The decline of privacy in open-plan offices

- Published

Millions of people have to work in open-plan offices where everything they do is visible to everybody else. Why, asks Lucy Kellaway.

The BBC newsroom must be one of the most scrutinised offices in the country. It's all open-plan, the desks are in lines, and there's a sea of people gawping at computer screens.

It's a bit like my own office. Only there's a difference. In mine, which is also open-plan, if I'm at my desk bidding for something on eBay, there's only the risk of my boss sneaking up behind me.

At the BBC, the risk is that you might be seen by 10 million people tuning into the news. So there's a ban on fluorescent jackets and people are only allowed to walk a certain route to the loo.

Looking at them you have to wonder - does it make sense for us all to work cooped up like this?

In Britain most offices in the early 19th Century were in damp basements and draughty attics, where clerks got backache.

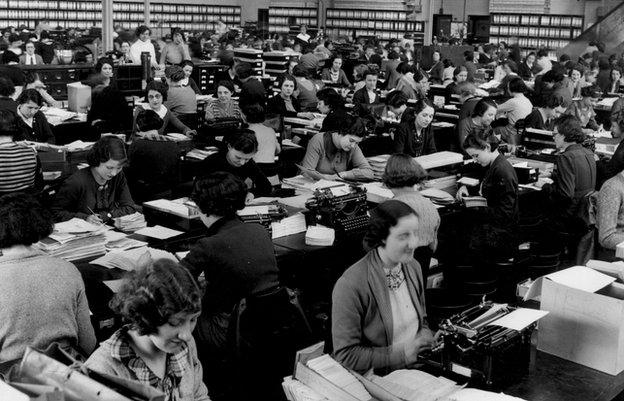

But by the end of that century gigantic purpose-built offices were starting to appear, which were about something new - power.

From the outside, the sheer scale stood for the might of the company, but on the inside it was all about power too. Those who had power got a private office, and those who didn't were out on the open-plan floor.

The first modern office was the Larkin Administration Building, which opened in 1906 in New York. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, it was based on an open-plan factory, with a giant atrium and very few walls.

An open-plan newsroom is a risky place to do your eBaying

"He was interested in creating big cathedral spaces for aesthetic reasons," says Jeremy Myerson, professor of design at the Royal College of Art.

"But actually it was very useful for managers because no walls meant they could supervise workers in this open space and keep an eye on them. It was all about control."

Conversation was forbidden on the office floor and motivational slogans were carved into the walls.

"Honest labor needs no master," read one, which I suppose was an early version of modern homilies like, "There's no I in teamwork".

But such exhortations were no more effective then than they are now - at least, they didn't stop Larkin Soap Company from going bust in the 1940s.

Even for those within the private offices, there were ways of enforcing the hierarchy.

Around the edge, where the windows were, sat the managers. The bigger the manager, the better the view.

"In a typical corporation the head gets a corner office with the nicest view. The offices of his subordinates branch out from this corner in descending order of rank. Closeness to power is evidence of status," wrote the American social critic Vance Packard in 1959.

"Desks too are typically categorized by rank. Mahogany outranks walnut. Walnut outranks oak," he added.

The signs of power weren't all about size. Truly grand managers had offices that looked domestic - to distance them from any sign of actual work.

And the point of the office wasn't just to impress visitors, it was to put them at a slight disadvantage.

A manager explained his office layout to efficiency expert Lee Galloway in 1913:

"[When] a salesman calls I motion him to a seat opposite the window. The light, by striking him full in the face, enables me to read many subtle meanings in his eyes and facial expression.

"On the other hand, if I am trying to sell a visitor something, the chair near the radiator is selected. The visitor is permitted to look into my face, which is in the full light, and hence I add to my other powers of persuasion the influence of my facial expression."

The Hollywood film mogul Harry Cohn insisted on having his huge semi-circular desk on a raised platform a full 9m from the door. "By the time they walk to my desk," he said, "they're beaten."

I've sometimes found myself on the wrong end of this type of trick. I remember in the 1980s going to visit Lord Weinstock, the head of General Electric Company, to find him sitting in a pool of light over his desk, while I sat in the dark.

The opposite approach, of course, was to take away the office altogether and make the boss work with everyone else.

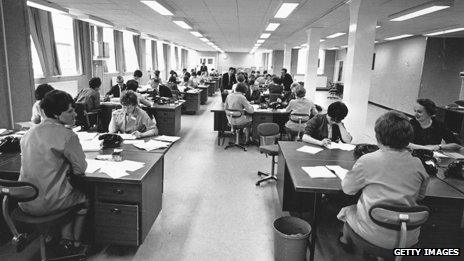

It was the Germans who were first on to this idea in the 1960s as part of a general reaction to hierarchy. The new movement was called Burolandschaft - meaning office landscaping.

Out went regimented layouts and enforced silence, and in came a load of pot plants and the idea that everyone could talk to everyone. But hierarchy wasn't as easily dispensed with as all that.

The architect Francis Duffy described visiting an important person in such an office.

"That he is of some importance is made clear by the fact that he enjoys more space and better equipment than his staff," he said.

"But still he takes his place on the open floor, as does the managing director. In this office, no one is shouting, even the telephones have lost their strident ring."

Meanwhile in the US they were nowhere near ready to strip the boss of his corner office, but were starting to realise that the factory-style offices came at a price.

In the 1960s Herman Miller, manufacturers of office furniture, hired a fine arts professor called Robert Propst to go round with a clipboard asking questions of thousands of office workers.

They were things like - "what percentage of your working day is spent in these positions - sitting/standing/walking/perching/supine/sleeping/other?" and, most delightfully - "can you take a nap in your office without embarrassment?"

He wasn't impressed by what he found.

"We are trapped in a game of continuous idiot salutations," came one answer.

"We cannot avoid exposure, we see everybody going by. We may see the same person go by 30 times. Now do you invest in a recognition act every time someone goes by? You are distracted and irritated by this exposure overload."

His solution was the action office, a system of furniture that could be individually customised. One of its elements was something that would affect American workers for the next three decades - dividers.

US companies went into raptures - partly because dividers were tax deductible after seven years instead of more than 30 for walls - and thus, the cubicle was born. Herman Miller's stock price increased 40-fold.

"It combined the alienation of the private office with the tedium of listening to people at a bus stop," adds Myerson.

And so now we are back with open-plan. No one in the US builds cubicles any more, and in the UK they never really did. It's back to rows of desks, where if someone wants privacy then they put on their headphones.

You may not even have your own desk anymore - you may have to share. Hot-desking is a nasty arrangement with a nasty name.

Of course, the real reason companies love open-plan is that it's cheaper.

But it's also because we remain wedded to the idea that it is essential to be able to see each other. When walls exist, they are all made of glass, which means there is nowhere to hide.

If you want a private conversation at work, you're better off having it in a public place - the stairwell or coffee shop - than in the goldfish bowl in the office.

There's a certain comedy in the idea that in the first open-plan offices people were supposed to talk as little as possible. Now we've gone to the opposite extreme and we're meant to talk to each other as much as possible.

But perhaps we should be wary of designing a perfect office space.

As C Northcote Parkinson pointed out in the 1950s: "A perfection of planned layout is achieved only by an institution on the point of collapse."

This piece is based on an edited transcript of Lucy Kellaway's History of Office Life, produced by Russell Finch, of Somethin' Else, for Radio 4. Episode nine, Whatever Happened to the Paperless Office?, is broadcast at 13:45 BST on 1 August