Leaving Australia, a confounding and complex country

- Published

Australian television producers have in recent times hit upon a sure-fire formula to guarantee big ratings.

Costume designers are instructed to dress the women in above-the-knee skirts. Make-up artists affix Dennis Lillee-style moustaches - or "mos" - to their male leads. Props departments scour second-hand car yards in search of mint condition Ford Falcons and Holdens from the 1970s.

The fashion is for retrospective drama, whether it focuses on the "Puberty Blues" of teenagers coming of age in beachside suburbs, the publishing wars between media barons like Rupert Murdoch and Kerry Packer, or the birth of World Series cricket, the cradle of so much Australian sporting iconography. Why, even the cult series Prisoner Cell Block H has been revived!

A swathe of recent news stories, which have made headlines around the world, would also suggest that Australia itself has returned to the unreconstructed Seventies.

There was the Liberal party supporter who designed a spoof menu for a fund-raising dinner with its "Julia Gillard Kentucky Fried Quail - Small Breasts, Huge Thighs and a Big Red Box".

There was the disrespectful line of questioning that the then-prime minister endured from a Perth shock jock, who asked whether her partner was gay.

The Australian defence forces were hit by yet another sexual scandal, this time involving high-ranking military personnel who sent emails containing videos denigrating women.

Nor should we forget Eddie McGuire, a Melbourne celebrity who has made a career out of his chirpy Aussie blokiness. He joked that an Aboriginal footballer, who only a few days before had been racially vilified by a young football fan, should publicise the new King Kong stage show.

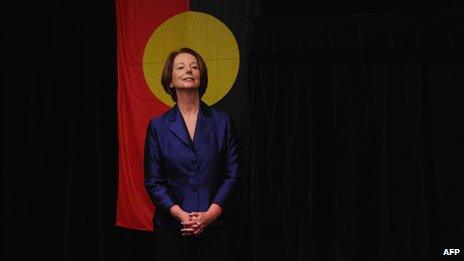

The axing this week of Julia Gillard, a female politician who shattered a ceiling made of particularly resilient glass, has raised a broader question: was Australia ready for a female prime minister? In my view, that question can ultimately be dealt with in one word: yes.

But you would not think it from the headlines of the past month. Unquestionably, Australia is often crassly stereotyped in the international media. Recently, however, it has been more a case of the country typecasting itself.

In many ways, then, my posting here has ended as it started. Back in September 2006, the national conversation centred on Steve "the Crocodile Hunter" Irwin, who within days of my arrival was killed by a stingray. In my final weeks, the discussion has focused on lesser-known figures, like that Perth shock jock Howard Sattler.

But the question has essentially remained the same: who gets to define and personify Australia?

My answer, of a country whose population has swelled to 22 million people while I have been here, would be everyone. For this is a land that defies neat encapsulation or lazy caricature.

Modern Australia is seen in the defence personnel who allegedly sent those venal emails, but also in the stirring words of their commander Lt Gen David Morrison, the head of the Australian army: "The standard you walk past is the standard you accept."

Eddie McGuire, that self-styled Australian everyman, is undoubtedly representative - but so, too, was his radio sidekick on the morning that he vilified the indigenous footballer, Adam Goodes, who refused to go along with the joke.

Howard Sattler may have a significant following, but he no longer has a job.

Australia is reflected in the columns of right-wing commentators, who tend to play down the uglier aspects of national life, and also those on the left, who are prone to excessive national self-recrimination.

You see its contradictions in offices and factories with polyglot workforces that look happily multicultural, but whose Asian workers might have got their jobs by disguising their surnames. You see it at the country's sports grounds, where a spirit of irreverent fun is often countered by the mind-numbing officiousness of administrators and stewards.

You witness it in the childishness of Canberra's parliamentary Question Time but also in the touching - and often teary - response from the chamber when departing MPs give their valedictory responses.

You see it at Australia's offshore detention centres, where young Australians implement an intentionally harsh policy with compassionate hearts. Earlier this month, I witnessed this for myself in Nauru, where the asylum seekers held in indefinite detention saw both sides of the country they embarked on such perilous journeys to reach.

On the boat people question, my sense is that Canberra politicians have an exaggerated sense of the xenophobia and racism within portions of the Australia electorate that drives their tough policies. For the most part, they also let those sentiments fester unchallenged.

Over the years, I have spent a lot of time in the western suburbs of Sydney. It is the most politically influential part of the country and one supposedly seething with hostility towards boat people.

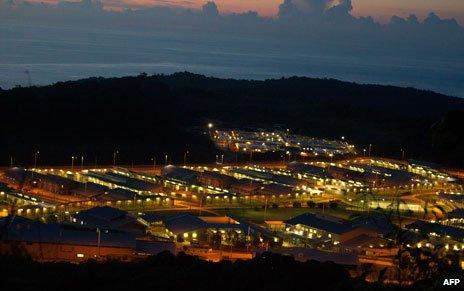

A detention centre for immigrants sprawls over Christmas Island

Usually when I have asked voters to list their concerns, however, they cite cost of living concerns and traffic congestion long before they mention asylum seekers. When I read commentary suggesting that border protection is the dominant issue in the minds of "ordinary Australians", it does not ring true.

One of the failings of politics in Australia in recent years is that politicians on both sides have allowed voters to conflate the asylum seeker problem with everyday worries. Some politicians, who demagogue this issue, actively encourage their scapegoating, even though 90% of boat people turn out to be bona fide refugees.

As if to emphasise the nation's split personality on the question of welcoming foreigners to its shores, Scott Morrison, the conservative opposition's tough-talking immigration spokesman, used to head up Tourism Australia.

On the cultural front, Australia is as much Cate as it is Kylie. It is the Aboriginal singer Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu as well as the crooner John Farnham. It is Baz Luhrman much more so than that the 1970s creation Bazza McKenzie.

The comedian Barry Humphries invented McKenzie, along with Dame Edna and Sir Les Patterson, to satirise what he saw as Australian "bigotry, dullness and boringness". They were characters of their time.

Of his time: Bazza McKenzie

But the comic genius Chris Lilley, of Summer Heights High fame, has more recently come up with a range of characters, from the camp schoolteacher "Mr G" to the Chinese physics prodigy Ricky Wong, who offer a much sharper and nuanced take on modern Australia.

My point, admittedly, is banal: that Australia is confounding and complex. But it is worth making again, because the rest of the world still has a tendency to regard the "land down under" as uncomplicated and unchanging.

The ousting of Julia Gillard offered a case in point. In the global rush to the judgment, the widespread assumption was that Australia remained an outpost of unreconstructed male chauvinism unwilling to countenance a female leader.

Yet as the outgoing prime minister herself put it: "The reaction to being the first female prime minister does not explain everything about my prime ministership, nor does it explain nothing about my prime ministership. It explains some things and it is for the nation to think in a sophisticated way about those shades of grey."

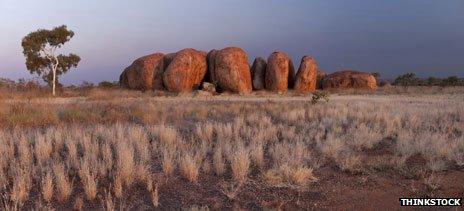

In a land of brilliant colour, from the red ochre of its outback to the aquamarine of its oceans, there are indeed countless shades of grey. And Australia deserves to be thought about in a sophisticated rather than stereotyped way.

I often think I have reported on Australia's rise and fall. Commercially, economically, culturally and diplomatically, it has never been taken more seriously. On the political front, however, it has become something of a laughing stock.

Outsiders look on its brutality and bloodiness - like a soap opera directed by Quentin Tarantino, I said of the latest leadership "spill" - and find it hard to fathom. Why so much political volatility in a country with so much economic stability?

But the national story, which tends to get judged globally in terms of gross domestic product, has been out of sync with the Canberra story, with its gross domestic politics.

My prime reason for coming here was personal rather than professional. I had fallen in love with an Australian. Since then, I have come to love Australia, too. Happily, that Sydneysider who brought me here is now my wife.

I am even more delighted to report that she is also the mother of our two beautiful children. So this is by no means a final farewell. Besides, I may be leaving, but I am taking my favourite Australians with me.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter , externaland on Facebook, external