The arrival of women in the office

- Published

The typewriter is almost obsolete in the modern office. But it played a crucial role in women's arrival in the workplace, explains Lucy Kellaway.

In 1887, Rudyard Kipling met one of the new breed of typewriting girls while visiting San Francisco.

They aroused in him a mixture of fear and fascination, insisting that their work was enjoyable and their "natural fate" - that was until Kipling questioned further.

"Well, and after?" said I. "What happens?"

"We work for our bread."

"Till you die?"

"Ye-es, unless," said the partner in the firm audaciously, "sometimes we marry our employers - at least that's what the newspapers say."

The hand banged on half a dozen of the keys of the machine at once. "Yes, I don't care. I hate it, I hate it, I hate it!"

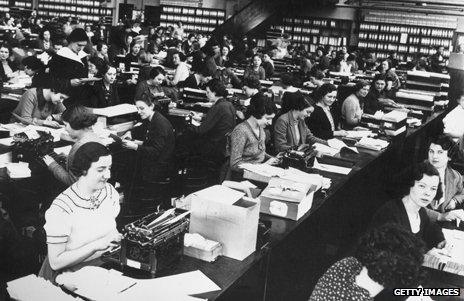

In offices today almost all the most boring tasks are done by women. At the photocopier, at the filing cabinet (or its digital equivalent) and on the reception desk - it's females only. So much so that when a few years ago I came across my first male PA I was almost as shocked as Kipling.

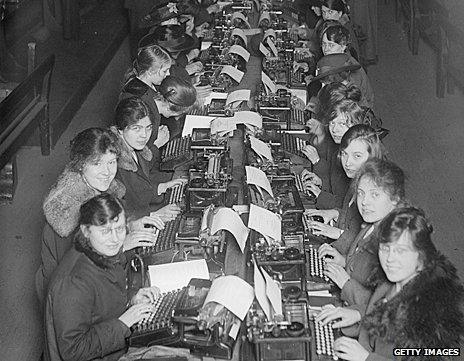

This feminisation of office work happened incredibly fast. Until the late 19th Century there were no women in offices at all. In 1870, there were barely a thousand of them. By 1911 there were 125,000 and by 1961 there were 1.8 million, in 2001 there were 2.5 million female clerks.

But how did it all begin?

A photograph taken in 1899 shows a young woman sitting on a desk, legs crossed with one foot on her chair. She's wearing a nice pair of shoes and there's a bike leaning against her desk. On the desk a half-eaten apple, a glass, a desk calendar, some files and... a Remington Standard 2 typewriter.

It's a pretty racy picture for the time - you might even be able to see a hint of her upper shin, never mind ankle.

But what it does show is a new type of working woman with the twin instruments of emancipation - the bicycle and, more importantly, the typewriter.

As the American Journal noted in 1898: "No expert can manage either the typewriter or the bicycle while she is held in a close-fitting cage of whalebone and steel."

The typewriter girl, like the typewriter itself, was an American export.

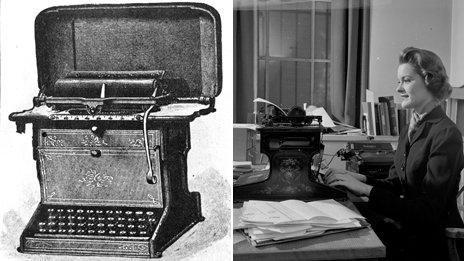

The first commercial typewriter was produced in 1873 by E Remington and Sons

The first machines with the Qwerty keyboard were triumphantly brought on to the market by the US gun-maker E Remington and Sons, in 1873. But far from being popular they were a total flop and probably would have stayed that way, had not some bright spark in the marketing department had the great idea of flogging them to women - to the daughters of middle-class businessmen.

"The typewriter is especially adapted to feminine fingers. They seem to be made for typewriting. The typewriting involves no hard labour and no more skill than playing the piano," wrote John Harrison, in his 1888 Manual of the Typewriter.

In the stores at the Museum of London are some early typewriters, including a very early Hammond model, which looks like a mahogany toilet seat.

"The major brand was the Remington," says Alex Werner, head of collections at the museum.

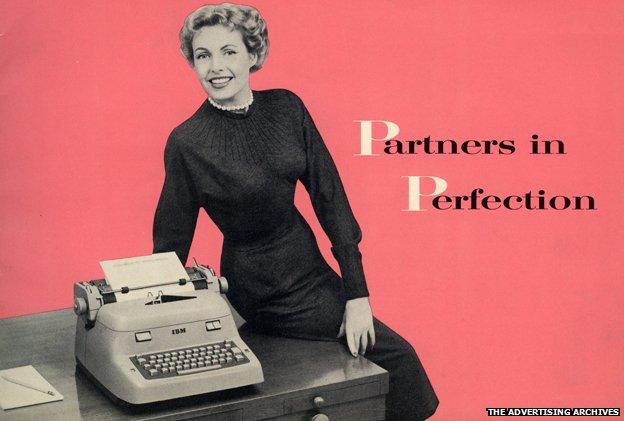

"They produced beautiful adverts with attractive women typing away."

The keys were made for dainty figures. My fingers, clad in plastic gloves, are too clumsy.

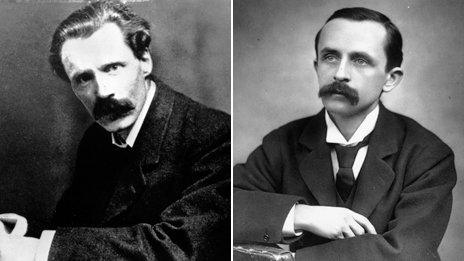

The typical typist was a liberated woman. Novelists and playwrights - George Gissing and JM Barrie - were fascinated by her, creating heroines who wore no-nonsense clothes, rode a bicycle, took up smoking and hung out with anarchists in the English countryside.

Writers George Gissing and JM Barrie were inspired by typical typists, who they saw as liberated women, often incorporating them into their work as heroines

A real life version of these pioneers was Janet Hogarth, who became the Bank of England's first ever female clerk in 1893.

She was a high flier in her day. She had achieved first class honours in philosophy from Oxford and was a skilled linguist. But her job was a boring one.

"It was monotonous, essentially dealing with cancelling bank notes, sorting them and crossing them off in the ledgers," says John Keyworth, curator of the Bank of England's museum.

Women were cheaper than men, and took over the jobs that were previously filled by young boys, who would have been supervised by an older man because it was so mind-bendingly boring.

"They gave her six months to learn the job," adds Keyworth. "She mastered it in a very short time."

Hogarth writes of it in her autobiography. "It was almost unbelievably soothing to sit in the quiet upper room with nothing to do but lay out banknotes in patterns like patience cards," she wrote.

"Learning all about the little marks on them, crossing them up in piles like card houses, sorting them in sixties and finally entering their numbers in beautiful ledgers made of the very best paper, as if intended to last out all ages."

In the late 19th Century it was inconceivable to have men working alongside typewriter girls, for fear of damage to their morals. Precisely how the damage was meant to occur, no-one was quite clear, but it was thought best to keep the sexes entirely separate.

So men and women had different entrances, different working hours, different dining rooms and often worked behind screens or in attics so that no man could see them.

An autobiography by a male employee at the Bank of England recalls how ridiculous it all was.

"The streets it was held were safe enough, but once she the woman clerk entered this forbidding fortress every imaginable horror was predicted," wrote the author.

But that wasn't all. So as to avoid the danger of typewriter girls on the loose, many employers refused to let them out during their lunch break. Women at the Post Office were not allowed a midday breath of fresh air until 1911 - and that was only after a kicking up a huge row and making personal appeals to the postmaster general.

So how did men feel about their new female colleagues?

The answer - predictably - was that they weren't happy at all. Part of the hostility was fair enough. The women were an endless source cheap competition. A particularly patronising piece was published in the Liverpool Echo in 1911:

"These intrepid typewriter pounders, instead of being allowed to gloat over love novels or do fancy crocheting during the time they are not 'pounding', should fill in their spare time washing out the offices and dusting same, which you will no doubt agree is more suited to their sex and maybe would give them a little practice and insight into the work they will be called up to do should they so far demean themselves as to marry one of the poor male clerks whose living they are doing their utmost to take out of his hands at the present time."

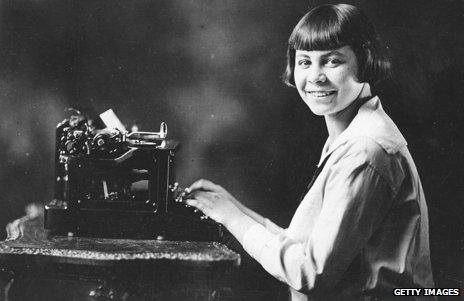

Birdie Reeve Kay, a champion typist capable of more than 200 words a minute

But actually the arrival of women in the office wasn't altogether bad for men. If they had working daughters - as many did - their households were better off. And as women were given the most tedious things to do, men's chances of promotion were higher. And then, of course, the women were easy on the eye and possible candidates for future wives and mistresses.

Meanwhile, at the Bank of England, the chief accountant, a Mr Stuchbury, was hard at work with his stopwatch calculating whether employing women was such a good idea after all.

He studied a question that has always interested me - are women more conscientious than men. His answer was much as I'd figured out for myself - yes.

He found that 37 women had counted as many notes as 47 men, and with fewer mistakes. But he also noted that women were off sick more often than boys (which is still pretty much the case).

Stuchbury thought this was a clincher, but the secretary managed to head him off, pointing out that long term, women worked out a lot cheaper. There was, he argued, "a considerable future saving of expense… when it is borne in mind that women clerks would not attain higher pay than £85 against £300 earned by all other clerks."

In other words, the great thing about women was that you didn't have to promote them. The glass ceiling was in evidence (only then it was set at roughly ankle height) from the very start.

There was another good thing. Thanks to the marriage bar (which, extraordinarily, stayed in place until the 1960s), the supply of women was constantly replenished - as they married and left, new girls took their place.

But what of the women who didn't get married? Well they got promoted - but only a little. It was their job to look after the younger typists.

This was the plight of Hogarth. She wrote with some bitterness: "The girls show a zeal and zest which no boy thinks of emulating. But the trouble comes when they grow to be middle-aged women and are still kept at work only fit for beginners. They have become mere machines."

Hogarth left the bank in 1905 for a job as principal of Cheltenham College - possibly more fitting to a woman of her intelligence.

It would be a while before a woman had a crack at the interesting stuff at the Bank of England.

More than 100 years later, we've had four women on the monetary policy committee, though still no female governor.

This piece is based on an edited transcript of Lucy Kellaway's History of Office Life, produced by Russell Finch, of Somethin' Else, for Radio 4. Episode five, The Telephone and New Office Technology, is broadcast at 13:45 BST on 26 July