Exploring Los Angeles' forgotten stairways to the stars

- Published

From the air, the hills of Silver Lake, peppered with bungalows, must look like a leafy game of Snakes and Ladders. Roads insinuate their way up and around the mountain slopes and connecting them all from the lowest to the highest are dozens of vertiginous stone staircases. These are the historic Los Angeles Stairs, hidden and unknown to most of the city's residents and visitors.

I was on an early-morning hike between them with Charles Fleming, an LA Times editor who has spent years researching and mapping the stairways, originally as a form of convenient local exercise.

For him they are civic treasures that lead the curious through unfamiliar neighbourhoods and their architectural treasures: historic homes where famous actors lived, celebrated screenplays were written and, as we were to discover, the stairs themselves have earned their place in cinema history as the location for an Oscar-winning comedy.

LA hasn't always been a city of cars, it once had one of the most effective public transport systems in the United States. In the 1920s, as the city expanded, developers naturally wanted to build up into the hills. Few people could afford cars so the city planners built long stone staircases to connect the pedestrian residents of the lofty hillside homes to the tram network below.

We began our walk early one morning and I asked Charles why such an efficient and healthy public transport system disappeared. He said that in his opinion the story was told very well in the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit, where the oil, automobile and tyre companies conspired to replace the trolley network with freeways for buses and automobiles. The busy stretch of Silver Lake Boulevard we were walking along had once been a major tramway with another, Sunset Boulevard, crossing overhead.

We turned into a dusty alleyway. By the 1970s and 80s the area had become rundown - the staircases weren't maintained and became hidden spaces for criminal activity. Many were closed off and fell into disrepair.

On a fence, Charles pointed out some graffiti. "That's the first sign of trouble," he warned, explaining it was the tag symbol for a local gang. "The second is when you see a line struck through it by a rival gang, that means there is a turf war for control of the area."

Sure enough, the first stairway we came to had been locked, much to Charles's annoyance. The stairs are public byways, paid for and maintained by taxpayers' money and he believes they should be kept open.

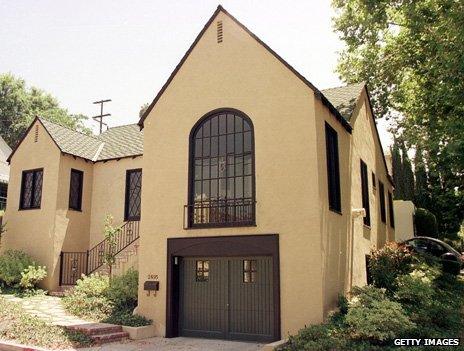

Walt Disney worked on early Mickey Mouse cartoons at his Silver Lake home

The film studios were the first to develop the area, building compact bungalows to house their actors and technicians. Both Chaplin and Disney lived here.

Movie carpenters would build sets during the week and homes at the weekend. Charles said this accounted for the local architectural hotchpotch that is often ridiculed. A Moorish castle next to a Spanish villa, next to a Tudor mansion - the carpenters were inspired by whatever they had been building on the studio backlots that week.

Our second staircase was thankfully unobstructed. Here, in 1932, Laurel and Hardy tried and failed to move a piano to the top in The Music Box. The film won an Academy Award. I'd seen it over and again as a child and remembered it fondly.

There were now buildings either side but it was still quite recognisable. For such a historic landmark it was still remarkably unkempt, its history simply marked by a defaced granite plaque inset into one of the lower steps.

Looking down from the top of The Music Box steps

This wasn't the only staircase to feature in the movies. In An Ache in Every Stake, filmed in 1941, two miles to the north-east, The Three Stooges tried to deliver a block of ice to a house at the top of 147 steps and each time they reached the summit the block had melted to an ice cube. "Unlike The Music Box stairs," Charles informed me, "the area around that staircase is pretty much unchanged."

We climbed another flight of steps that are a street in themselves with the houses on either side only accessible from the stairs. From the top we had a clear view of the Griffith Park Observatory and the Hollywood sign.

Charles has found more than 500 staircases across the city but only half are accessible. I asked about the longest: "That's Murphy's Ranch in Pacific Palisades," he said. "It is the only one that was originally private. It has 511 steps and was built by a group of Nazi sympathisers."

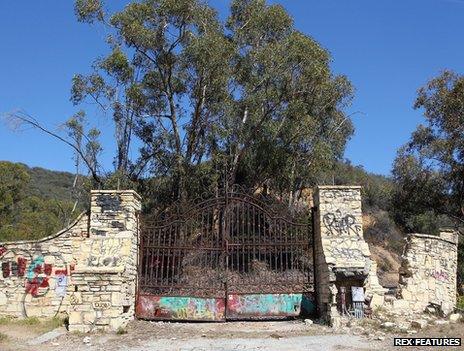

Murphy's Ranch as it is today

In the 1930s - according to his own paper, the LA Times - the owners of the ranch, Winona and Norman Stephens, fell under the spell of the mysterious Herr Schmidt, who claimed to have supernatural powers. He persuaded them to spend $4m to build a self-sustaining Nazi utopia where a small and committed band of followers would wait until Germany won the war and then emerge victorious to establish the Third Reich in America.

The compound was impressive with its own power station, water tanks and an irrigation system built into the terraced hillside to water the crops and trees that would sustain the Nazi faithful.

It naturally aroused the concern of the US authorities and was raided by federal agents in 1941, the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Schmidt was arrested as a spy and the land was eventually handed over to the people of Los Angeles as a public park.

The ruins of that compound are now covered in graffiti and I asked Charles if locals are concerned with the history of their city. "No", he said. "Most of them have a private experience of life - 'I ride in my car, I sit in my office, I live in my house'.

"They are isolated from the larger public space because they haven't been encouraged to be interested. When you give them permission to look, they are surprised by what has always been just around the corner from them."

I wondered how much the temporary nature and rapid turnover of the movie business had contributed to this throwaway attitude to the city's heritage.

"I think that has something to do with it," he said. "People weren't aware that they had a history to destroy. If there seemed a better way of doing something they would tear down what they had and build something new."

Covent Garden Market (here in 1925) and St Pancras Station (here in 1905) were both saved from demolition

I noted that London had suffered a similar disregard for many of its architectural landmarks after the war. Covent Garden Market and the gothic magnificence of St Pancras Station were earmarked for demolition and only saved by a small band of passionate protestors.

There is now a proposal to dredge up the fragments of the grand doric arch that greeted visitors to Euston Station from its watery grave on the bed of the River Lea in the East End of London.

But the mere fact Charles and I were taking this walk, like the many devotees of his book and tours signals hope for LA's hidden heritage.

Zeb (left) and Charles after their walk

Online blogs and organisations such as the LA Conservancy are encouraging locals and visitors to learn more about the history beneath their feet and, whilst for decades LA hasn't had a reputation as a walking city, great strides are being taken to restore an efficient public transport system to reconnect the sprawling city.

The route of the former Pacific Electric trolley service, closed in 1953, is being relaid with a pristine light railway that will once more take downtown dwellers all the way to the beach, leaving their cars at home.

Everything comes full circle, as indeed had we. We had been walking an hour but our chat made it feel a brisk 20 minutes. We were back where we started at the bottom of the hill, just like Laurel and Hardy's battered piano.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external: BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00 and you can listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external