Great Train Robbery: How Bruce Reynolds became a writer

- Published

It's nearly 50 years since the heist which became known as the Great Train Robbery. Novelist Jake Arnott got to know Bruce Reynolds - the leader of the gang - towards the end of his life.

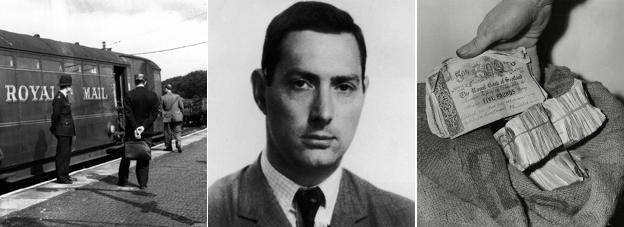

At 3am on 8 August 1963, the night mail train from Glasgow to Euston was stopped in Buckinghamshire by a gang of thieves. They broke into the High Value Package coach and made off with 120 mailbags stuffed with £2.6m in used banknotes (something in the region of £41m in today's money).

The raid soon became known as the Great Train Robbery and 50 years on it still occupies a unique place in the history of British crime. The gang carried no firearms, although the train driver was coshed in the melee - an act of violence that the leader of the gang, Bruce Reynolds, always expressed regret for, right up until his final interview.

I knew Bruce, and though he may be remembered for his life of crime, it was as a man of letters that he always impressed me.

His memoir, The Autobiography of a Thief, is an exceptional book, not simply because of the extraordinary life it documents but because it's so well written. And in person he had an artful way with words. When we first met, at a book reading 13 years ago, I was struck by his wit and erudition and by that literary knack of hoisting just the right allusion to illuminate a story.

Scene from 'The Great Train Robbery', BBC drama to be broadcast in 2013

Standing on Bridego Bridge awaiting his greatest coup, he saw himself as Lawrence of Arabia on the Hejaz railway, his ear to the ground listening for the oncoming train.

Calling on a tradition of adventurism he also conjured: "Visions of Drake and his motley crew at Panama, of Max, my old cell mate who had continually exhorted me: 'You've got to sack a city.'" I remember Bruce quoting William Burroughs, whose art manifesto "Les voleurs" declared: "Steal everything in sight, everything belongs to the inspired and dedicated thief."

He cut something of a Burroughsian figure himself. Gaunt and elegant with a laconic and deadpan delivery, a southern drawl to his voice - albeit of Battersea rather than St Louis. He was the true literary outlaw.

Bruce could evoke the glamour and excitement of crime as well as the heavy costs his way of life incurred.

His descriptions of the haute couture of an elite villain were so vivid that I was reminded of Daisy Buchanan bursting into tears at the beauty of Gatsby's shirts in F Scott Fitzgerald's great American novel. But he was direct and honest about his own failings and vulnerabilities, and never flinched from describing the ill effects of his activities on himself and those around him. His life and works were the perfect illustration of the old Spanish proverb: "Take what you want, then pay for it."

Born in 1931 in South London, Bruce had an unsettled childhood that was further disrupted by wartime evacuation. He left school at 14 and, having failed his eyesight test to join the Royal Navy, decided that he wanted to be a foreign correspondent. He even found the confidence to apply in person to Northcliffe House, home of the Daily Mail and Evening News. He ended up as a messenger boy and then in the accounts department.

He longed for adventure but reasoned that he was unlikely to find it in an honest living. So, unfortunately, he applied his intelligence and ingenuity to larceny, graduating from petty theft to more and more serious crimes.

Bruce Reynolds in 1963 (left); after his arrest in 1968 (right)

By the time he organised his most famous heist Bruce had become a major league villain and had created a character for himself out of his aspirations. Renting a villa in the south of France, driving fast cars and wearing exquisitely tailored clothes, he sought not just the trappings of wealth, but the sense of culture and entitlement that went with it. "I was the image that I created," he said of that time.

The Great Train Robbery took place in 1963, the "annus mirabilis" of Larkin's poem, "between the end of the Chatterley ban and the Beatles first LP" and right on the crest of a nascent social revolution.

It was also the year of the Profumo scandal and a sense that the new permissive society would need its ne plus ultra. The robbers had stolen the Queen's money, there was a feeling that the Establishment had been given a bloody nose and it duly lashed out. In the first trial, gang members were given 30-year sentences at a time when there was no parole system.

Bruce evaded capture for five years and went on the run, living the high life in Mexico with his wife Angela and young son Nick until the money ran out. Then he took the extremely risky decision to come back to England to plan another coup. The tenacious Scotland Yard detective Tommy Butler finally caught up with him in Torquay in 1968. Bruce was characteristically cavalier on his arrest, remarking: "C'est la vie, Tom."

Long-term imprisonment took its toll, however. The dull horror of incarceration, the pain of readjusting to the outside after a long sentence. He struggled to maintain and develop a strong relationship with his son Nick. And though their marriage broke down when he was in prison, Angela and Bruce were eventually reconciled. When she fell ill he committed himself to caring for her until her death in 2010.

And he became a writer. His own life was like a novel, but what was astonishing was his ability to set it down so clearly.

I believe that it was his love of words and his ability to use them that really set him free. Self-reflective, philosophical, for want of a better word, rehabilitated. When he came to my book launch a year ago we talked of the looming 50th anniversary of the Great Train Robbery.

He told me: "A lot of people are going to want to talk to me but I'm feeling a bit Greta Garbo about the whole thing, to tell you the truth." I wasn't sure he would agree to an interview.

When he came to the studio this January he was a little frail, he'd had a hard winter. But in front of the microphone he really went to work with his inimitable style. He talked for two hours. It was his final testament.

Bruce Reynolds, pictured in 2003

At the end he said: "I got what I wanted out of life, what I considered a good life. I wanted to live a life like Hemingway. When I was in Mexico the people I knew were bullfighters and motor racing drivers. But when you're in the position where you can do anything it no longer has the same attraction.

"You realise it's all tinsel to a degree. I only ever wanted to live in a place that I felt comfortable in, which, ironically I suppose, is about the size of a cell."

Radio 4's Archive On 4: The Crime of the Century is broadcast on 13 July, 20:00 BST

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

.