How accurately does Blackadder reflect history?

- Published

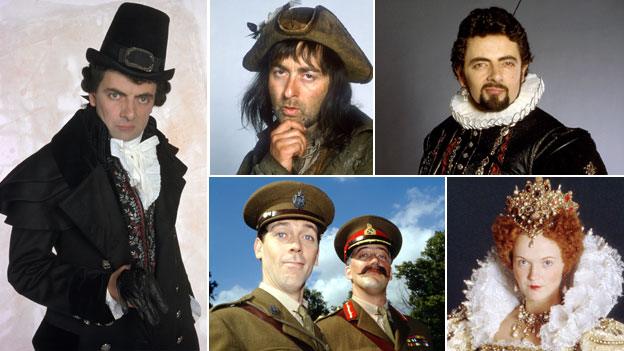

As fans of Blackadder celebrate the 30th anniversary of the comedy's first broadcast, its stars Tony Robinson and Rowan Atkinson are recognised in the Queen's Birthday Honours. Its fast-and-loose attitude to real events and characters is part of the appeal, but how close is any of it to real history?

Think of the Prince Regent, later George IV, and what images flood your mind?

For anyone who has seen Blackadder it's hard not to think of a bewigged Hugh Laurie shouting "tally ho".

A World War I general? Does Stephen Fry's General Melchett lamenting the death of Speckled Jim come to mind?

The four series of Blackadder are replete with history.

"History was my big subject at school," says producer John Lloyd.

"[Writer] Richard [Curtis] and I had curiously read the same book called Looking at History by RJ Unstead. It said things like: 'In the middle ages women wore wimples'."

Ben Elton [writer from the second series on], being the nephew of eminent Tudor expert GR Elton, also brought a hefty dose of historical enthusiasm.

The pilot episode, never broadcast, was very different to the Blackadder people know today.

"It had a feeling of Game of Thrones, set in an indeterminate period of history, not rooted in real events," says Lloyd.

"I said we have got to tell people where this is set."

Thus The Black Adder was set in 1485. In this world, Richard III is succeeded by (the fictional) Richard IV, who is later written out of history by (the real) Henry VII.

But the later series come closer and closer to reality. Blackadder II revolves around a childish and intensely capricious Elizabeth I (Miranda Richardson). Blackadder The Third tackles the Regency period with a hapless Prince George.

Blackadder Goes Forth is set mainly in a WWI trench. "In Blackadder Goes Forth they had no option," says Jem Roberts, author of The True History of the Blackadder.

"They had run out of licence to be completely anarchic. There was so little they could get away with in 1989. Lots of people who had fought in the trenches were still alive."

The end result of the four series can be viewed as a kind of satire of school history books and the weird mishmash of fact and exaggeration that is left in many people's heads a couple of decades after their last history lesson.

The costumes were always accurately researched, says Lloyd, and while the dialogue had to be anachronistic to be funny, there were occasional bouts of fact-checking.

A line from the first series was to be: "I curse you, and hope that something slightly unpleasant happens to you, like a potato falling on your head."

As Walter Raleigh was yet to deliver the potato to England this was changed in the final draft to "onion", says Lloyd.

And it's pleasing that more than two decades after the last series finished, it's still used to enthuse children about history, he says.

Here are three bits of history from the series put under the microscope:

The Prince Regent

The Prince Regent - as portrayed by his contemporaries, and by Hugh Laurie

Blackadder portrayal: Drunken, philandering idiot of spectacularly limited grace and intelligence.

Reality: Unfaithful and a drinker, but a noted patron of the arts with no reputation for stupidity.

The Prince Regent of Blackadder the Third has only three life priorities - sleeping in, carousing and seeking out the company of as many ladies as possible.

His limited intellect is spelt out by Blackadder in the following exchange:

Prince George: Someone said I had the wit and intellect of a donkey.

Blackadder: Oh, an absurd suggestion sir, unless it was a particularly stupid donkey.

The Regent that Blackadder has to deal with can be relied on to do the foolish thing - whether it be ennobling Baldrick or confusing a play with real life.

The real prince - who acted as regent for his mentally ill father, George III, and was later crowned George IV - certainly was a philanderer, both before and after his unhappy marriage to Caroline of Brunswick.

"He had a miserable childhood without love," says Tom Ambrose, author of Prinny and His Pals.

"His philandering was usually with very portly ladies - mother figures. He was looking for love and security."

George's appetite for drink and tendency to spend money was also well known at the time.

The day after his funeral, in July 1830, the Times was happy to label him an "inveterate voluptuary".

It said: "Nothing more remains to be said or done about George IV but to pay - as pay we must - for his profusion; and to turn his bad example to some account, by tying up the hands of those who come after him, in what concerns the public money."

But whatever his spendthrift bent, he was no idiot, says Lord Baker, a fan of Blackadder and author of George IV: A Life in Caricature.

"When it comes to the Prince Regent he was presented as a dandified oaf - usually drunk and stupid. That's pretty unfair to poor old George IV."

Instead, we might recognise his patronage of architect John Nash, his role in the reshaping of London and his major contribution to the royal collection of art.

"He was the greatest town planner - everything from Regents Park to the Nash terraces, Oxford Circus, Piccadilly Circus, the Mall. He totally remodelled Windsor Castle," says Lord Baker.

"He was a tremendous patron of the arts. He was also fat and a dandy and drank a lot."

And at least one episode in Blackadder the Third is absolutely true to reality, says Jem Roberts.

"When the Prince Regent became George IV he was known to dress up as a butler when guests came to his house, echoing Blackadder."

Field Marshal Douglas Haig and WWI generals

Blackadder portrayal: Haig is callous, and fictional General Melchett is an unthinking upper class buffoon.

Reality: Years of vigorous academic debate, but revisionist view of Haig now taken by many.

In Blackadder Goes Forth, the eponymous infantry captain sums up his field marshal's strategic masterplan with the line:

"Haig is about to make yet another gargantuan effort to move his drinks cabinet six inches closer to Berlin."

General Haig visits the troops, 1916

In the final episode, on the phone to Blackadder, Haig is seen casually knocking over model soldiers on a mock-up battlefield and sweeping them up with a brush and pan.

The visual allusion to his callousness is obvious.

It's in the tradition of Alan Clark's book The Donkeys, which follows on from critics like strategist and military historian Basil Liddell Hart and former Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

In his diary, Hart wrote that Haig was "a man of supreme egoism and utter lack of scruple - who, to his overweening ambition, sacrificed hundreds of thousands of men".

Haig's tactics were characterised by critics as reliant on massive bombardment and frontal assaults with little care for the casualties that resulted, such as on the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

But there has been a wave of revisionist history about Haig in recent years.

"The real Field Marshal Haig was certainly not a callous man," says Gary Sheffield, author of The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army.

"He was commanding the largest British army ever. Whatever he did you ended up with lots and lots of casualties.

"In the end he was a successful general. His record was no worse than most other commanders and rather better than many of them."

The other general in Blackadder Goes Forth is even more cartoonish. Known for his catchphrase "Baaaaaah!", Gen Melchett with his exaggerated public school ethos and pitiful intelligence represents another side of the post-WWI criticism.

"As far as the portrayal of Haig, Geoffrey Palmer plays Haig, but in effect Melchett is an amalgam of Haig and John French and the other generals so Haig appears twice," says Sheffield.

But Haig and his fellow WWI generals were operating in a period unique in military history, he argues. Armies had grown so big that generals could no longer cover their whole extent in person, while the radio technology that made manipulating large armies in WWII possible was yet to be invented.

Haig and the other generals learned lessons which led to the sweeping victories of 1918.

Sheffield is still a fan of Blackadder and, having given lectures alongside John Lloyd, enjoys using it as a starting point when tackling preconceptions about Haig and the other generals.

"It is a very good and clever satire not just of WWI but also the popular perception of WWI.

"The problem is that it misses out 1918. The very final scene is set in 1917. It doesn't deal with the victory."

Of course, the debate over Haig is still very much live and there will be plenty who dispute the revisionist view vehemently.

But he certainly wasn't a Melchett-esque dolt.

"Whatever else he might have been he clearly wasn't stupid," says Sheffield. "Haig must not be judged solely on his role as a battlefield commander. He reorganised the Army and trained the Army. To get a true picture we need to see him in the round."

Richard III

Blackadder portrayal: Jovial and pleasant, as played by Peter Cook.

Reality: Recent excavation led to renewed interest in Richard's reputation and how it was besmirched by the Tudors. Still not cleared of murder of Princes in the Tower.

"At the very, very start of the entire Blackadder saga, Peter Cook plays Richard III as a jolly king, loving his nephews," says Roberts, who believes the often less well-regarded first series is still a classic.

When people think of Richard III, the portrayal from Shakespeare of a hunchbacked Machiavellian persists. Everyone knows that the Princes in the Tower were killed by Richard III.

But, as anyone from the Richard III Society might ask, what is the concrete evidence against him?

The historical revising of his reign has been going on for much of the 20th Century and reached its zenith in the recent tussle for the right to bury his body. Many more people are now familiar with the Tudor attempt to blacken Richard's name.

"Who knew in 2013, Henry VII would be seen as a liar and a propagandist?" says Roberts.

And there is something fundamentally comic about the fact that Richard's body had to be excavated from a car park in Leicester.

"It echoes Blackadder rather brilliantly," notes Lloyd.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published14 June 2013