Breaking Bad: Why doesn't the UK have a crystal meth problem?

- Published

Methamphetamine has been used worldwide for decades, devastating the communities where it is found. So why is it relatively unknown in the UK?

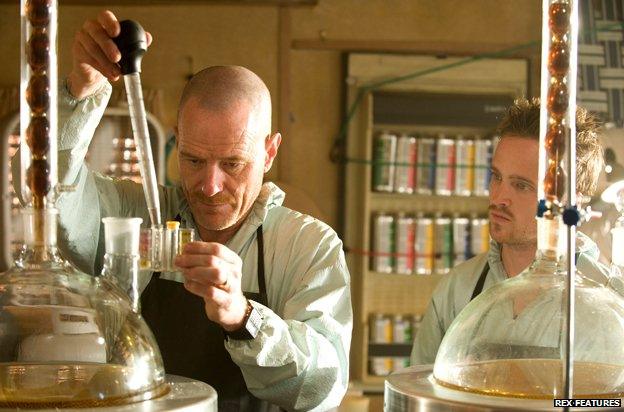

A little over five years since its protagonists first set out into the New Mexico desert to cook crystal meth in a battered recreation vehicle, the final episodes of TV drama Breaking Bad are about to be aired.

Telling the story of troubled chemistry teacher Walter White and his former student Jesse Pinkman's transformation into industrial-scale drug producers, it reflects a well-documented US problem.

According to the UN, methamphetamine - a term which includes the drug as a powder and its stronger and more addictive crystal form, external - was used by one million people in the US in 2011, down from 1.8 million in 2006.

Crystal meth ("ice"), also known as ice, tina or glass

The US is not alone in its experiences. In the Czech Republic, where it is known as Pervitin, it's a more serious problem than heroin, while in Greece a cheap and dangerous variant called sisa, external reportedly sells for two euros a hit. In New Zealand and Australia the UN estimates that it is used by about 1% of the population.

In the UK it's a different story - watching a Breaking Bad box set while slumped on the sofa is the closest most people are likely to get to the drug it features.

New figures from the Home Office estimate that in the past year about 17,000 people aged 16-59 in England and Wales took methamphetamine - fewer than for any other drug recorded. About 27,000 people had used heroin, 47,000 crack cocaine, 120,000 ketamine and two million cannabis.

"The prevalence has been pretty much confined to the male gay scene and even within that what you might call the heavy-end party scene of injecting crystal meth and promiscuous sexual activity," says Harry Shapiro of the charity Drugscope.

In the UK the drug is often used at sex parties and combined with others like Viagra and GBL, external, says Dr Owen Bowden-Jones, consultant psychiatrist at the Club Drug Clinic in central London.

Most of its 300 or so referrals for using crystal meth are from London, but some are starting to come from other cities like Manchester. A small number are from the straight clubbing community, but they remain the exception, says Bowden-Jones.

"On the West Coast of America it's a drug of deprivation, in London it seems to be a drug of affluent gay men and in Eastern Europe it's associated with prostitution."

One of the reasons for its unpopularity may be that British drug users have plenty of other stimulants available to them.

"The UK is a relatively small drug market overall and it's a market that has been well served," says Shapiro.

Australian police display a haul of crystal meth worth £342m

That other drugs are finding a market is borne out by the Home Office figures, which suggest that in the past year 174,000 people used mephedrone, 211,000 used amphetamines, 415,000 ecstasy and 627,000 cocaine powder.

The UN World Drug Report warned in June that the UK has the largest market for "legal highs" in the European Union. A total of 670,000 Britons aged 15-24 had used them at least once, it said.

One of the report's authors, Thomas Pietschmann, suggests that crystal meth has simply never been in fashion in the UK. "You had pop stars taking cocaine, you didn't have pop stars taking methamphetamine."

Another barrier may be the lack of wide-open spaces in which to manufacture it, says Gary Sutton of the charity Release.

Highlighting the experience of the US and Australia, he says: "These are huge countries and it seems to me that some of the meth labs are situated in the middle of somebody's field which is half the size of Kent."

But while it may be difficult to imagine a mobile meth lab - smoke billowing from a tinfoil chimney - failing to attract the attention of hikers and Sunday drivers in rural England, this is not actually a barrier to production, says Pietschmann.

"You can have large production facilities, but you can also have kitchen facilities to do it," he says.

In fact, some methamphetamine labs hidden in houses and industrial units have been found in the UK.

Instead, Pietschmann points to the relative difficulty of getting hold of the chemicals and expertise needed to make methamphetamine, compared with somewhere like the Czech Republic.

The drug has long been a problem there because production continued after the end of WWII - when it was given to troops to keep them alert - and the necessary chemicals were made there during the communist era, says Pietschmann.

The fall of communism was also a factor, says Shapiro. "There was a large chemical pharmaceutical industry out there that found itself with not much to do, so it had an infrastructure of drug manufacture."

It is differences like this that can explain why a drug is present in one country but not another, he says.

"Usually there's a reason, country by country, why some drug trends develop and others don't. There's an automatic assumption that whatever happens in America's going to happen in the UK, but that doesn't happen."

And then there's the cost. According to Drugscope a gram of crystal meth can cost up to £260 in the UK, compared with £46 per gram of cocaine, £13 for a gram of amphetamine, £16 per 0.25g rock of crack and £11 for 0.2g of heroin.

For many drug users that's enough to put them off immediately, says Sutton.

There is another factor that may be relevant to the UK as a late adopter, says Shapiro - its "fearsome reputation".

Known for its fast and long-lasting effects, methamphetamine delivers a euphoric high, but deeply unpleasant side effects. Smoked, snorted, swallowed, or injected, it can keep users awake for days.

2007 US campaign contrasted "before" and "after" pictures of addicts

There's a serious risk of cardiovascular problems, malnourishment through poor diet and, if injecting, blood-borne diseases. The problems of meth mouth, external - the tooth decay and loss associated with the drug - and "before and after" galleries, external of users would put off many.

But it remains possible that the drug's use could spread.

Seizures across Europe increased from 30kg in 2000 to 1,582kg in 2011 with many countries, including the UK, seeing an increase, says Pietschmann.

"What we have seen many times is that the gay community has been a sort of early warning," says Bowden-Jones.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external