Tesco: How one supermarket came to dominate

- Published

Tesco occupies a unique place in British retail, visited by millions but controversial to many. It all started with a barrow selling fish paste.

There's a famous stat - that at its peak one pound in every seven, external spent in the UK went into a Tesco till.*

It's the UK's biggest retailer by sales and also the nation's biggest private employer, with more than 330,000 staff working in 3,146 stores. Pre-tax profits are in the billions and its achievements and failures make national, often international, news.

It's the world's third largest supermarket group, with stores in 12 countries. More than 27 million people outside the UK have a Tesco Clubcard.

It's part of the fabric of daily life. Nearly everyone has an opinion on it, often vehement.

It all started in 1919 with Jack Cohen. The 21-year-old left the Royal Flying Corps at the end of World War I and used his demob money to buy surplus food from the Army and sell it from a barrow in Hackney. His first stock was fish paste and golden syrup.

By 1924 he had started selling his first own-brand product, tea. Looking for a name he took the first three letters of his supplier, TE Stockwell, and combined them with the first two letters of his own. Tesco was born and the first shop was opened in 1929 in north London.

Cohen believed in the business model "stack 'em high, sell 'em low". It earned him the nickname "slasher Jack".

"Cohen built his business when there was still a lot of austerity around," says Phil Lyon, a retail historian at Queen Margaret University Edinburgh. "To drive business development of that kind at that time was quite remarkable. He totally understood what worked for the mass market."

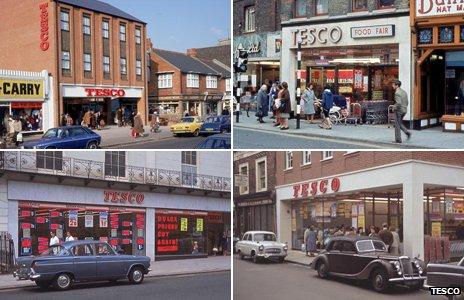

The first Tesco store was opened in Edgware, north London, in 1929 by Sir John "Jack" Cohen, selling dry goods and Tesco-branded tea.

Staff deliver goods to the first "self-service" Tesco in St Albans, Hertfordshire in 1948. Cohen adopted the model after a research visit to the US.

It introduced the pioneering Green Shield reward scheme in the 1960s. The scheme was phased out in 1977.

Cohen continued to expand the business, adding superstores and ever more branches to his portfolio.

As well as petrol stations, superstores and High Street shops in the UK, Tesco expanded abroad - with mixed results.

In the recession at the start of the 1990s Tesco quickly realised shoppers wanted their money to go further.

The company launched its Value range in 1993. It went on to become the second biggest grocery brand in the UK at its peak and the brand alone generated an estimated annual turnover of more than £1bn. By 1996 Tesco's sales in the UK had jumped ahead of Sainsbury's.

The size of the company's orders allowed them to negotiate bargains with even the biggest manufacturers.

"The sheer size of all the main supermarkets gave them immense power," says David Gray, analyst at Planet Retail. "Tesco was very aggressive, getting the best deals."

How "Slasher" Jack Cohen built his business from barrow to behemoth

As this power grew the relationship between all the big supermarkets and their suppliers came under scrutiny. In 2000 the Competition Commission carried out a major inquiry, external into the issue which lead to the creation of a Code of Practice. It's an issue that rumbles on, with dairy farmers protesting last year about the low price some supermarkets pay for milk.

Tesco says it negotiates the best prices on behalf of customers but that it is also fair and that suppliers stay with the company. It says it pays one of the highest prices for milk out of all the main supermarkets.

But what really took Tesco to the top was watching customer behaviour. It was the first British supermarket to do so and it was a game-changing move.

The introduction of the Tesco Clubcard is the single most significant factor in the success of the company, says Sir Terry Leahy, the supermarket's chief executive from 1997 to 2011.

"I knew the whole industry's structure would never be the same again," he says.

The idea of a loyalty scheme was not new. The savvy Cohen had been an early adopter of Green Shield Stamps in 1963 and successfully exploited the incentive scheme to his advantage. But the Clubcard was a loyalty scheme for the age of computerised research.

Tesco collected raw data on what people were buying and turned it into profitable information. It was also able to offer personalised discounts and rewards. Rolled out nationally in 1995, the card was an instant success. One year later Tesco became the UK's top supermarket.

The scheme fundamentally changed the way all supermarkets did business and typifies Tesco's success, say business analysts.

"It became such a success story because it was aggressive at adapting to consumer trends, diversifying and innovating," says Gray. "It took a hell of a lot of risks in the 1990s but they paid off."

And diversify it did. Tesco is now a bank, it offers insurance, credit cards and loans. You can buy a flat-screen TV, a mobile phone and clothes alongside bread, milk and butter. It runs education programmes for staff and keep fit classes.

Even its critics have some grudging regard for the company.

"You have to respect the clinical efficiency with which Tesco carried out its business plan," says Andrew Simms, author of Tescopoly: How One Shop Came Out on Top and Why It Matters. "With the Clubcard it totally understood information is power."

Tesco went on to cement its dominance by expanding massively - the source of much of the controversy. Again it had its roots in Cohen's ideas. He always believed in owning the shops he did business from. Between 1955 and 1960 alone he bought more than 500 new shops.

But it was during the recession of the 1990s that it really grew. Big sites were acquired for a new generation of out-of-town superstores. Again it spotted the market before its competitors. The same happened when it headed back into towns and cities and started opening smaller convenience stores - the Tesco Metro - in 1994.

Its property portfolio was huge and included land it didn't develop. Critics noted that if Tesco owned it no other supermarket could build on it, leaving them struggling.

"They didn't catch up then and they haven't caught up to this day," says Lord MacLaurin, chairman of Tesco from 1985 to 1997.

But while the new developments were initially seen as progress, they came to divide opinion. Supermarkets as a whole have been criticised for creating "clone towns". National organisations like the Association of Convenience Stores (ACS) have expressed concern about the impact their "aggressive expansion" has had on small businesses.

In 2006 the Office of Fair Trading referred the market to the Competition Commission for a second time. It concluded that in many respects UK grocery retailers were "delivering a good deal for consumers, external" but action was "needed to improve competition in local markets".

"All supermarkets came under fire, it was a problem for the whole industry," says Gray. "As they got bigger and more powerful they were always more likely to come under attack."

Because of its huge expansion Tesco has often been singled out for more vehement criticism. The National Consumer Council has called it the Marmite of British business, appearing both among the most trusted and the most distrusted companies in consumer surveys.

"It's because of its sheer size and clout," says Simms. "It's incredibly hard for smaller operators to compete against."

Wrangles over planning permission for developments often find Tesco in the news.

Smaller disputes are pitched as David and Goliath battles. Just last week campaigners in Sherborne, Dorset, claimed victory when the supermarket decided not to open a store in the town.

"Joy for Sherborne as people power beats off plans for Tesco superstore" was the headline in the Times. "Brilliant news for the people of Sherborne and their fantastic town. They've beaten Tesco!" tweeted retail expert Mary Portas.

But Tesco said planning issues and not protest influenced the decision.

In 2011 a raid on a squat occupied by opponents of a newly opened Tesco store in Bristol left eight police officers and several protesters injured. It resulted in rioting during which the shop was attacked.

On the flip side there is a group campaigning for new Tesco stores. Earlier this year in Felixstowe people staged a rally with placards that read: "Yes to Tesco". They said they didn't want to lose the chance of the supermarket opening a superstore in the area as it would give local people "real choice".

But despite its dominance, times have got tougher for Tesco. This year its profits fell for the first time in 20 years. It was said to have taken its "eye off the ball" in the lucrative UK market and focused on foreign markets too much.

What does it mean for the company? Based on history, the chain will probably adapt and change, say business analysts.

Maybe it should ask itself what Jack Cohen would do.

* Tesco doesn't use this figure as the ratio varies from year to year. For 2013, based on ONS retail sales figures and Tesco UK sales of £43.6bn it is more like one in eight.

Robert Peston Goes Shopping is on BBC Two at 21:00 BST on Monday 9 September or catch up with iPlayer.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external