10 things about extradition

- Published

The Edward Snowden affair shows how complicated the international web of extradition treaties is. Here are 10 quirks of the system.

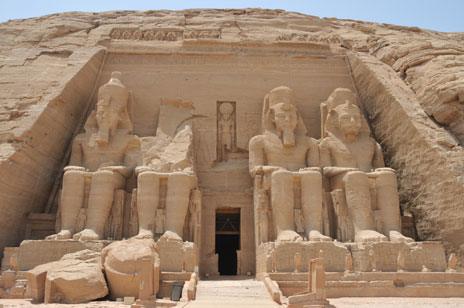

1. The world's oldest surviving written extradition agreement - and peace treaty - was made by Ramesses II of Egypt and the neighbouring Hittites in about 1259 BC. Sometimes known as the Treaty of Kadesh (following a battle there some years earlier), the agreement bound both sides to repatriate criminals and political refugees from the other side.

The temple of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel in Egypt

The Egyptian version of the treaty is preserved at Karnak. Its counterpart was discovered at Hattusa - site of the Hittite royal palace - in Turkey in 1916. A copy of that version now hangs on the walls of the UN headquarters in New York.

2. The first US extradition agreement was with Great Britain in 1794. It was not a full treaty but a single article in a broader treaty which sought to settle outstanding issues between the two countries that had been left unresolved since American independence. It only mentions the crimes of murder and forgery. The US's first modern treaty was signed with Ecuador in 1872, according to Douglas McNabb, an expert in US federal criminal law and international extradition.

Ecuador was co-signatory of the US's first extradition treaty

Early treaties often recite a "laundry list" of crimes, while modern ones tend to specify crimes that have a minimum sentence of a year in prison says McNabb. Early treaties such as those with Ecuador, Venezuela and Cuba include murder, assassination, piracy, mutiny and revolt, bigamy, counterfeiting and unlawful destruction of property such as railroads and bridges. Abortion was added in later updates.

3. Ingrained in most international extradition laws is the "political offence" exception, says McNabb. It allows the requested state to refuse extradition of those accused of political crimes or where that state believes the real motivation for the request is political rather than criminal.

The first British Extradition Act of 1870 declared that no-one could be surrendered if their offence was one of a political character. Many refugees fleeing Europe at the time - including Karl Marx - were offered shelter in the UK.

The European Convention on the Suppression of Terrorism (1977) limited the scope of the political offence exception.

4. The former reputation of parts of Spain as the Costa del Crime rested largely on the collapse of a 100-year-old treaty, which Benjamin Disraeli had a hand in negotiating. When it ran out in 1978, Spain did not hurry to renew it because it felt that it had not benefitted, with only a few extradition applications being accepted by the UK. "Spain uses civil law, and the UK has common law, and Spain didn't really understand how to make successful extradition treaty requests, which at that time required prima facie evidence, to the UK and so the relationship wasn't working," says Anand Doobay, an extradition expert at law firm Peters & Peters. "So during this period, practically every criminal in the UK went to Spain." A new bilateral agreement was signed in 1985.

Life on the Costa del Crime, as portrayed in the film Sexy Beast

5. The revival of the extradition treaty with Spain forced criminals from the UK to look for somewhere else to hide. The self-styled Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) beckoned, being the closest place to the UK with no extradition treaty. Separated from the Republic of Cyprus, it is only recognised by Turkey. In 2012, the Serious Organised Crime Agency (Soca) said Northern Cyprus was emerging as a growing centre for fugitive criminals.

Asil Nadir was eventually sentenced to 10 years in jail in 2012

It was home to Asil Nadir for 17 years after he fled the UK while facing trial over the collapse of the company he headed, Polly Peck International. But recently, the authorities have been cooperating with British police to apprehend and deport suspected wrongdoers. Dubai also became a bolthole for British fugitives, but an extradition treaty signed between the UK and the United Arab Emirates in 2008 has made it less of a draw.

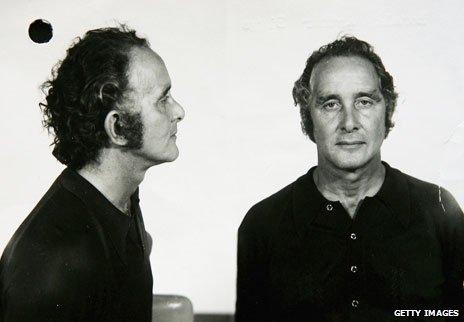

6. Brazil had no extradition treaty with the UK before the late 1990s, allowing Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs - who had escaped from Wandsworth Prison in 1965 - to enjoy the sun and sand of Rio for decades. Even if there had been a reciprocal treaty, Brazilian law prohibits the father of a Brazilian child from being extradited. In 1981, Biggs was kidnapped in Rio by a group of former British soldiers working for a security firm and ended up in the Bahamas, where it was hoped the government would extradite him to the UK. The country's high court, however, sent him back to Brazil. In 1997, Brazil and the UK signed a treaty, but Brazil still rejected a request to extradite Biggs. They also cited a statute of limitations that discounted crimes committed more than two decades previously.

Police mug shots of Ronald Biggs

7. Many countries will not extradite their own citizens to stand trial - some have this enshrined in their constitutions. Russia, for example, argued that its constitution prohibited it from extraditing Andrei Lugovoi, wanted for the poisoning of dissident Alexander Litvinenko in London in 2006.

Germany also has a very strong constitutional law. If a court feels the request is not proportionate - perhaps being for a minor offence - the Constitutional Court can block the extradition, says Jodie Blackstock, director of criminal and EU justice policy at charity Justice. "The Netherlands also usually seeks to request that a national accused of crimes committed abroad is tried, or serves a sentence, in the Netherlands," she says.

France has provided refuge to director Roman Polanski, wanted by the US after fleeing before he could be sentenced for having sex with a minor in 1977, because of his French citizenship,.

Former counter-culture leader Ira Einhorn - who was convicted in the US in absentia for the murder of his girlfriend in 1977 - enjoyed the protection of the French legal system for a number of years, not because of French citizenship, but because France holds that trial in absentia is an abuse of human rights.

8. The UK is a "bit unique" in not making the protection of nationals from extradition a feature of UK law, says Blackstock.

"I think it goes back to empire days when Britons were regularly travelling everywhere and establishing new lives.

"But even now, with the European Arrest Warrant in place, and where there is a provision in the EU framework decision that member states can seek for criminals to serve the sentence in their own country, we haven't transcribed that into UK law," she says.

9. Embassies have long given refuge to those fighting extradition. Under international law, diplomatic posts are considered the territory of the foreign nation. But authorities take different views on this. When Julian Assange took refuge in Ecuador's embassy a year ago, the British government considered invoking the Diplomatic and Consular Premises Act (1987) allowing for the revocation of a building's diplomatic status if the foreign power occupying it "ceases to use land for the purposes of its mission or exclusively for the purposes of a consular post".

"Diplomatic immunity exists to allow embassies and diplomats to exercise proper diplomatic functions and the harbouring of alleged criminals, or frustrating the due legal process in a country, is not a permitted function," William Hague said at the time.

"Seeking asylum within an embassy - like Assange has done - is much more prevalent within South America, where there are agreements between governments which recognise this. If a Peruvian opposition leader unsuccessfully attempts to overthrow the government then they can go to the Colombian embassy in Peru and seek asylum, for example. It's much more common and recognised, whereas the UK government has never recognised the principle that you can grant asylum in an embassy," says Doobay.

10. Xenophobia and illicit trafficking in hormonal substances are among the categories of offences a European Arrest Warrant (EAW) can be sought for which do not require the conduct to be a crime in the country receiving the EAW. The system, which has been in effect since 2004, was designed to simplify extradition procedures and has been signed up to by the 27 EU member states.

Other offences on the list of 32 include terrorism, trafficking in human beings, corruption and fraud, murder, kidnapping and hostage-taking.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external