A Point Of View: Solstice and the lack of symbolism in Britain

- Published

The Church's appropriation of many pagan festivals has left an important gap - the summer solstice. Tom Shakespeare casts an envious eye at the seasonal rituals celebrated in other countries and urges more symbolism in British holidays and traditions.

If in this year of 2013, an interplanetary anthropologist came to England for fieldwork, what would they discover? On a variable Sunday each spring, we give our children more chocolate than is good for them, eat roast lamb and visit garden centres.

On the last day of October, we dress the kids up in old sheets, black bin liners and plastic fangs, and send them down the street to extort sweets from our neighbours. A few days later, we gather around a bonfire, set off rockets and celebrate the execution of a Catholic conspirator. The following month, we get together with our birth families to exchange gifts, to eat too much and to argue.

And that's about it.

The word "festival" is now reserved for occasions when people who are young, or would like to be, huddle together in a field to listen to music in the rain and shop for ethnic clothing and candles. And get inebriated.

Some 1,500 years ago, our Anglo-Saxon and Celtic ancestors had a much better idea. They celebrated regularly to mark the passage of the seasons that governed the natural world around them and the cycle of the sun, which gave them light and warmth.

Life being nasty, brutish and short, they made the most of these moments of hope and plenty. Like most religions, pagans had festivals such as Yule, and the spring fertility festival, Eostre, not to mention Beltane, Lammas, Samhain and so forth.

The arrival of Christianity meant that people had to give up sacrifices and the more sexually adventurous forms of celebration. But in return, the new religion offered an increasing roll call of saints - each of whom was owed their day of partying.

The pagan holidays were recycled as Easter and Christmas. Shrove Tuesday compensated for the rigours of Lenten fasting, and gave a great excuse for a festival from Basel to Brazil via New Orleans.

At the end of summer came the harvest festival, that strange Anglican anachronism now centred on the ritual donation of tinned goods and unwanted vegetable marrows. All Souls' Day, on 2 November, was the day people remembered and celebrated their dead, although Christianity has never given ancestors enough credit.

But the Church's appropriation of pagan festivals left one rather important gap, at least in Britain. I am talking about midsummer, the summer solstice, which this year fell on 21 June at 5am. Unless you are living in Cornwall or Edinburgh or Binchester, or are one of the 56,620 Britons who identified themselves as pagan in the 2011 census (up from 42,262 in 2001), you are highly unlikely to take any notice whatsoever of midsummer.

And that makes me rather sad.

It also makes Britain somewhat unusual. For example, the Nordic countries mark midsummer rather well. Perhaps because they know what it is to experience long months of darkness, they relish their summers, and gather each June for communal celebrations.

Sweden does midsummer in the most elaborate fashion, with the midsommarstang maypole and dancing, and flowers in the hair. Norway's midsummer rituals entail bonfires, preferably out in nature, near a fjord or river. Finns and Danes also go for the fire, underlining that midsummer is a festival of light.

Solstice around the world

Norway: People attending a concert marking the midnight sun in Tromso, where there are 24 hours of sun during the peak of the summer

.jpg)

China: People dressed in traditional Han costumes offer fruits as scarifices to heaven, during a ceremony to mark the winter solstice festival, started during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD)

India: Hindu devotees worship the sun god on Makar Sankranti, a Hindu holy day marking the winter solstice when the sun transits from the astrological zone of Sagittarius to Capricorn

Belarus: Girls jump over a fire during celebrations for Ivan Kupala, the feast of St John the Baptist, a traditional Slavic orthodox holiday celebrating the summer solstice

Bolivia: Aymara natives arrive in Khona bay for summer solstice celebrations on Isla del Sol, Lake Titicaca, in December

Bolivia: The winter solstice is even more important to Aymara natives, as it marks the Aymara New Year, and was made into a Bolivian public holiday in 2010

Macedonia: These people are practicing yoga during summer solstice at the ancient astronomic observatory of Kokino - it is more than 4,000 years old and is filled with astronomical markers on its rocky surface

El Salvador: People take part in a Mayan ceremony to celebrate the summer solstice at Tazumal archaeological site, in Chalchuapa near San Salvador

US: In recent years Times Square in New York City has been brought to a standstill during the summer solstice by a mass yoga event

Austria: People watch a traditional midsummer festival bonfire to mark the summer solstice - bonfires are also used to mark the summer solstice in Norway, Finland and Denmark

I know what you're thinking. Norway, Sweden, Finland… these are the lands of the midnight sun. Here in Britain, it would be nice to have some midday sun, let alone midnight.

True. But it's not just in northern latitudes that midsummer is taken seriously. In many Catholic countries, such as Portugal and Brazil and Argentina, the festival of St John has recuperated midsummer, and turned it into a celebration that needs no midnight sun to be meaningful.

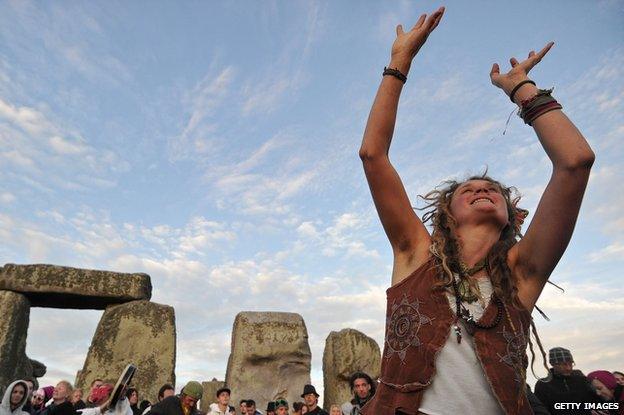

I would not for a moment suggest that we revert to the liturgical calendar, let alone to paganism. Druids parading at Stonehenge seem to me as contrived as Morris dancers. But I believe that we are poorly served when it comes to festivals and celebrations. Our working lives are broken up only by the school holidays, by the new year sales and by bank holidays.

And what a terrible thing bank holidays are. Just blank spots on the calendar that are entirely devoid of symbolism.

When Sir John Lubbock, a banker and politician, introduced the bank holiday in 1871, in the era where working people did very little other than work, they were welcomed with open arms by the exhausted populace. But now we are entitled to at least four weeks' regular holiday, we don't know what to do with the imaginatively named Early May Bank Holiday, Spring Bank Holiday or Summer Bank Holiday.

Alain de Botton, in Religion for Atheists, proposes that "those of us who hold no religious or supernatural beliefs still require regular, ritualised encounters with concepts such as friendship, community, gratitude and transcendence".

If by this he means we need some better festivals, I rather agree with him. When I look at other cultures, I feel a strong sense of festival envy.

De Botton mentions the Buddhist Tsukimi ritual, when people gather to view the harvest moon, and the Jewish festival of Birkat Ha Ilanot, which marks the first blossoming of spring. In Japan too, the seasons are celebrated - I was in Tokyo in April for Hanami, when the parks are full of people picnicking and admiring the cherry blossom.

Druids celebrate the Autumn equinox on Primrose Hill, London, in 2009

One reason that I like the idea of festivals is that they give rhythm to the year. Without regular and repeated moments, 365 days can just become a whirl, our busy lives offering no moments to pause and reflect.

In a country like Britain with real seasons, the annual cycle of the earth's movement around the sun has significance. It was only as I was considering this topic that I remembered that the word "equinox" refers to the two days a year when night and day are the same length. If we don't mark such moments, then I fear that our years will just become a featureless smudge in time.

When I moved to Gateshead in 1991, I had the great fortune to meet Andy Gibson, an inspirational community worker, together with a bunch of his mates, and I joined their men's group. Please don't think this was anything to do with drumming or native American rituals. This group was all about friendship. And beer. Each and every solstice and equinox, we would gather in the Central, a tiny pub in Gateshead town centre, and drink pints and catch up and take stock and occasionally sing.

The second important point about festivals is that they bring people together. In the modern age, communal moments are few and far between, but when they happen, they are very memorable. Whether prompted by disasters such as the assassination of President Kennedy or the death of Princess Diana, or by great celebrations such as VE day, the millennium or the London Olympics, these are days when everyone is talking about the same thing and the normal routine is set aside.

And that seems to me important in life. We need moments to connect with each other and come out of ourselves.

I'm not suggesting we should be worshipping anything, neither God nor Mammon. But wouldn't it be good, if we could get together at regular intervals, with family or with friends, to take stock and commune?

At midwinter, we could celebrate the shortest day, and look forward in hope to the coming of the light. At the spring equinox, it's the time to be thinking of fresh starts. The end of summer brings harvest, a moment of thanks for what the earth has given us. On 2 November, I'd like to light a candle to remember my father, and departed friends like Andy Gibson. And midsummer should be a celebration of light and growth.

The sociologist Robert McIver writes that "the healthy being craves an occasional wildness, a jolt from normality, a sharpening of the edge of appetite, his own little festival of Saturnalia, a brief excursion from his way of life".

Do me a favour. Do something different for midsummer next year.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external