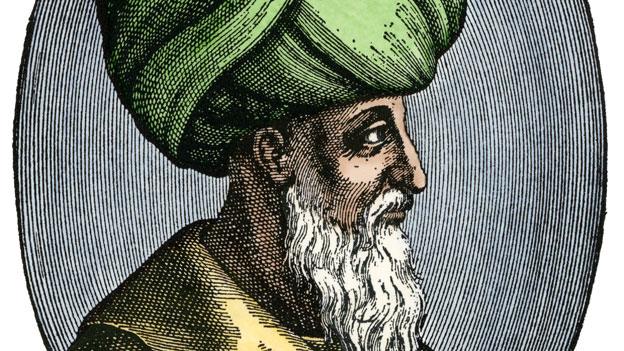

The search for Suleiman the Magnificent's heart

- Published

Later this month a team of Hungarian researchers will publish a report on the whereabouts of the heart of one of Ottoman Turkey's most famous sultans. But why has this become such an important historical riddle to solve?

The French statesman Cardinal Richelieu described it as "the battle that saved civilisation" - the siege of the Hungarian castle of Sziget, 447 years ago, almost to the day.

The Muslim Turks finally took the town in September 1566, but sustained such losses, including the death of their leader, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, that they did not threaten Vienna again for 120 years.

Now researchers are digging in the soil - and the archives - for the good sultan's heart.

"When Hungarians walk through the grounds of the castle in Szigetvar they imagine they are walking through a Hungarian castle. But of course, that is not true," says Norbert Pap, Professor of Geography at the University of Pecs, as we stroll along the beautifully restored brick ramparts.

He smiles. "This is in fact the Turkish castle. The Hungarian one was destroyed in the siege of 1566."

Like the rolling hills of the surrounding Zselic region, each fold of history concerning that siege and what followed, seems to conceal another. And each substitutes another version of events.

On the surface the legend is easy to follow.

Suleiman the Magnificent arrived here with up to 100,000 crack Ottoman troops in early August 1566.

The castle was on his route to Vienna, which he confidently expected to capture, and thus pave the way for the addition of great chunks of Western Europe to his dominions.

The air trembled to the beat of the big war drums - made, as they still are today, in the handsome city of Edirne. I once bought one there for my son.

But Miklos Zrinyi, the commander of the castle, and his garrison of only 2,300 men put up such a brave fight that the Turks were stopped in their tracks.

Zrinyi died in the final sortie from the burning castle.

Suleiman died in his tent - some sources say from surprise at his Pyrrhic victory. He was 72, after all, and had been fighting the Hungarians for 40 years.

His body was taken back to Constantinople, but his heart was buried here, in a tomb which subsequently became a Catholic church, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, or so reads the inscription on the Turbeki church, just east of the town.

But that's just a fairy story, Prof Pap explains. The plaque was put there in 1916 by the local priest, for political reasons.

At that time Hungary - or the Austro-Hungarian Empire - was an ally of Ottoman Turkey, two ancient empires stumbling to their ruin in the mud and blood of World War I, and they needed symbols of undying friendship.

Now Prof Pap has been tasked with finding the true burial place of Suleiman's heart, also for political reasons.

Relations between Hungary and Turkey are enjoying a big revival.

The two prime ministers get on well. The number of Turkish tourists visiting Hungary has leapt by 45% in the last year.

But there are only 500 beds in this sleepy town, where tens of thousands once slept in tents, listening to the nightingales, preparing for battle.

At stake are a five-star hotel or two, and the further restoration of the castle and a host of Ottoman-era monuments. But everything hinges on finding the resting place of Suleiman's magnificent heart.

There are several maps. One from 1689 even marks the supposed burial place. Others in the war archive in Vienna were prepared for the Habsburg troops who retook the town in the 1680s.

Suleiman had already laid siege to Vienna in 1529

There is more information in the archives of the Vatican, in Venice, in Budapest, and in Istanbul.

Prof Pap and his team of researchers have been combing through each. Their results will be made public on 20 September.

Permission has now been granted for a new dig - at the one site Prof Pap does not take me to.

"This is not just about Suleiman's heart, but about reconstructing each layer of the history and geography of the past 400 years - we have already discovered a lot," he teases.

The maps are misleading. When the Habsburgs conquered the castle in 1689, Serbian irregulars drove out the remaining Muslims.

German Catholics were resettled here in the 18th Century.

Even the landscape has changed. A mini ice age coincided with the Ottoman occupation, Prof Pap explains.

What is now the little Almasi brook was then a raging torrent. Sziget means "island" in Hungarian, rising out of the marshland of the river's inundations.

Nearby, in the Hungarian-Turkish friendship park, is the place where Suleiman's army encamped.

There is a tomb for Suleiman here too, with fresh flowers - "purely symbolic," says Prof Pap. And a Bronze Age burial mound, which generations of locals mistakenly called "the Turkish graveyard".

The mayor, Janos Kolovics, proudly traces his family roots to Bosnia, in Turkish times. He opens his laptop to show an artist's impression of a new, concrete visitor's centre, to be built beside the town's mosque.

It's a Hungarian design, and the Turks don't like it at all, he says, wistfully.

With Prof Pap, I kneel in the mosque to examine dervish graffiti in the plaster - calligraphic images of the face of God, frowned on by mainstream Islam.

Somewhere beneath us, in the dry Hungarian earth, Suleiman's heart beats faster.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external