Why China loves to build copycat towns

- Published

China is well known for its pirated DVDs and fake iPhones, but this "copycat culture" extends to architecture too - with whole towns sometimes replicated.

As you enter Thames Town, the honking and chaos of Chinese city life fall away.

There are no more street vendors selling steamed pork buns, and no more men hauling recyclables on tricycles.

The road starts to wind, and then, in the distance, you see what looks like a clock tower from a Cotswold village.

"It has this almost dreamlike quality of something European," says Tony Mackay, a British architect, and the master planner for the Thames Town housing scheme and the surrounding district of Songjiang.

When local officials hired Mackay in 2001, he found farms and ducks here.

Today, there are cobbled streets, pubs and half-timbered Tudor houses.

There's even a statue of Winston Churchill, and a medieval meeting hall that advertises chicken wings and beer in Chinese characters.

But Mackay is not happy. "It doesn't look quite right," he says. "It looks false."

More pictures of Thames Town, external

Mackay says the architects who took on the designs for the buildings created a pastiche, throwing together different styles, and abandoning authenticity.

Some of the half-timbered houses are six storeys high, for example, and the windows on the church just don't look right, he says.

"The proportions are wrong. The use of the different stones is all wrong. It would never be used like that in the genuine English church," he says.

The houses in Thames Town were largely bought as investment properties, so the town has always been quiet. It is only just beginning to develop a real sense of life and community.

To Mackay, the place looks like a film set. In fact, one Western blogger said it reminded him of the film, The Truman Show.

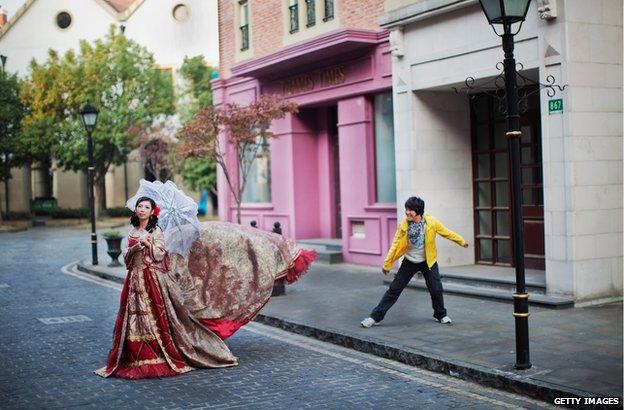

But Fan Yu Zhe couldn't care less.

I found Fan and his bride Sun Qi Yao looking deeply into each other's eyes as a photo assistant showered them with flower petals.

Thames Town is crawling with young couples who want to have their wedding photos taken here.

"I love European football, so I'm very interested in things from Europe," says Fan.

"I really hope I can visit the real Thames River one day, sit along the banks, drink a cup of coffee and enjoy the British sunshine."

Nearby, a woman named Zhang Li snacks on tangerines and plays cards with her mother and aunt.

Zhang says she has come here on her day off because Chinese towns are so crowded and commercial, but here it's green and pleasant. And as an office administrator, she can't afford to travel to England.

"Usually if you want to see foreign buildings, you have to go abroad," says Zhang. "But if we import them to China, people can save money while experiencing foreign-style architecture."

There's plenty of that in China.

Thames Town was built as part of Shanghai's "One City, Nine Towns" scheme, which saw a cluster of satellite towns built around the city, each in a different international style.

Elsewhere in China, there is a replica Eiffel Tower, a mock Tower Bridge - even a recreation of Stonehenge.

And last year, a replica of the entire Austrian alpine village of Hallstatt sprung up in the province of Guangdong. The original is a Unesco World Heritage site.

The world in China

Hallstatt #1 in Austria (l), and the replica of the village in China (r)

A mini Eiffel Tower in Beijing - there's also a replica in Hangzhou in Zhejiang province

France's baroque Chateau de Maisons-Laffitte recreated on the outside Beijing. France is a popular theme...

... As is Italy. You can take a trip on a gondola in China's very own version of Venice

The White House and US Capitol are popular choices for local government buildings

London's Tower Bridge - or near enough - has been transported to the city of Suzhou...

... And there's a copy of Stonehenge next to a new housing development in the east of China

These are all examples of China's craze for what Bianca Bosker, author of Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China, calls "duplitecture".

Of course, it's not just the Chinese who love to copy. A century and a half ago, the rapidly progressing United States was a hub of counterfeiting and copying, external and it too has a host of more recent architectural replicas, including country pavilions in Epcot in Florida, and plenty of examples in Las Vegas.

But according to Bosker, while many Westerners think of knock-off architecture as kitsch and bizarre, many in China find it truly lovely.

Almost every major city in China has a residential suburb where people live in replica mansions, and as many as two-thirds of the properties for sale with some estate agents are Western-style, she says.

Bosker says that's partly because China has a different attitude towards copying.

"The culture of copy in China is very different from what we find in the West, where there's a sense that copying is something incredibly taboo, and to be avoided at all costs."

In China, she says, mimicry is seen as "a form of mastery", and is therefore not frowned upon - but encouraged.

This culture of copying has deep historical roots. As China's first emperor, Qin Shi Huang - of terracotta army fame - conquered rival kingdoms in the 3rd Century BC, he built a replica of each of their palaces within his own capital city.

Fast forward to today and the Chinese government often bankrolls major copycat projects.

It's a way of flexing its muscles, says Bosker. "China is, in a very symbolic way, showing off its ability to rearrange the cosmos, to sort of own the greatest hits of the West."

It's no accident, says Bosker, that the White House - the ultimate symbol of US power - is one of the most copied buildings in China.

But not all Chinese people are supportive of this copycat architecture.

"I don't like them at all," says Tong Ming, a Shanghai-based architect.

China has its own rich architectural heritage, says Tong, like the Classical Gardens of Suzhou, external, the Forbidden City, external in Beijing, and the country's traditional wooden buildings.

The Classical Gardens of Suzhou are a Unesco World Heritage site

Chinese people do value this history, he says, but, at a time of such rapid change, people find it more practical - and even comforting - to copy Western styles.

"I think it is quite a specific period of time - people cannot get accustomed to changing times.

"So it's quite understandable that they would follow something that they admire, or are familiar with from the mass media," says Tong.

"People want something with a quite clear identity. They couldn't find exactly what next, so they turn to something they are familiar with."

Tong thinks, in time, Chinese architecture will find its own path once again.

In the meantime, some new housing developments are creating Western-style architecture "with a Chinese skin", says Bosker - incorporating a Chinese garden layout, for example, or feng shui principles.

British architect Tony Mackay thinks China's imitation towns are a fad - a by-product of China's desire to connect with the world after decades of relative isolation - but he sees a new trend emerging.

"The younger generations here they don't want old-fashioned style, they want modernism. They want something new, which connects to their gear, their iPads, and their modern lifestyle," he says.

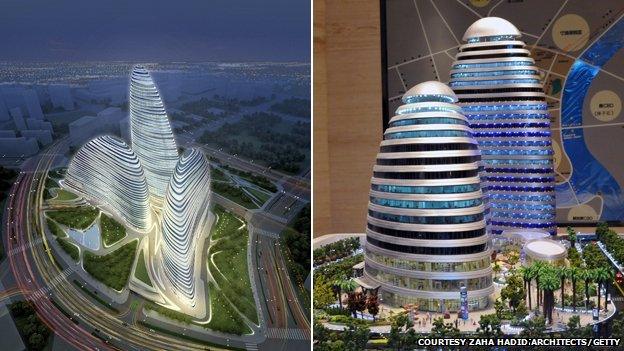

One example is the sleek, ultra-modern, prestige Wangjing SOHO project, external in Beijing, by British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid.

Plans for Wangjing SOHO in Beijing (l), and a model of a very similar building in Chongqing (r)

When it's finished, it will resemble three fish-like forms emerging from a stream.

There's just one problem. A suspiciously similar structure is being built in the city of Chongqing.

According to one industry publication, the alleged copy may be finished before the original.

Ruth Morris was reporting for The World, external, which is a co-production of the BBC World Service, PRI, external and WGBH, external

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external