Viewpoint: Could one man have shortened the Vietnam War?

- Published

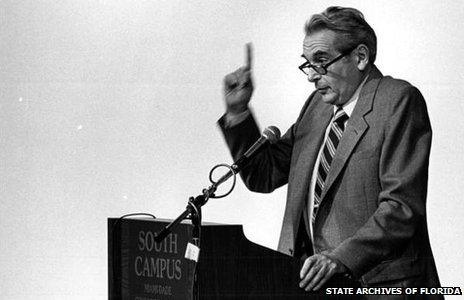

Konrad Kellen was an unknown defence analyst who might have changed the course of the Vietnam War if only people had listened to him, argues Malcolm Gladwell.

Listening well is a gift. The ability to hear what someone says and not filter it through your own biases is an instinctive ability similar to having a photographic memory.

And I think we have a great deal of trouble with people who have this gift. There is something about all of us that likes the fact that what we hear is filtered through someone's biases.

There are many examples of this phenomenon, but I want to focus on the story of Konrad Kellen, a truly great listener.

During the Vietnam War, he heard something that should have changed the course of history. Only it didn't. And today no-one really knows who Kellen was - which is a shame because his statue should be in the middle of the Vietnam Memorial in Washington DC.

Kellen was born in 1913. His full name was Katzenellenbogen - one of the great Jewish families of Europe. They lived in splendour near Berlin's Tiergarten. His father was a prominent industrialist and his stepmother was painted by Renoir, a family friend.

Kellen was tall, handsome and charismatic. He loved Ferraris. He could quote long sections of Thucydides from memory. One of his cousins was the great economist Albert O Hirshman. Another was Albert Einstein.

He lived one of those extraordinary 20th Century lives. When he was quite young, he left Berlin and moved to Paris where he became friends with Jean Cocteau. On a ship, the America, he was offered a job by the gangster Dutch Schultz. And when he got to the US, he met the author Thomas Mann and became his private secretary. Then he joined the US Army during World War II.

After the war was over, a young woman came up to him in a Paris cafe and asked if he'd do her a favour: "My father is an artist and I need someone to take his work back to America." He agreed. The woman was Marc Chagall's daughter.

Kellen was the kind of person that people went up to unannounced in cafes and asked great favours of. He had that gift.

After the war, the army sent him back to Berlin where his job was to interview German soldiers to find out why they kept fighting for Hitler long after it was clear that the war was lost. Then he went to work for Radio Free Europe. Again he had the job of a listener, asked to interview defectors from behind the Iron Curtain to get a flavour of what life was like under the Soviet regime.

And finally, in the early 1960s, he joined the Rand Corporation, a prestigious think tank in California started by the Pentagon after the war to do top-level defence analysis. And there he faced the greatest challenge of his career - the Vietnam Motivation and Morale Project.

The morale project was started by Leon Goure, who was also an immigrant. His parents were Mensheviks. They escaped from the Soviet Union during one of Stalin's purges. Goure was brilliant, charismatic, incredibly charming and absolutely ruthless, and he was Kellen's great nemesis.

The morale project grew out of the Pentagon's great problem in the early part of the Vietnam War. The US Air Force was bombing North Vietnam because they wanted to stop the North Vietnamese communists from supporting the insurgency in South Vietnam led by the Viet Cong.

The idea was to break the will of the North Vietnamese. But the Pentagon didn't know anything about the North Vietnamese. They knew nothing about Vietnamese culture, Vietnamese history, Vietnamese language. It was just this little speck in the world, in their view.

How do you know that you're breaking the will of a country if you know nothing about the country? So Goure's job was to figure out what the North Vietnamese were thinking.

He came into Saigon and took over an old French villa on Rue Pasteur in the old part of the city. He hired Vietnamese interviewers and sent them out into the countryside.

The job was to find captured Viet Cong guerrillas and to interview them. Over the next few years, they came up with 61,000 pages of transcripts. Those transcripts were translated into English and summarised and analysed.

Leon Goure was Kellen's greatest nemesis

Goure took those analyses and he gave briefings to all the top military brass in the American military establishment. And every time he gave a presentation on the Vietnam Motivation and Morale Project, he said the same things:

that the Vietcong were utterly demoralised

that they were about to give up

that if pushed a little bit more, if bombed just a little bit more, they'll throw up their hands in despair and run screaming back to Hanoi

It's hard to overestimate just how seriously Goure was taken in those years. He was the only man who understood the mind of the enemy. When dignitaries came to Saigon, their first stop would be the villa in Rue Pasteur, where Goure would hold forth at cocktail parties with insights into this strange, mysterious enemy they were fighting.

He'd be picked up by helicopter and whisked to aircraft carriers off the coast of Vietnam, so he could brief the top military brass who had flown in from Washington. They used to say that Lyndon Johnson would walk around with a copy of Goure's findings in his back pocket. What Goure said formed the justification for US policy in Vietnam.

Everyone believed what Goure said, with one exception - Konrad Kellen. He read the same interviews and reached the exact opposite conclusion.

Years later, he would say that his rethinking began with one memorable interview with a senior Vietcong captain. He was asked very early in the interview if he thought the Vietcong could win the war, and he said no.

But pages later, he was asked if he thought that the US could win the war, and he said no.

The second answer profoundly changes the meaning of the first. He didn't think in terms of winning or losing at all, which is a very different proposition. An enemy who is indifferent to the outcome of a battle is the most dangerous enemy of all.

Now why did Kellen see this and Goure did not? Because Goure didn't have the gift.

Goure was someone who filtered what he heard through his own biases. His biases were that this was 1965. The US was the most powerful country in the history of the world. North Vietnam was a speck that had barely entered the Industrial Revolution.

In just the first bombing campaign of the war, Operation Rolling Thunder, the US dropped as many bombs on this tiny speck as the RAF dropped on all of Germany throughout WWII.

Goure looked at the numbers and he could not believe that anyone could stand up in the face of that kind of assault. So he read that second sentence in the interview and he stopped listening.

Kellen was different. He had the gift. He was 20 when Hitler took over in Germany and he immediately packed his bags and didn't return until after the war was over. When asked why he left when he did, he would always say the same thing: "I had a feeling."

Hitler made it perfectly plain what his attitude towards the Jews was in those years, but most people didn't listen. Kellen did. That doesn't sound like a great accomplishment, but it was.

Listening is hard because the more you listen, the more unsettling the world becomes. It's a lot easier just to place your hands over your ears and not listen at all.

So Kellen stood up and said that Goure was wrong, that the Vietcong were not giving up and were not demoralised. It was not, he said, a battle the US could win - not today, not tomorrow and not the day after tomorrow.

Nothing happened. Goure had cocktail parties and entertained visiting dignitaries and helicopters whisked him off to aircraft carriers, and Kellen wrote long, detailed reports that were ignored and then forgotten. The war went on and things got worse and worse.

In 1968, a colleague of his went to see Henry Kissinger, who was then the incoming architect of the Vietnam War, and he urged Kissinger to meet Kellen.

But Kissinger never did. Maybe if he had, the course of history would be different. But that's the great irony of being a great listener. The better listener you are, the less people want to listen to you.

Kellen retired to a small cliff-top house overlooking the ocean in Los Angeles with a Chagall on the wall. He had a long and sad decline.

In his old age, he would wake up in the middle of the night and imagine that the Nazis were coming up the hill to get him. It was the only time he was ever wrong.

This piece is based on an edited transcript of Malcolm Gladwell: Listening in Vietnam on BBC Radio 4

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external