The unbearable sadness of the Welsh valleys

- Published

- comments

Many parts of the UK have suffered from the decline of heavy industry, but the Welsh valleys are a grim emblem of the despair that lack of work can create, writes Mark Easton for The Editors, a programme which sets out to ask challenging questions.

It is a journey I have been meaning to make for years. To Blaenau Gwent in the valleys of South Wales. To proud old colliery towns like Cwm, stretched out along the River Ebbw.

From the window of the bus snaking up the valley road, one is struck by how the rich joyous beauty of the landscape contrasts with the poverty and melancholy of the people who scratch out a living in these parts.

The numbers tell a long and sad story of decline. "We are top of every league you don't want to be top of," a man tells me. Poverty, sickness, worklessness - Blaenau's name is always among the worst.

The main street in Cwm is arrow straight. At one end is a chapel, now closed and daubed with crude graffiti.

Many of the people of Blaenau appear to have given up on God. A decade ago less than a quarter of people here said they had no religion - now the census shows it is over 40%.

At the other end of the street is a vast flat space - empty, save for two iron wheels buried in the ground. Even weeds don't grow here.

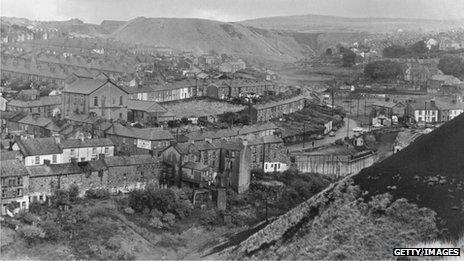

A century ago, 2,400 men worked at the Marine Colliery. The miners and their families had come to the valleys from hundreds of miles around - some had literally walked to the valleys, drawn by the prospect of employment.

All that remains are silent industrial gravestones. Among the terraces that once housed the workers are numerous boarded up shops and clubs. The town, like the mine, feels abandoned.

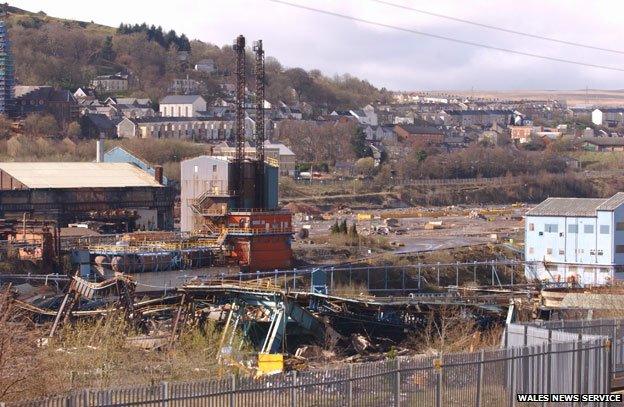

The story of Cwm is the story of these valleys. When the site of the former Ebbw Vale Steel Iron and Coal company was finally flattened in 2002, the reason communities settled here was extinguished.

And no-one has ever come up with a viable Plan B.

Why 'valley boys' have not given up on Welsh community

Politicians of many different stripes have held out the prospect of regeneration and transformation over the decades. But the promises have too often proved to be empty. "They kick us and then they kick us again," a local despairs.

Take the town of Blaina - a once thriving industrial community, now dying. "If it's not closing down, it's already closed," says Anita Banks, a local councillor.

She shows me the Blaina Action Plan, agreed a couple of years ago after a long consultation. It is full of high priority schemes to improve the town, but a walk down the High Street reveals that almost nothing has happened. The county council tells me funding has still to be agreed.

One of the plan's urgent priorities was "to create artwork on hoardings to brighten up boarded shops". A metaphor perhaps.

Shuttered shops in Blaina

And even that hasn't been done.

There have been many grand schemes for the county and millions have been spent on new roads and other infrastructure projects. But the one vital ingredient, the single commodity the people need more than anything else, has failed to materialise. Work.

"The jobs simply aren't here," says a man nursing a pint in an almost deserted working men's club. "But try telling that to the people at the top and they just don't want to know," he concludes bitterly.

A quarter of working-age adults are on benefits - male unemployment is more than double the British average. Among the economically inactive, the students and the homemakers and the sick, a far higher proportion in Blaenau Gwent say they would like employment than across the country as a whole. These communities are desperate for work.

Official figures show that last year more than 8,000 people wanted a job. But there were just 300 vacancies. And most of those were low wage temporary positions.

The Blaenau Gwent Regeneration Programme was published in 2002 after the closure of the steelworks in Ebbw Vale with much fanfare and razzamatazz.

Ebbw Vale in 1966

But more than a decade later and the targets on jobs and skills still remain unfulfilled. Indeed, just a few weeks ago the Wales Audit Office ranked Blaenau Gwent the least attractive place in the UK for inward investment.

There is a new hospital and a college on the giant scar that was the steel complex in Ebbw Vale. A new leisure centre is almost complete. But where once 14,000 men earned their living each day, precious few actual jobs have been created.

These are communities marooned when the economic tide went out.

Good people have tried to rescue them. The Ebbw Vale Development Trust has offered "economic and social regeneration". But the organisation has itself recently gone out of business. A number of people were made redundant at short notice.

A local employment scheme called JobMatch was hailed as the new hope for the valleys only a couple of years ago. But this JobMatch, it turns out, is now also out of a job.

"Why don't you leave?" I ask some unemployed men in their 50s. "Because we are valley boys," comes the reply. "This is home." The green, green grass…

And where would they go? Often with few if any qualifications and no savings, the idea of leaving family and friends for somewhere unknown, without a place to live and no guarantee of employment, does look ill-advised.

Resilience is failing.

There are fewer than 60,000 adults in Blaenau Gwent. Each month almost 10,000 prescriptions are issued for anti-depressants. It is a statistic so shocking it is hard to comprehend.

Blaina, a once thriving industrial community

At a drop-in centre run by the mental health charity Mind in Brynmawr, I meet Bev. She has been on anti-depressants for 15 years. "I can come here for a cry," she tells me.

Janice first started taking pills for her nerves almost 40 years ago. "When you haven't got the money to go out and even if you could you haven't got the bus fare to go anywhere, the depression sets in," she says.

The suicide rate in Wales increased by 30% between 2009 and 2011.

The further you go up the valley, the poorer and more isolated people become. Waundeg is at the very top.

There are no shops in Waundeg and the bus to town stops at 6pm. There are children who've never been more than a mile or two from their front door.

When I ask how many youngsters go to university from the estate, Diane tells me that she remembers someone going to college to do hairdressing. "No, I can't think of anyone who has been to university," she tells me. Diane has lived in Waundeg for more than half a century.

Poverty is endemic. One nearby school keeps a box of shoes for children who arrive without anything suitable on their feet.

In 1938 schools provided donated shoes - as they do today in the valleys

When a charity van delivers food boxes, people rush from their houses. "They hear the van and they all come out," Ceri tells me, surrounded by piles of donated food aid. "All this will be gone in an hour."

The boxes contain cereals, biscuits and baby food. "Some of the adults eat the baby food when it gets really tough," Ceri confides.

"Two please!" says Ray, in the queue for a box. "One for me and one for my brother."

"Do you really need these?" I ask. "I couldn't get by without them," he says.

It is the women of Waundeg who are fighting back. They have managed to secure an empty house as a community centre and are doing what they can to counter the deprivation.

"Quite a few of the kids were telling us they were just having bread and jam when they got home from school," Diane says. "So we set up a grub club to give them a hot meal."

The centre is overflowing with young children and community spirit. But one cannot help but feeling it as a fight against the odds.

In one room at the centre there is a bank of computers, donated by a project a few years ago. The idea was to give schoolchildren and their families vital access to the web. But the computers are no longer connected to the internet. The money ran out 18 months ago.

The plan is to host motorsports at the Circuit of Wales

Above Waundeg, on the moorland that borders the Brecon Beacons, is the site of what is being described as "the last hope for the valleys". The idea is to build a racetrack - the Circuit of Wales - creating thousands of jobs.

Planning permission for the project may be given in the next few weeks - but people are trying not to get too excited.

They remember the big electronics factory scheme that promised 6,000 jobs a few years ago. Today the complex employs 38 people - and half of those are security guards. They remember the countless projects and initiatives that came and then went. The action plans with no action.

I fear they are close to exhausting the once thick seams of hope that supported these beautiful valleys.

BBC News: The Editors features the BBC's on-air specialists asking questions which reveal deeper truths about their areas of expertise. Catch up on BBC iPlayer or BBC World News.