English wine: Is sparkling wine better in England than France?

- Published

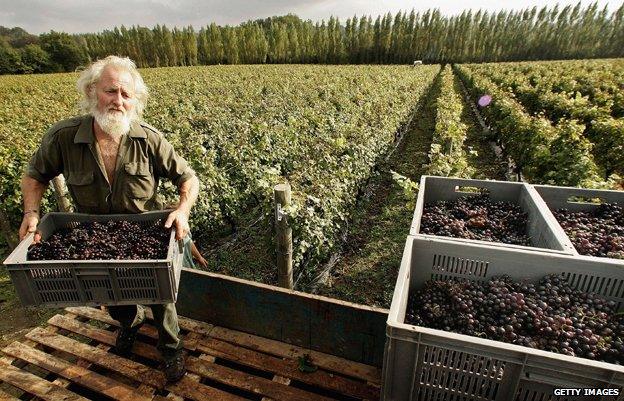

A vineyard in Hampshire

The Duchess of Cornwall has called for a new name for English sparkling wine to match the grandeur of champagne. And for the first time, domestic wine is the most popular in the government's cellar. Have Britons developed a taste for a home-grown tipple?

Someone arrives with a bottle of English wine. Cue excitable voices saying, "Gosh, English wine is really quite good, you know - it gives champagne a run for its money."

The surprise used to be palpable.

But English wine has grown up. Today it regularly wins awards - there were four gold medals at the International Wine Challenge (IWC) this year.

It's a far cry from English actor Peter Ustinov's put down: "I imagine hell like this - Italian punctuality, German humour and English wine."

But is there something holding English wine back? It accounts for just 0.25% of total wine sales in the UK, according to industry body English Wine Producers.

This week the Duchess of Cornwall called on producers to come up with a name. , external

"People should put their heads together and think of a new name for English sparkling wine," she said while visiting Hambledon Vineyard in Hampshire. "It should be something with much more depth. I plan to find a new word for it."

So is new terminology the final piece in the jigsaw?

English wine has been through a revolution. Old grape varieties are out, new owners are in. The area of vines planted in England and Wales has doubled from 761 hectares in 2004 to about 1,500 hectares today. The country now has 434 vineyards.

Figures just released by the Foreign Office on the government's wine cellar, show that for the first time more English wine was drunk at government hospitality events than wine from any other nation.

Andrew Neather, Evening Standard wine critic, says the new winemakers tend to be go-ahead types from the City or wealthy lawyers, who want to carve out another career.

They are focusing on sparkling wine, planting more of the traditional champagne grapes - chardonnay, pinot noir and pinot meunier. In 2010, for the first time more than half of the vintage went into sparkling wine.

Three of this year's four IWC gold medal winners were sparkling wines. In June, Majestic announced, external that sales of English sparkling wine trebled in 2012, encouraged by the Jubilee and Olympics.

There is logic to England focusing on fizz. Kent and West Sussex, where the best English sparkling wine originates, are only about 90 miles north of Champagne. The chalky soils around the North and South Downs are very similar to the earth where famous names such as Bollinger and Dom Perignon plant their grapes.

English vineyards

Chapel Down Winery in Kent

Harvested pinot meunier grapes at Nyetimber Vineyard in West Chiltington, West Sussex

Denbies Wine Estate in Dorking, Surrey, is the UK's largest single vineyard

Welland Valley Vineyard in Northamptonshire

Leventhorpe Vineyard in Leeds claims to be the longest established commercial vineyard in Yorkshire

The best English sparking wine is as good as "decent" champagne, Neather says. England's top seller - Nyetimber - has more to offer than a mass market champagne like Moet Imperial, he argues.

"It's more interesting, has more complexity and better acidity." The Moet costs more at £32.99 - although it is sometimes discounted - while Nyetimber is £29.99.

The Financial Times wine critic, Jancis Robinson agrees, albeit with a couple of caveats.

"Most English fizz is now very well made and attractively dry and zesty. But very little has any real complexity since producers generally cannot afford to age it very long." And cost is a problem. "It's never a bargain," Robinson says.

"It is generally made by people who have invested a great deal in new vineyards or winemaking and need to see a return."

The competition can be significantly cheaper whether prosecco, cava or own-brand champagne. Aldi, for example, sells champagne for just £12.99, external.

Despite the cost premium, patriotism and the fashion for local provenance suggests that current levels of production are outstripped by demand.

"The industry sells everything it produces," says Julia Trustram Eve, spokeswoman for English Wine Producers. "Demand is exceeding supply."

Production is still tiny in international terms. Champagne alone produces more than 300 million bottles a year, compared with England's total annual wine production of about 3-4 million bottles. Tesco sells only three English wines. Waitrose stocks 57 but this still only accounts for 0.6% of the wine it sells.

But there is momentum building, and big name involvement. The Queen is planning to sell wine from vines at Windsor Great Park. And next year the Waitrose vineyard at Leckford, Hampshire, will put its first bottles on sale.

Frazer Thompson, chief executive at the Chapel Down vineyard in Kent, believes that English wine can grow quickly. Over the next decade, English producers should aim to move from today's 2% of the UK sparkling wine market to 10 or 15%, he says.

Such a prediction will raise eyebrows. But Thompson cites the rapid growth of Chapel Down, which was selling 25,000 bottles of its non-vintage Brut for £5.99 when he joined 12 years ago. Today it sells 200,000 bottles at £18.99.

Sparkling wine from the southern counties seems here to stay. But English still wine divides the experts. "I have had credible chardonnay in this country but it tends to have so much acidity that it's better in sparkling wine," says Neather.

As a result of its lack of sunshine, the first English growers traditionally planted fast-ripening varieties like sevyal blanc, bacchus, and muller-thurgau. It's a problem, he believes.

"You're never going to make decent wine from muller or bacchus. They're just rubbish."

Julia Stafford, owner of Wine Pantry - two London shops selling exclusively English wine - disagrees. Part of English wine's charm is not just the success of its sparklers but its distinctive local grapes. "Bacchus hasn't got sauvignon blanc tropical fruits," Stafford says. "Instead it's like licking a Constable painting. You can smell the hedge rows and taste the English countryside."

Stafford conjures up an English wine vocabulary that might appeal to the Duchess of Cornwall. Up to now the language of wine - Champagne, terroir, vin de table, appellation controlee, premier cru - has been French.

The owners of Coates and Seely vineyard in the North Hampshire Downs have pushed the "Britagne" badge for sparkling wine.

"It is a brand which belongs to Coates and Seely, which we use for our own wine, and which we will invite other vineyards working closely with us to use," says Christian Seely. "It is definitely not intended as a generic term for all English sparkling wines." So Camilla's search for the right term goes on.

But language is not the real problem for English wine, Neather says. The big hurdle, even with climate change, is the weather. Last year Nyetimber ditched its entire harvest after a terrible summer.

"This is the big challenge of the English climate - getting the damned grapes to ripen," he says.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external