Dagestan and the Tsarnaev brothers: The radicalisation risk

- Published

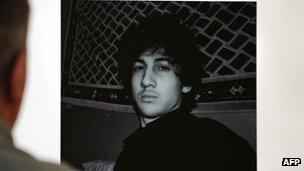

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the younger Boston marathon bombing suspect, will appear in court in just over two weeks. In Dagestan, the Russian republic where the brothers lived before emigrating to the US, few believe he is guilty. But an Islamist insurgency has been under way for years here - and it's all too easy for young men to become radicalised.

In a bare apartment in an unfinished block in Makhachkala, Zubeidat Tsarnaeva is poring over pictures on a laptop. The four still images revolve on a loop. Tsarnaeva rocks gently, waving her hand at the faces on the screen.

"Look at him," she implores. "Look how he loves life, he loves children. This is my Dzhokhar."

She is speaking of her younger son, who is in custody in the US, awaiting his first court appearance on 10 July for his alleged role in the Boston bombings. His older brother, Tamerlan, died in a police shoot-out during the ensuing manhunt.

Their mother is speaking to me just after returning to the Dagestani capital from Kizlyar, where she had been mourning the death of her brother (from natural causes). She is dressed from head to toe in layers of black. When she speaks - in English - of her sons, her large eyes blaze with passion.

"I raised them and gave them mother's love," she insists. "The word 'killing' in our house had no place. So of course I'm sure that my kids would never do this."

Zubeidat Tsarnaeva: "The word killing, in our house, had no place"

Ms Tsarnaeva says that she is planning to return to the US next month for Dzhokhar's court hearing. She has an American passport after she and her husband Anzor took their family to the US in 2002. It will be her first trip back since the bombing and she says she is nervous, but wants to support him.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was shot and injured in the manhunt that killed his brother, Tamerlan

"I will not let anyone to take my son away," she says. "They took my Tamerlan away but I will not allow them to take away my Dzhokhar." And she is defiant in her hope: "I really hope my son is not going to be long there. As soon as my son gets out, I will take him, I will grab him, and I will leave that country."

That country, the US, has been the focus of her anger, on the previous occasions when she has spoken out. Now she attempts to reach out to those who may be about to sit in judgment on her son: "If I expressed something like that, I want Americans to forgive me. I want them to know I have nothing against them."

But what of Tamerlan, her older son? One of the key questions in the Boston investigation is what happened during his six months last year in Dagestan. Was he radicalised? Did he fall under the sway of militants? His mother describes a wide arc with her arm, to indicate quite the opposite: "He became more non-radical, to love life," she argues.

Bombings are common occurrences in Dagestan

Details of Tamerlan's stay in the restive Russian republic remain sketchy. But I spoke to some of the leading Islamist figures who did spend time with Tamerlan last year.

They belong to an organisation called The Union of the Just. It describes itself as a human rights group, cataloguing and campaigning against the abuses of the Dagestani authorities, in the fight against Islamism.

There is a large overlap between membership of the Union of the Just - legal in Dagestan - and membership of Hizb ut-Tahrir, an organisation which campaigns for a global caliphate, and which is proscribed in Russia.

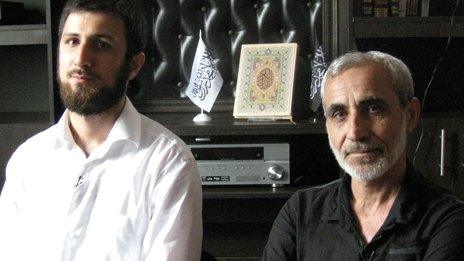

Magomedov (L) and Zukhumov met Tamerlan Tsarnaev several times

The Union's leader, Magomed Kartashov, is currently in jail. The deputy leader, Mohammed Magomedov, spoke to us in the Union's offices, just after midday prayers. "Most people in Russia don't believe the brothers are guilty," he says with quiet assurance. "Objectively, there are many unanswered questions."

Next to Mohammed sits the older man who had just led those midday prayers. Zukhum Zukhumov is a philosophy professor with a tightly-cropped white beard and a courtly, almost quaint, command of English small-talk.

He reverts to Russian to add his voice of scepticism to Mohammed's. The bombing "was all so obviously staged," he says. "It was organised with Moscow to show that Russia is not coping."

Professor Zukhumov says that, like Mohammed, he met Tamerlan Tsarnaev several times during Tamerlan's six months in Dagestan.

"He was tall, good-looking, and intelligent," says Professor Zukhumov. "He read Turgenev and Dostoyevsky. It's absurd to think he was inclined towards radical ideas."

In the same breath, though, Professor Zukhumov describes Tamerlan's "naivety, his openness, his simple nature".

"I guess these kinds of people are useful to some sinister forces: very likely certain conditions were created, he was pushed on to that path. It was not all the Tsarnaev brothers' own free will. It was a trap." he says.

Russian forces have been trying to crush the insurgency in Dagestan since 1999

It is certainly true that most people in Dagestan appear not to believe that the brothers are guilty. Slightly less widespread, but still the majority view, is that the region is "nowhere near as bad as you see on the TV".

Violence has in fact become so routine here that it barely makes it on to TV. The week before our trip, at least 19 people (16 Islamist guerrillas, three members of the Russian federal security forces) had been shot dead.

Our driver, who collected us from the airport, was the first to insist that talk of unrest was overblown, though he was, I noticed, discreetly carrying a gun. He delivered us to our hotel, where the man on the door was carrying a semi-automatic full-size Uzi pistol.

Dagestan translates as "land of the mountains"

In Dagestan there are many young men who are inclined towards radical Islamism, whether or not Tamerlan Tsarnaev fell in with them. One, 29-year-old Magomed Khadushkaev, left his wife and two-year-old son last year, to join the insurgency and go into hiding - termed here "going into the forest".

Khadushkaev is thick-set with sloping shoulders. He has a soft voice and doleful eyes. When we meet, it is only seven days since he walked out of the forest, and turned himself in to the authorities. We talk under a cherry tree, laden with its sour fruit, in Khasavyurt, the town closest to his village.

We are in western Dagestan, close to the border with Chechnya.

He speaks in short sentences and fatalistic tones. His story is that some of his village were involved in the radical militias, and that he began by just "helping them out", and then he got "carried away" and joined them.

Khadushkaev is currently being "rehabilitated" after spending time with the insurgents

Khadushkaev clearly does not want to say anything which might upset either the local security forces who are - unusually - allowing him to begin the process of "rehabilitation", or the remaining forest fighters who may wish to punish him for his defection.

He says that he was with a small band of other guerrillas - at first 20, and then just seven - who were planning attacks with Kalashnikovs and IEDs against Russian security forces in neighbouring Chechnya, before moving their target to Dagestan.

The enterprise sounded astonishingly inept. Food - tinned meat and porridge - would be bought by one of the fighters from a local market. Khadushkaev was in touch with his mother (who was imploring him to come home), and occasionally he would walk out of the forest to see her.

Unsurprisingly, the fighters left a trail, and before long they came under attack. Khadushkaev says Russian Federal troops targeted them with artillery, planes and helicopters.

They moved on, and dug a more secure bunker - with kitchen and toilet - close to Khadushkaev's village. It was last winter that he thought about leaving. "But I had no way to leave without compromising my fellow fighters. It was only just now that I had to leave."

I asked him what that opportunity was. Khadushkaev's level tone doesn't change as he says, simply: "All the guys who were with me got killed."

After a pause, I invite him to expand. "It all happened in Khasavyurt (the town where we are talking)," he says. "Three of the fighters attacked some security officers, probably from the FSB (the Russian security service), and got killed. And the other three were killed in a car the same evening in Khasavyurt. They were shot."

Khadushkaev says he was not with either group "simply because that morning we went different ways. It just happened like that."

He decided to walk home and turn himself in as: "I didn't have blood on my hands." It may have helped Khadushkaev that he comes from a distinguished local family, and that - while the majority of militants only wind up leaving the forest dead, seriously wounded, or serving long prison terms - the security forces are also beginning to allow a small number of forest fighters to accept a travel ban and re-integrate into society.

It is a programme being overseen, from his large quilted-leather office chair, by Ramazan Jafarov, Dagestan's deputy prime minister. He is the point man for security in the republic, and a former general in the Russian army. Jafarov says, under his trim military moustache, that so far this year: "75 terrorists have been killed, 90 detained and 25 rehabilitated." There are, he says, 120 active insurgents left.

He does allow, though, that their number is being constantly replenished. As he wryly points out, three years ago, before he joined the administration, the then president of Dagestan was talking about there being "150 militants".

The deputy prime minister is under pressure to succeed. In under a year, the city of Sochi, on the other side of the Russian Caucasus, will host the Winter Olympics. "For us," Jafarov says candidly, "Sochi is a political event rather than a sporting event." He promises - boldly - that "terrorist activity will be brought to a halt by the time of the Games".

Speaking of the Boston bombing, it is, he says, "unfortunate" that something has to be blown up in the US "for people to pay attention to Dagestan". "Some parts of the international community think the gunmen here are freedom fighters - but when a bomb goes off in America or London, it's international terrorism," he adds.

Along with the rehabilitation programme for former fighters, Ramazan Jafarov also oversees the heavy force which the regional and federal security forces use against those involved in or suspected of militant activity.

Zuleikha Karnaeva's house was destroyed by security forces

Two days before, I had stood in the ruins of a house in the small town of Buynaksk. The owner, Zuleikha Karnaeva, was used to the fortnightly searches of her home by the security services. They had been coming for the two years since her now 18-year-old son, Khan, joined the fighters in the forest. Last month, though, she was told to clear out of her house, taking her valuables with her. Her neighbours were evacuated too.

As she stood on a nearby road, she knew what awaited. Minutes later, an explosion ripped across the quiet surrounding streets, many of which had been named after the great men of Russian letters. Karnaeva happened to live on Dostoyevsky Street, a tribute to the author of Crime and Punishment.

Her alleged crime, she found out later, was the one always used by the authorities. She had been "storing explosives", which could only be safely discharged on site.

Zuleikha Karnaeva's son Khan

The facade of her house has been re-plastered. But the inside is still strewn with rubble, glass and thick splinters of wood. Walls have disappeared. Window frames hang drunkenly. Karnaeva's husband has been taken in to custody. Of her son, all she has left are two photos which the security forces say they found on a memory stick at a forest encampment. As Karnaeva contemplates the ruins of her life as well as her house, she wraps her headscarf around her face to staunch the flow of tears.

In his high-ceilinged office in Makhachkala, Deputy Prime Minister Ramazan Jafarov bridles at the suggestion that such tactics are anything other than safe and proportionate.

And he draws a comparison with the scale and force deployed by the US authorities against the main suspects in the Boston bombings.

"I must say it was impressive," says Jafarov. "They liquidated one, and disabled the other."

Tim Franks' reports from Dagestan can be heard on the BBC World Service programme Newshour on 24 and 25 June.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter , externaland on Facebook, external.