How true are films about state snooping?

- Published

Stories of surveillance have been cinema fodder for decades. Given what we know about how real-life spies work, how closely do these sometimes fanciful tales resemble reality?

The story of Edward Snowden - the intelligence contractor who leaked information about secret government surveillance programmes - has the makings of a great film. Hollywood has long found compelling tales in stories of wiretapping, spying and rogue agents.

Although dystopic movies have been made ever since Hollywood existed - think Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times in 1936 and Metropolis in 1927 - the genre has been prevalent since the 1970s.

"It's very much post-Vietnam, post-Pentagon papers, that suspicion of the national security state," says Michael Berube, director of the Institute of Arts and Humanities at Penn State University.

Watchful superiors in 1927's Metropolis, set in 2000

But what kind of story Snowden's will be has yet to be determined.

Perhaps it begins with our hero in front of a computer. Conventionally handsome, save for the heavy-rimmed glasses that are shorthand for "geek", his fingers fly over the keyboard until he finds something he shouldn't. Everything changes. Our hero befriends an outside-the-establishment reporter. He races through Hong Kong, trying to avoid the people out to get him for exposing the truth, one man against the machine.

Or it begins with a villain. Cast in a sickly glow from the light of his computer screen, his lightening-fast fingers expose secret after secret, and soon information designed to keep America safe - information the villain swore to protect - is exposed to the entire world, including terror networks. Then it's up to a plucky team of US agents to track him through Asia before he can do more damage.

Both these film treatments have popular Hollywood precedents. Both reflect conflicted attitudes about the role of surveillance in modern society.

"On the one hand, you have government seen as the power that is surveilling people inappropriately," says Vincent Casaregola, incoming director of film studies at Saint Louis University.

"Other times it's the stalker or the criminal, and it's the power of government and police to surveil that gives them the power to catch the criminal. It's a mixed bag."

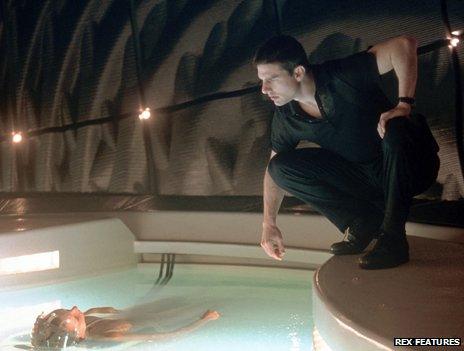

Films such as Minority Report and Gattaca, where the protagonist is trapped and freedoms are limited by an all-powerful and all-knowing government, tap into a primitive fear, says Casaregola.

"Everyone knows they are potentially a victim of predation. When you are out in the open and can be seen, you know there is something in the bushes that might be watching you.

"Though we want to deny it, we do want to be on the viewing end. We want to know what other people don't know."

After all, along with fears of being stalked comes the desire to be the one in the bushes, doing the stalking. That is seen in films such as:

Zero Dark Thirty - hi-tech surveillance is used to track down Osama Bin Laden

Hackers - young computer hackers try to break into company and government databases in the name of freedom

Sneakers - a team of hackers tracks down a code-breaking machine, rescues it from corporate and government interests, and uses it to bankrupt certain organisations in favour of pet causes.

While the use of torture and the depiction of terrorism has shifted tremendously in films since 9/11, says Berube, the depiction of state-sponsored surveillance has remained consistent for decades, on display in films like THX 1138 (1971) and Enemy of the State (1998).

"This has been a pervasive fear and anxiety, long before the Patriot Act, long before this latest news," says Berube.

"In some ways it's almost like the realisation of fears you already had."

And while the technology has changed, some of the messages remain the same.

"There's always this longing for a simpler time," says Carolyn Guertin of the Transart Institute in Berlin.

"They're fairy tales or fables that try to escape contemporary reality."

Brazil charted a lowly bureaucrat's transformation into enemy of the state

Moviegoers may line up to buy tickets for these fables, but they're less idealistic in real life. Witness a recent survey which finds that 56% of Americans, external find the NSA's actions acceptable.

Indeed, some films - such as David Wittenberg's Code 46 - decry the authoritarian controls of a surveillance state while also recognising that in some cases, the state knows best.

In that film, two lovers are punished for violating government rules about who can travel and who can engage in physical relationships. But these rules prove to be protective. A man given false papers so he can travel to do research dies from a disease, his susceptibility to which prevented his official clearance in the first place.

"You try to buck the system and the person you're doing the favour for ends up dead," says Berube.

That has some film theorists arguing that movies need to do a better job not just telling stories about surveillance, but examining what it means to be watched - and what we lose when we are.

"These films are about surveillance falling into the wrong hands or the right hands, but there's never an examination of what it does to people and what the costs are," says Lance Duerfahrd, a professor of English at Purdue University.

"What is privacy and what is private? Why is privacy a crucial space that needs to be defended? There's no indication of one's inner or private world. It's taken for granted and being compromised, and the film goes on from there."

Still, he predicts that the Edward Snowden story - possibly starring Bradley Cooper? - will someday make its way to a theatre near you.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external