The bizarre world of 1970s hyper-local TV

- Published

An episode of BBC Horizon captures images behind-the-scenes at the Swindon and Greenwich local stations in the 1970s.

Local TV may be coming to a screen near you soon - but not for the first time, as the UK already has a rich history of local television, writes social historian Joe Moran. But did viewers really want to watch pub darts and barber shop singers?

Last week, the Local TV Network launched an awareness campaign, beginning with a session at the Edinburgh International Television Festival on Local TV: The Next Big Thing?, ahead of the first stations going live this autumn.

What is less well known is that back in the early 1970s, residents of south-east London, Sheffield and Milton Keynes were already enjoying a diet of hyper-local entertainment.

Local television began as an offshoot of the cable TV network, which had thrived in areas where reception was poor or the analogue transmitters did not yet reach.

The first of these stations to open, in July 1972, was Greenwich Cablevision. It should really have been called Plumstead Cablevision because it operated from a shop on Plumstead High Street. It benefited from the fact that Plumstead had a dreadful terrestrial TV picture from the Crystal Palace transmitter which, on its way east, bumped into the immovable object of Shooters Hill, one of the highest points in London.

Greenwich Cablevision solved this problem by picking up its signal from a mast on top of one of the borough's new high-rise blocks and piping it to thousands of homes.

It had a Saturday night variety show called Greenwich Meantime which offered early career breaks for Jim Davidson and the comedy duo Hale and Pace, and a weekly Special Report, which, among other things went behind the scenes of the "Entertainments Department of Greenwich Council".

Sheffield Cablevision, which broadcast dominoes and darts from Sheffield pubs in an imitation of Yorkshire Television's Indoor League, and Hullabaloo, an anarchic Saturday morning children's programme inspired by ATV's Tiswas, was also helped by bad terrestrial reception. Sheffield, which nestles in a valley, has more than two million trees - a problem for television signals in the summer when they are in leaf.

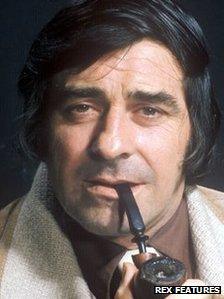

Fred Trueman presented Yorkshire Television's Indoor League

The fact that tenants in Sheffield's 20,000 council homes were forbidden to erect roof aerials also helped the new cable channel. But it was on air for only a couple of hours a day. At other times it showed a channel ident with Radio Hallam playing in the background - and, in an era when almost half of homes now had colour television, it broadcast only in black and white.

Since the government would not allow them to run commercials like ITV, these local cable channels were perennially poverty-stricken and had closed down by 1976 - with the exception of Swindon Viewpoint, where volunteers managed to carry on after its former proprietor EMI generously bequeathed them the station's equipment for £1. Milton Keynes Channel 40, which went on air in December of that year, had more luck because it was generously funded by the Milton Keynes Development Corporation, which hoped it would foster a sense of community in a new town full of displaced families.

Channel 40 was run by seven full-time staff and a small cadre of volunteers - many of them techno-literate young men, with a seasonal rush of students and schoolchildren in the summer months - and was piped in to all new houses in Milton Keynes for free, four hours per week. Competing against Crossroads and Nationwide in the almost primetime hours between 18.00 and 19.30, it pulled in 16% of the audience. But it ceased in 1979 when its funding came to an end.

In 1989, while filming a Channel 4 series called The Television Village, Granada Television helped the residents of Waddington in Lancashire's Ribble Valley set up a local station, Waddington Village Television. The Independent Broadcasting Authority lent them a small TV mast which was erected next to a local farmer's pig slurry tip.

Milton Keynes got its own station in a bid to foster community spirit

The village channel broadcast between 19.00 and 20.00 each evening from the church hall, its badminton lines still visible on screen. The programmes included cub meetings, music from the local barber shop singers and the vicar giving his thought for the day. Barring a technical glitch when sheep nibbled through the wires leading from the transmitter, the village station gained 95% of the available audience, beating EastEnders in the ratings.

Residents of neighbouring villages even adjusted their aerials to pick up the evening hour of WVTV.

The two dozen local stations formed after the 1996 Broadcasting Act, which allowed new channels to take out restricted service licences to broadcast on spare analogue frequencies, were less successful.

The Isle of Wight's TV-12 channel, which was based in a converted caretaker's bungalow in the grounds of a Newport school, filmed local bands playing in pubs and a productions by the amateur dramatic society, The Ferret Theatre Company. But it was replaced by Solent TV which, even after it diluted its local content with cheap imports such as Futbol Mundial and old black-and-white films, went out of business.

Lanarkshire TV, meanwhile, had a talent show called Talented Lanarkshire, a quiz night from Lanark Grammar School and a local constable appealing for witnesses in a small-scale version of Crimewatch.

Quiz nights or the Christmas play?

It was replaced by Thistle Television, which broadcast to a wider catchment area and interspersed this local material with Sky News and the QVC shopping channel. Like almost all the more recent local channels, it failed to attract enough investors or advertisers and stopped broadcasting in 2005.

It is an interesting time for the relaunch of local television because in the digital era, mainstream television has lost its connection with place - witness the demise of the ITV regions, which were defined by the reach of the analogue transmitters.

The lesson from history seems to be that when local TV is very local, such as in the case of Milton Keynes Channel 40 or Waddington Village Television, it can be surprisingly addictive, and viewers may prefer watching programmes about their own community to glossier alternatives, because there is novelty and interest in seeing their own High Street or the local school's Christmas play on screen.

But when small stations with low advertising revenue attempt merely to mimic mainstream programmes, which can draw on lavish central budgets and high production values, viewers usually prefer to watch the main channels.

Joe Moran is the author of Armchair Nation: An Intimate History of Britain in Front of the TV.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external