How do you prepare for a lifetime of renting?

- Published

In much of the UK many young people have no prospect of getting on the property ladder. So how can they prepare for decades of renting?

There's a long-held view in the UK that people rent only because they have to.

They rent when young, when it seems a rite of passage. They rent before they've decided where to live permanently. But most of all, they rent because they can't yet afford to buy.

Many renters enjoy the freedom.

They live in an area where they could never afford to buy. There's less hassle and responsibility. If the boiler breaks, the landlord will get it fixed.

But at a certain age, perhaps in one's late 20s, there's also a nagging fear. The clock is ticking. People use phrases like "rent's just dead money".

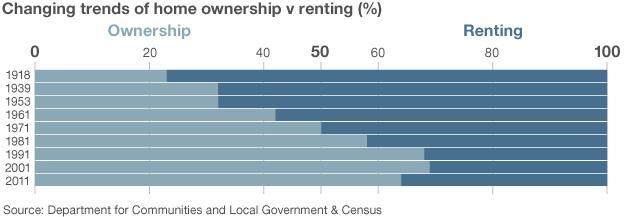

Right To Buy in the 1980s led to a boom in home ownership. In 1988 only 9% were privately renting homes. But in recent years, as house prices have risen and the economy has stalled, the move has been in the opposite direction.

In 2010 the Chartered Institute of Housing forecast that by 2020 a fifth of homes would be privately rented.

Evening Standard columnist Richard Godwin has just bought a house. It's been 10 years of saving up his salary, getting help from his parents and his wife's parents.

Renting carries a stigma. "There is a social expectation to own a house at a certain point. You're made to feel like a second-class citizen if you rent."

New figures predict that a 25-year-old single person in London who wants to buy will be 54 by the time they can afford it.

But for the majority of people in their 20s across the whole of the UK, buying a house is becoming a decade-long pursuit. They face a pincer movement of high and rising house prices, but stagnating wages.

Research by homelessness charity Shelter estimates that the average single person will have to save for 14 years before they can afford a home.

In March this year, Shelter research suggested the cost of renting had risen by £300 a year over the past year. Department for Communities and Local Government figures estimate that the average renter pays £160 a week in England. Meanwhile, the average owner-occupier pays £143 a week on their mortgage.

Young people's reaction seems to be one of resignation. It will take time to buy.

The word "precarious" crops up a lot in conversations with renters in the UK.

Tenancy agreements of just a year are the norm in many places, with either party able to terminate at the six-month mark where a break clause is included.

"If you want to have a child, you know it's almost impossible in private rented accommodation as you could be thrown out," says Shiv Malik, a journalist and co-founder of the Intergenerational Foundation.

But with more people forced to rent longer, how can people prepare?

The fall and recent rise of renting in England and Wales

One way is to look at the rest of Europe. Long-term renting is normal in many places.

Figures for 2011 show that 13.3% of people in the UK privately rent (with social housing, the renting figure is 32.1%). This compares with 51% in Switzerland, 40% in Germany and 32.8% in Denmark. European countries provide much greater legal protections.

Renting itself needn't be a disaster, Malik says. "In Germany people who rent have a right to make it their home."

But in the UK it can feel like a second-class system. There are limited protections.

Landlords can typically boot people out of rented flats with two months' notice once a fixed term has elapsed. Sometimes tenants refuse to go and force the landlord to seek an accelerated possession order. (They have 14 days to appeal against this before a judge would typically award a possession order and give the tenant 14 or 28 days to leave.)

In countries such as Germany, Switzerland or Belgium, long-term contracts and more flexibility give tenants the chance to plan for the future.

But with the pool of renters in the UK rising, so is their clout. There are more of them. And they are becoming more vociferous.

Recent legislation is more renter-friendly than before. The tenancy deposit protection scheme, external has given peace of mind to renters worried about losing their deposit on a technicality.

There is nothing to say that other measures could not be achieved by pressure on this or a future government. Many renters would welcome longer contracts where increases are pegged to the rate of wage inflation.

Banning lettings agents from charging fees to tenants would be another move that would please many renters.

Neither of those measures are currently in the pipeline, so how can renters make the best of the current situation?

Finding a friendly, trustworthy landlord can really help, says Godwin. "I've been quite lucky as I was renting somewhere for seven years. My friends are amazed we've managed to stay somewhere so long." Building a strong personal relationship with a landlord can help.

Penny Anderson, who writes the Renter Girl blog, says the big picture is uncertainty, but there are coping strategies. If possible avoid letting agents and go direct to the landlord, she says. Then find someone you click with.

For the people who rent through an agent, using word of mouth to find the most honest and reasonable is always sensible.

And there's nothing to say you can't personalise your rented home. In a non-permanent way.

"Find a way to make your temporary home a proper home," says Anderson. "Try and have space where you can [entertain] friends when they come around. And make space for plants and ornaments." But don't accumulate too much stuff - clutter is depressing.

If the letting agent is only interested in a short-term let, see if you can go direct to the landlord. Tenants have a legal right to contact the landlord during their tenancy, she says. "Go to the landlord and see if you can get a longer tenancy agreement."

And of course, one of the key ways for long-term renters to cope mentally is to keep their eyes fixed on the dream of buying somewhere.

The UK builds many fewer houses than it needs every year and has done for a long time. But there's nothing to say that won't change under this or a future government.

Then there will be plenty of renters who dream of another property crash helping them out.

With prices currently rising against a background of a stagnant economy, and that rate of increase tipped to rise with the effect of the government's Help to Buy scheme, there are all the ingredients of another crash.

Many renters focus on saving money, hardening themselves to making sacrifices so they can build up their deposit.

Young people in the most expensive parts of the country - like south-east England - may need to ask themselves if they could do their job anywhere else.

Kate Garner, 24, who lives in Brixton, London, plans to move back to Manchester to settle down. She pays rent of £500 a month on a salary of £20,000 a year.

"My friends in Manchester are definitely talking about buying houses. Up there they can consider it, whereas I can't."

And however depressing it might seem for individuals, the increasing number of people renting will inevitably lessen the whiff of social stigma. Older renters are going to become more common.

Anthony Lewis, 40, of Brighton, has been saving up for a deposit for almost a year - about £500 a month - to buy a property on his own.

He says he is only just approaching the financial situation where saving is a possibility.

Lewis says he wouldn't mind renting if the situation was more like it is in Europe - the rents are lower and it's more stable.

"I've been renting for more than 20 years. It's just the norm these days. Renting is just what people have to do. It's the state of the nation when it comes to housing.

"I can't afford a pension so I want to own my own home. It provides such security - much greater than a pension. I want to do it, I just don't how it's going to happen."

Additional reporting by Tom Geoghegan in the US

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external