Glimmers of hope in Detroit

- Published

- comments

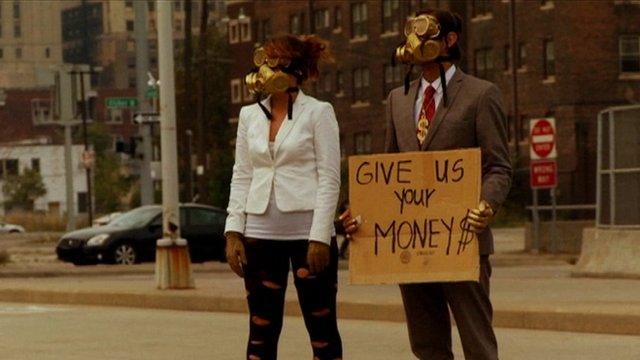

Despite decades of decline and mismanagement, there are signs of life in Detroit as private sector companies try to rebuild the city. But is it too late?

Outside the baseball stadium in Detroit the other week a man sold T-shirts printed with white capital letters on a black background: Detroit vs Everybody.

Being a journalist in need of a metaphor, it stuck in my mind.

Later, I met with Matt Cullen, the chief executive of Rock Ventures, which has invested in a number of Detroit-based businesses.

He's a native Detroiter who has spent almost three decades working for General Motors. He's now part of the huge revitalisation effort that's going on in the city's centre.

I told him about the T-shirt slogan and I asked, is that part of the deal, too, the Detroit spirit?

detroit challenge

He laughed, but also winced, because there are at least two ways to read the slogan. One is a plucky, never-say-die, it-will-rise-from-the-ashes kind of attitude. And the other is a late night, very drunk, who-wants-a-fight-before-falling-asleep-in-the-gutter kind of pose.

The latter is probably not how you want to sell America's most troubled city.

There's no escaping the fascination of Detroit. The first time I went, in early 2011, I was quite literally open-mouthed at the devastation. Outside the city's abandoned central railway station, on a bitterly cold winter's day, I gawped at the incomprehensibly large building.

The station is part of Detroit's decaying majesty, what is accurately and painfully called "ruin porn".

At one point a limo pulled up and disgorged a couple, he in tuxedo, she in a wedding gown, who spent 20 minutes or so being artfully photographed in front of the monument to the fall of a city. I really thought I'd seen it all.

But I had not. This last visit I headed out from my downtown hotel, down the vast, empty Michigan Avenue to get some food.

In the Corktown neighbourhood there's a funky burger bar, an artisanal coffee shop, a bustling barbecue joint.

There are startlingly few black customers - often none at all - which feels more than a little odd in a city that is overwhelmingly African-American.

But it seems churlish to grumble. That there is somewhere nice to eat and drink and meet a few minutes from the city centre, somewhere the young professionals who are now electing to live in the area might want to spend their start-up dollars, is a triumph in a city short of such things.

As I left, I looked up, and there looming over me in the warm night was the huge, beautiful, abandoned central railway station.

I had a wildly over-romantic surge of hope for the city that so much of the US so enjoys giving a good kicking.

There are unmistakeable signs of revival in the private sector, just as the city faces the final showdown with the creditors to whom it owes $15bn (£10bn).

A good deal of this is due to one man, Dan Gilbert, the founder of the Quicken Loans mortgage empire. He has gone against the trend of half a century by moving his white-collar staff into the city.

He and his colleagues have set up venture capital companies and tech start-up incubators.

He and his staff - their eyes ablaze with Motor-City-evangelism - organise design competitions for vacant lots, and spread the word far and wide that, in the immortal lyric of rock musician Ted Nugent, "Detroit City, she's the place to be".

The city centre is buzzing - there is a sense of purpose in the air, of momentum, of money, of enterprise.

Ross Sanders runs Bizdom, a tech start-up incubator that has recently outgrown the building that housed it and has had to move to another office.

At Bizdom I chatted to a couple of start-up 20-somethings, Erik Torenberg of Rapt.fm, and Michael Sharber of Greenlancer.

Mr Torenberg, a skinny rap enthusiast from New Jersey, said that the first thing his relatives asked when he told them that he was moving to Detroit was: "Is it safe?"

He bursts with enthusiasm for the city.

Mr Torenberg studied at the nearby University of Michigan, but not once ventured into Detroit. Now he can't get enough of the place. And Mr Sharber, who grew up in Detroit, invites me to watch his volleyball game, played in the shadow of a vast abandoned factory.

But if Detroit is to rise again it will need more than the enthusiasm of the private sector. It will need a properly functioning public sector.

There is no sign of that coming along anytime soon.

"We go into buildings," the fire chief told me, "and grapple with the devil."

He was standing outside his station on a warm summer's evening as a smell of herbs wafted out from the kitchen. Dinner time was coming for his 12-man company.

The station was in better nick than the immediate neighbourhood. Across the way, waist-high grass grew untended. A long-closed supermarket was covered with graffiti, its green awning torn and hanging at a crazy angle.

Upstairs, huge noisy fans battled with the summer heat in the company's dormitories. The fire chief had an office out of the 1970s - clipboards and to-do lists covering one wall, a beaten-up desk, an old TV opposite with a washed-out screen.

I thought of the shiny new offices of downtown, all glass and steel, climate controlled with flat-screen TVs and famous-name coffee machines.

Apart from the odd computer, nothing in the station that had been purchased in the last 20 or so years. And, with all due respect to the company, there was no-one new in it either. Apart from one recent transfer all the men were middle-aged or more.

How long can it go on like this?

In his first report a few weeks ago, the city's new emergency manager wrote of Detroit's public sector being, external "dysfunctional and wasteful after years of budgetary restriction, mismanagement, crippling operational practices and, in some cases, indifference or corruption".

For 50 years Detroit meant mass assembly, it meant the automobile, opportunity for an uneducated - often black - workforce.

Then it came to represent the decline of the Great City, the collapse of urban government, even the end of the American dream.

There is huge energy in the city. But saving Detroit is not a done deal.

"We hope for better things; it shall rise from the ashes," goes the city motto.

Or, more pithily, Detroit v Everybody.

- Published23 February 2012

- Published23 December 2011

- Published13 September 2012