WWI tourism: Looking for your family hero

- Published

As the 100th anniversary of WWI approaches, growing numbers are tracing their genealogy back to Europe's battlefields. Matthew Davis went to Ramicourt in France to find the spot where his great-grandfather won the Victoria Cross.

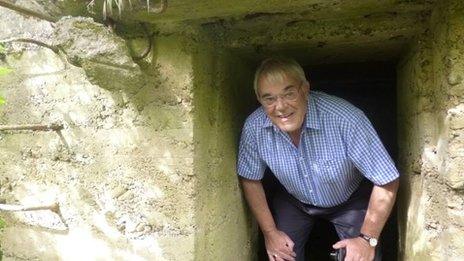

In mid-June 2013 my father, my brothers and I were standing in open countryside in northern France, in shorts, sun on our backs, plucking up courage to wade through a thicket of stinging nettles to where a crumbling concrete bunker lay half-buried at the edge of a cornfield.

Almost 100 years ago, my great-grandfather was on the same spot, under very different circumstances.

It was just after 06:00. Machine-gun fire replaced the sound of birdsong, and coils of barbed wire protected the German guns where Sgt William Henry Johnson was about to perform an astonishing act of courage.

Matthew Davis (left), and his great grandfather, William Henry Johnson

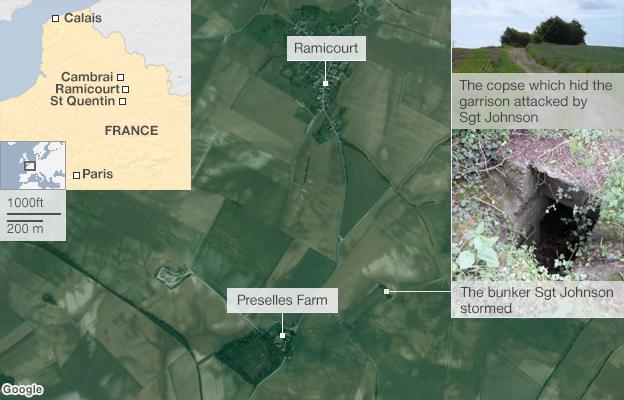

In October 1918, this area - around the village of Ramicourt - was the Beaurevoir-Fonsomme line, part of the Hindenburg Line system of trenches, fortified villages and gun emplacements that formed the last line of German defences on the Western Front.

On the morning of 3 October, the 1/5th Battalion, The Sherwood Foresters, with my great-grandfather as a platoon leader, was among a wave of Allied soldiers attacking German positions along the line, advancing behind a barrage of artillery fire.

What happened next, just north of Preselles Farm, which stood then and stands today, is best described by the plain but striking military citation from the commander of Britain's Fourth Army, who awarded Sgt Johnson the Victoria Cross:

"When his platoon was held up by a nest of enemy machine guns at very close range, Sergeant Johnson worked his way forward under very heavy fire, and single-handed charged the post, bayoneting several gunners and capturing two machine guns.

"During this attack he was severely wounded by a bomb, but continued to lead forward his men. Shortly afterwards the line was once more held up by machine guns. Again he rushed forward and attacked the post singlehanded. With wonderful courage he bombed the garrison, put the guns out of action, and captured the teams. He showed throughout the most exceptional gallantry and devotion to duty."

The probable site of the garrison post Sgt Johnson attacked is hidden by a copse of trees on high ground, a natural strong point with views across open ground that must have provided its gunners with clear sight of the advancing foot soldiers.

The citation hardly conveys what a terrifying prospect the position, and its supporting defensive bunkers, must have presented to the attackers.

Walking up from the farm, our chatter is about lines of fire, of which direction the platoon must have approached from, of where they may have sought cover as bullets whizzed about them, and how the landscape then must have been a world apart from the bucolic beauty of today's.

But as we reach the emplacement, we fall silent, reverential. Dug into a hollow on the brow of the hill, hidden in brambles and nettles, is a piece of family history.

Without maps of the area and a diagrammed account of the battle from the Nottingham & Nottinghamshire Victoria Cross Committee, external, we would have passed this by without a second glance. But now the dry military documents are brought to life and every detail of the scene has a potential story.

The iron rungs on the outside of the bunker are twisted and misshapen - was that damage from a bomb or a grenade? Did Sgt Johnson throw it there?

There are indentations - bullet holes perhaps - all over the concrete. Did he and his men fire those shots as they rushed up the slope?

Atop what appears to be a gun platform are rusting fragments of barbed wire - it must have been an evil thicket of the stuff on that day.

A second bunker lies within sight of the first, this one accessible only through a dark opening in the roof of the concrete structure. Dropping down inside is like stepping back in time.

On the floor, sticking up from the mud are the rusting paraphernalia of daily life in the field - a metal plate and bucket, a mug.

Did the occupants of this outpost drink a brew from that receptacle the night before their final morning? Did they hunker down in here as shells rained around them? What terror did they mete out from their firing point, and experience as their defences were overcome?

To one side is a bullet casing. Who fired it, at whom? And how deafening a place must this small hideout - protected yet vulnerable - have been as the sounds of battle raged.

Near the bullet casing there's another ominous object. It looks like a can with a wooden handle, almost like a grenade. We leave.

An emotional moment for one of Sgt Johnson's grandsons

Driving through the village of Ramicourt. By the side of the road is one of the war cemeteries that dot this landscape, kept pristine by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, external.

Rows of white headstones bear the names of young men who died on the same day that Sgt Johnson went into battle, many from the same area of England.

The sheer number of these graves are a reminder of the scale of the human suffering witnessed here, but also of the extent to which so many in the UK and beyond are still connected to the place today.

It is an area steeped in history. A few miles west at Joncourt, the war poet Wilfred Owen, external was killed in action, days before the Armistice. One of the most striking photographs of the war was taken by the nearby St Quentin Canal, where thousands of Allied troops posed on the steep banks by the Riqueval Bridge. Further west still lie the battlefields of the Somme, where more than a million men became casualties of one of humanity's bloodiest battles.

The Historial de la Grande Guerre, external museum at Peronne is at the centre of that region and is expecting an influx of visitors from 2014, as those with personal connections to the war are inspired by the looming 100th anniversary.

At nearby Thiepval, the largest British battle memorial in the world commemorates the 72,191 missing British and South African men who perished in the Somme with no known grave.

Steeped in history: Troops by Riqueval Bridge immortalised in one of the war's best-known photographs

The memorial is being renovated ahead of major ceremonies planned for 2014, and its visitor centre runs an ongoing project, external seeking information and photographs about the men named on the memorial itself.

Unlike those remembered at Thiepval, Sgt Johnson's story did not end on the battlefield.

Though wounded and suffering from influenza, he eventually made it home to Worksop, where his achievements were celebrated until his death in 1945, though he rarely spoke of the war.

While he was recuperating in France, one of the sisters in the hospital wrote to his wife to offer congratulations on her husband's honour:

"He has not told us by what act of special courage he won the distinction, and his modesty only enhances its value. We who have been with him through his long and trying illness can really appreciate the moral courage which goes to make up the true hero."

Being able to touch the scene where that act of courage was performed makes those words ring ever truer today.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published25 January 2012