelsea in 2006 because he feared he'd be homesick

Homesickness in adults is often associated with students moving out of home for the first time - research suggests, external that up to 70% experience it at some point - but as people increasingly migrate to bigger cities or even further afield, it's a feeling shared by many older people.

Relocating to another country can be a daunting prospect, particularly if you don't speak the language. Homesickness can have similar symptoms to depression, says psychologist Dr Caroline Schuster.

In extreme cases it can develop into a panic attack, she says, while it can also result in social withdrawal, sleep disruption, nightmares, and concentration problems.

British model Keisha Lall, 25, moved to New York in October last year. Despite normally loving to travel and explore, she's found it difficult to adapt.

"Because I feel lonely I like to sleep, stay home and stream programmes," she says, "[I'm] not very active compared to how I would be at home."

On the really bad days earlier this year, she says she'd often go home and cry.

Almost anything can trigger homesickness, says Schuster - a smell, a taste, even a colour.

For Argentina-based charity worker Fiona Watson, it's mostly visual triggers. "You see an image and it immediately goes straight to your heart.

"It can be from anywhere I have lived in Europe - and in my case it's definitely Europe, not one specific country - old farmhouses in Switzerland, village photos of the south of France… fruit and veggie markets in Paris."

While Watson can feel homesick for an entire continent, it usually resonates at a more particular level.

"People can feel homesick by moving just a street away," says social psychologist Dr Gary Wood. It's all about how we cope with change, he says.

Moving to new places involves having fewer "anchor points" in your life, adds Wood, and "some people tolerate this ambiguity [in their lives] better than others."

Literary references to homesickness go as far back as Homer's Odyssey. But the modern term was coined in the 17th Century to describe the feelings of Swiss mercenaries, who longed for their homeland while fighting elsewhere in Europe.

Much in demand for their skills with the pike and near-suicidal bravery, it was said that they were banned from singing Swiss songs on the basis that nostalgia would overwhelm them, leaving them useless.

In the 17th Century it used to be seen as a dangerous disease that people could die from, says Dr Susan Matt, author of Homesickness: An American History.

Gradually it came to be considered childish and immature, she says, ill-fitting to a culture of capitalism and imperialism.

But Schuster thinks there's been a counter-trend in recent years, which has made people less afraid of talking about it.

Olympic gold medal-winning rower Kate Copeland, from Teesside, admitted that she almost quit the sport, external due to homesickness while training in the south.

British actor Robert Lindsay recently discussed, external breaking down in tears on the side of a Hollywood freeway when Elgar came on the car stereo.

Soldiers typically spend many months away at one time, and often in hostile places.

"Some people get [homesickness] really, really badly," concedes Maj Charles Heyman, who has served on several continents and is now editor of Armed Forces of the UK.

"But the vast majority just get on with it," he says, and the Army's camaraderie tends to pull most through times of hardship.

In fact Heyman's most acute experiences of homesickness came during his civilian career after the Army, in which he regularly travelled for consultancy work.

The isolation he felt when staying alone in foreign hotels, along with being unable to share his experiences with anyone, was far worse than any homesickness endured while in the Army.

"No amount of luxury in a hotel could make up for the fact that you were on your own. It would gnaw away at you."

Modern technology can limit this isolation, allowing almost constant contact with loved ones wherever they may be.

"Skype is a lifeline," says Wood. It can allow grandparents a world away to still watch their grandchildren grow up, he says.

But it can also exacerbate homesickness.

"Skype and Facebook are great tools to keep in touch with everyone you miss from home," says Watson. "But at the same time actually seeing the people you love, the comfort of the homes you miss, photos of happy times all together over there… it kind of rubs it in [and] can actually make you feel worse off."

"Seeing my couch, my home, my friends together, sometimes makes me feel I'm missing out," agrees Lall, "It's everything I know and it feels far away."

Some might wonder why people suffering from homesickness don't just return home.

But it's not always that easy. Mixed-nationality marriages are ever more common, meaning that at least one partner faces the prospect of living away from their hometown forever.

It's this sense of permanence that Mike Burton, originally from London, found particularly difficult after moving to his wife's home country of Ireland in 1976 - even though he'd already lived abroad for a number of years.

"It took the best part of 15 years to come to terms with the fact that I was never going to move back to England," he says.

Even after so many years, he says he still feels 100% comfortable in England, compared to about 98% so in Ireland.

People need to build "support networks", says Schuster. In more extreme cases people undergo cognitive behavioural therapy.

Wood advises people suffering from homesickness to write down three new things that you've been grateful for every night, as well as three things you're looking forward to every morning.

With the growth of expat communities and internet shopping, materialistic home comforts can be easier to come by.

Homesickness can also bring your family together, Watson says.

"You learn to prioritise and fill your suitcases [on trips back to Europe] with what means the most to you when you are away from home - you cannot take family and friends, so you take food."