Viewpoint: Did our brains evolve to foolishly follow celebrities?

- Published

Our obsession with celebrity culture is a result of our poorly adapted brains, argues social anthropologist Jamie Tehrani.

I love a good quote.

One of my all-time favourite quotes comes from Mark Twain, who once wrote to his friend "I am sorry for the length of this letter, but I did not have the time to write a short one".

It's an apology I have often repeated in bloated ramblings to my friends and colleagues, and it's a wonderfully wry, pithy insight. Typical Twain, you might say.

Except that it's not. Because, as the person who recently pulled me up for using it told me, the true author of the quote is in fact a less well-known French thinker, Blaise Pascal, who coined it in a letter to a colleague in 1657. I looked it up and they were absolutely right.

And it turns out not to be the only quote I've been abusing.

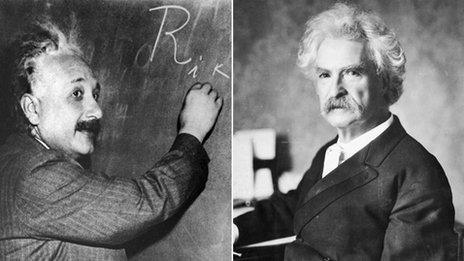

I'm sure most of you are familiar with Einstein's brilliant refrain: "The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result." It's probably the most famous thing he said, apart from "E=mc2".

Only, there's no record of him every having uttered these words. The first time they appeared in print was in 1981, in a Narcotics Anonymous pamphlet, some 25 years after the great man died.

There are many, many similar examples.

Winston Churchill, Benjamin Franklin and Martin Luther King have probably said less than half the things you've heard them quoted on. Because quotes are just so much more quotable when they come from individuals who are famed for their wit and wisdom.

It's OK. Because misattributing quotes exemplifies our tendency to give too much credit to celebrities.

Fame is a powerful cultural magnet. As a hyper-social species, we acquire the bulk of our knowledge, ideas and skills by copying from others, rather than through individual trial-and-error. However, we pay far more attention to the habits and behaviours demonstrated by famous people than those demonstrated by ordinary members of our community.

Good quote, wrong person: Albert Einstein and Mark Twain

It follows that things are much more likely to catch on if they are associated with someone who is well known for one reason or another - even if the association is erroneous, as in the case of those Twain and Einstein misquotations. This raises the question of whether what is said is as important as who said it.

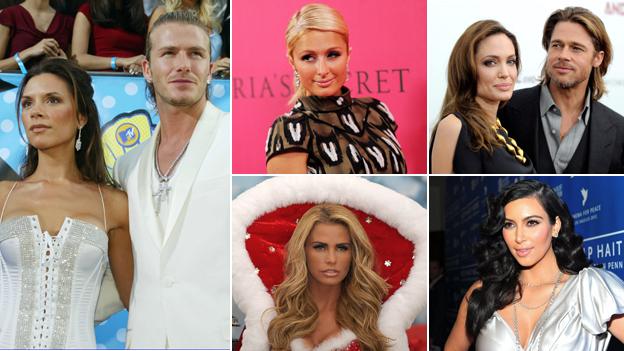

Another example of the way in which celebrities act as cultural magnets is that we frequently copy traits that have little, if anything, to do with what made them successful in the first place - like the clothes they wear, their hairstyles, or how they talk.

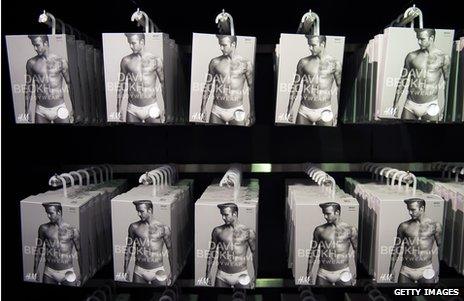

That's basically the reason that companies sponsor stars to use their products. Celebrities are always on the TV and in the media, so of course getting them to wear your brand of jeans or wristwatch is a great way to give them exposure.

But it's not just about getting your products in the public eye. You wouldn't know from images on TV or in a newspaper or on a computer screen what kind of underpants David Beckham wears, what coffee George Clooney drinks, or what perfume Beyonce smells of.

Companies get celebrities to advertise these kinds of products because they know that our perceptions of value are actively influenced by fame. Celebrity endorsements not only make products more visible, they make them more desirable.

So why is this? Celebrity culture is often portrayed as something relatively new, a product of a media-saturated but socially atomised society.

Although I agree that the form of celebrity culture has no doubt been shaped by the modern world, it is rooted in much more basic human instincts, which have played a key role in our acquisition of culture and have been crucial to the evolutionary success of our species.

We might focus on the anthropology of prestige. Prestige is a form of social status that is based on the respect and admiration of members of one's community. It is particularly interesting for anthropologists because it seems to be a unique characteristic of our species, and something that is universal to all human cultures.

Social hierarchies in other primates are typically based on dominance

In other primates, social hierarchies are typically based on dominance, which is different from prestige because it implies fear, and the threat of violence.

Individuals defer to more dominant animals because if they fail to let them have what they want then it would be perceived as a challenge to their status, which they will defend by force. Many types of hierarchy in human society are similarly characterised by dominance.

However, unlike other primates, we also differentiate social status in terms of prestige. In contrast to dominance, prestige is given voluntarily. It is freely conferred to individuals in recognition of their achievements in a particular field, and is not backed up by force.

How did such systems arise? The most convincing theory suggests that prestige evolved as part of a package of psychological adaptations for cultural learning. It allowed our ancestors to recognise and reward individuals with superior skills and knowledge, and learn from them.

This allowed new discoveries and techniques - for instance, how to exploit the medicinal properties of plants or optimise the design of hunting weapons - to spread across the whole population, and enabled each successive generation to build on and improve the knowledge of their predecessors.

Although the bias for preferentially imitating prestigious individuals has generally helped promote the spread of adaptive behaviours, anthropologists have suggested that it can make us susceptible to copying traits that are of no use in themselves, or which may even be harmful.

The reason for this is that prestige-biased learning is a very general strategy that is targeted at successful role models, rather than specific traits. This is precisely what makes it such a powerful and flexible tool - because the traits that make someone successful will vary significantly in different environments, so it makes sense to copy whoever happens to be doing best at a particular time and place.

However, because this strategy is somewhat indiscriminate, it can lead to people adopting all kinds of behaviours exhibited by a role model, including ones that have nothing to do with their success.

For example, men might observe a successful hunter perform some kind of incantation at the same time as he re-touches his arrowheads, and adopt both the ritual as well as his knapping techniques as a single package when they prepare their own tools.

This tendency, I believe, explains our interest in what sports stars and singers wear, what car they drive, and where they go shopping.

In the past any useless traits we acquired as a result of prestige-biased learning were offset by the benefits of picking up useful skills. So, in the long-run, it was an effective, adaptive strategy.

However, I am far from convinced that our attraction to prestige continues to promote superior cultural knowledge and skill.

The modern world is very different from the one in which our brains evolved, and I believe that the originally adaptive bias for imitating successful people has today morphed into an unhealthy obsession with celebrities, who we give far more attention to than they deserve.

Let me illustrate the point by way of an analogy to diet. We have an evolved preference for sweet-tasting and fatty foods because they motivated our ancestors to seek out ripe fruits and meat, which are rich in essential nutrients. But in today's world of mass-produced confectionery and intensive agriculture, these previously adaptive tastes have led to a massive obesity epidemic and all the health problems it's associated with.

Similarly, we can think of the mass-media as junk food for the mind. Quick. Convenient. But not exactly nutritious. We gorge ourselves on images of wealth and success because they appeal to our appetite for prestige. But are celebrities actually good role models?

Ancestral societies attached prestige to qualities such as hunting proficiency

In posing that question, I am not referring to well-publicised instances of bad behaviour by over-sexed footballers or drunken soap stars. I am talking on a more general level about the very purpose of celebrity itself.

In ancestral societies, the blueprint for a good role model was relatively well-defined - a good hunter, or gatherer, or parent, maybe a ritual expert.

But in our society, with its complex class system, division of labour and melting pot of cultures, the criteria for success are far more varied and opaque. Many celebrities have accomplished their success in fields like sport and music, which most of us have little hope of emulating.

But we still imitate what we can because our brains are programmed to associate prestige with adaptive behaviour. And because fame is the primary cue of prestige, the more attention celebrities get, the more they attract.

It's not surprising then, that fame has become an end in itself. Because in the modern world, it does not really matter what you are famous for.

Indeed, while celebrities today get more attention and prestige than at any other point in human history, we are frequently being told not to hold them up as role models.

But - seen from the evolutionary, anthropological perspective that I have sketched out - you may ask, what are celebrities for if they are not to be role models?

Why give them the benefits of our prestige, if it is not reciprocated with anything that might be of use to us?

In pondering those questions, we would do well to reflect on the words of Samuel Johnson: "To get a name is one of the few things that cannot be bought. It is the free gift of mankind, which must be deserved before it will be granted."

At least, I think that was Samuel Johnson.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external