Imagine a world without shops or factories

- Published

I have come to think that our world is being turned upside down. We probably do not grasp the huge implications because, perhaps, we are still imprisoned by our past.

We are all of us, almost everywhere, swept up in a maelstrom of change which overturns many of the assumptions we have lived with for the past 100 years.

That 100 years is important, because it is the span of the era of mass production ushered in just after 1910 by Henry Ford in Detroit. It is an era which I fancy may now be coming to a close, or at least becoming severely limited. The first industrial era is being replaced by something else.

Henry Ford memorably said about his Model T car: "Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants, so long as it is black". But why particularly black? It is not a matter of style or taste, it is just that black paint dries fastest, so the cars came off the production line faster. A hugely practical man, Henry Ford.

But let's begin close to the beginning, to the first signs that the 21st Century may be very different from what we got used to in the 20th.

In the spring of 2004, I had a revelatory encounter with the impact of China on the world. I was standing on a long quayside in the harbour of Qingdao on the Yellow Sea.

Ahead of me on my left, were mountains of iron ore just shipped in from abroad, lying rusting in the sun. And then, swivelling my gaze across this extraordinary panorama of emergent industrial might, I saw thousands of containers on the wharf side, piled up to the height of city blocks, full of manufactured exports awaiting shipping to the world.

The new Chinese industrial revolution was out there in front of me. In one glance, I saw the grip of China on the global economy - a huge rise in the price of vital raw materials such as iron and food, and at the same time, a great fall in the price of manufactured goods the world was rushing to buy from China.

It was an emblem of our developed world challenged to its core by a mighty upstart, then a series of Asian upstarts. The world was beginning to be turned upside down.

Here was the thesis of British economist Jim O'Neill asserting itself - the ascent to the world's economic top table of the "Brics" nations, Brazil, India, Russia and China.

O'Neill was the chief economist of the investment bank Goldman Sachs 12 years ago when he got an international reputation for some eye-catching predictions.

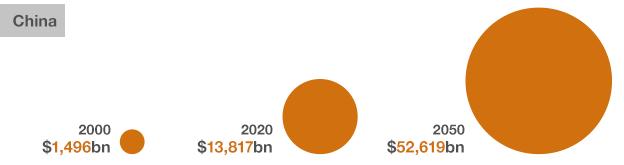

He argued that if the developing nations went on growing as they were, then China would in just a few decades have the largest economy in the world.

Bigger even than that of the previous Big Boy, the US.

And to appreciate the speed and scale of China's transformation, we need only look at the UK - which was slightly bigger than China back in 2000.

And as China would still be much poorer per head than the UK or the US, the new number one would go on pulling away. New emerging economies coming out as global top dogs excited the investment world.

But the people in charge of most companies seemed to feel (with one or two notable exceptions) that it would not happen on their watch, and so it did not really matter. But it did and it will, just as I saw in Qingdao.

Then I had another encounter on the way home from China to Britain via California. In Palo Alto, Silicon Valley, I went to revisit Joe Kraus. He had been one of five Stanford graduates who had gone straight out from the university to found a search engine called Excite in the middle of the 1990s.

The company sold its shares to the public - at 26, Joe Kraus had just become a multi-millionaire when I first met him in 1996. Excite grew exponentially and merged to become Excite@Home. By 1999 it was a $6.7bn enterprise with hundreds of employees and what seemed to be an almost infinite future.

And yet, a year later the dotcom bubble burst, and before the end of 2000, Excite@Home was effectively defunct. At the same time, a few miles away, another little Stanford University graduate start-up - a rival search engine called Google - was turning itself into the largest media company in the world.

Reviewing this jolting experience a year or so later, Joe Kraus had by then acquired a significant insight into why Excite had failed and Google had triumphed. He talked about how Excite had been a 20th Century company seeking all its revenue from the top 10 companies in America, as media businesses had been doing for decades. But - and this is the upside-down revolution - Google structured its business around attracting the top million, or ten million, advertisers in the US.

And then Joe Kraus told me something that I regard as one of the keys to understanding how different life is now compared to the world in which I have spent most of my life. It's one of the most important statements we have ever broadcast on my Radio 4 programme In Business.

He said: "The 20th Century was about dozens of markets of millions of consumers. The 21st Century is about millions of markets of dozens of consumers."

And that single phrase, "millions of markets of dozens of consumers", really does turn the conventional, mass production, 20th Century business world, upside down. The really revolutionary thing is what is happening to the notion of the "consumer", a term which seems first to have appeared in print in the Sears Roebuck catalogue at the very end of the 1800s, but which rose to prominence in the second half of our 20th Century.

In many societies, consumers are now beginning to challenge their passive role as users of stuff provided by others. They are becoming much more like creators than they have ever been allowed to before.

I also had a seminal encounter with its rival Google in 2002. This was four years after the company was founded, two years before its spectacular launch on the stock market. I went to the old, homey, Googleplex, not the vast campus that the company now inhabits. The corridors were full of bicycles. There was a grand piano in reception for lunchtime recreation and lava lamps everywhere.

But above the reception desk was something I had not seen before. On a big screen they projected live (but with sex-based terms omitted) some of the global searches being done by users from all over the world, then and there. My guide David Krane and I read them out one by one in to my microphone, and then I stopped, in absolute awe. I realised that we were looking at the mind of the world.

Here was a semi-structured connectivity of millions of people now, and billions still to come. The new mind of the world. The new nervous system. This was indeed our old world turned upside down.

That world that we were all shaped profoundly by owed far too much to Henry Ford.

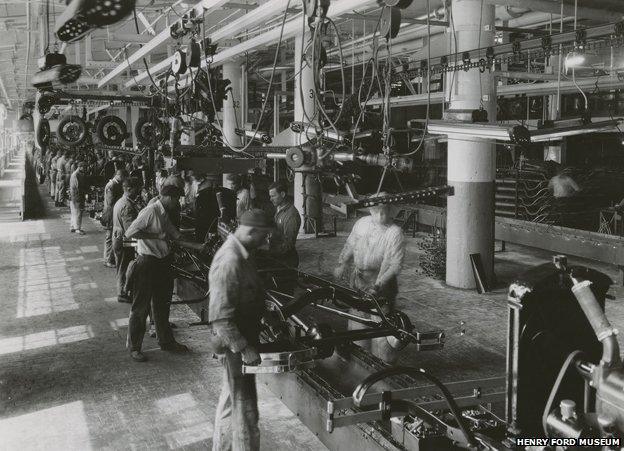

Just over 100 years ago in Detroit, Ford had borrowed some potent ideas from other people and created an even more potent one. He took the concept of interchangeable parts from the US weapons industry. He took the moving line from the Chicago slaughterhouses. From them he produced the factory-scale assembly line. An impossibly practical man, he did it in pursuit of efficiency, of reducing costs, of making things cheaply - all of them black (at least to start with).

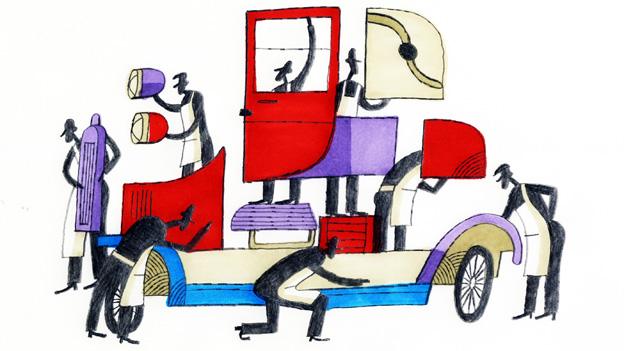

But he reduced work on his new production lines to a sort of lowest common denominator activity. This was because nearly all the trained and experienced engineers in Detroit at the time were already employed making railway wagons. Ford took his new unskilled workers with little understanding of English straight off the immigrant boats. He broke down the work they were required to do to make a Model T Ford into the simplest repeatable activities, driven by the moving production line.

The relentless nature of the work meant he had to pay the workers exceptionally well. In 1914 he more than doubled autoworkers' previous pay to $5 a day - enough for them to be able to afford a Model T. And he knocked an hour off the working day, too. Both things had a huge big impact on the productivity of the Ford plant.

Ford workers disliked the new assembly line methods so much that by late 1913, labour turnover was very high. In order to expand the workforce by 100 men, the company had to hire 953.

So the company increased pay to $5 for an eight-hour day from the previous rate of $2.34 for a nine-hour day. Workers flocked to sign up in January 1914.

The work was no easier, the pace no less relentless. But the pay was so good that workers were willing. The new wage went only to people deemed "qualified" after an investigation into their private lives.

The company set up a sociological department to monitor its employees' personal and work lives. Advisers conducted home visits, checked bank deposits and monitored children's school attendance.

As many employees were recent immigrants, the company also ran English language lessons. Advisors also provided hygiene instruction, along with financial and legal advice.

... but the lure of the money was so strong that most workers put up with such paternalistic policies, however reluctantly.

This bargain between Ford and his workers - submission to discipline in return for high wages - would turn out to be as important as the Model T itself.

What is so extraordinary is how this Fordist model of mass production and this mechanised quest for ever greater efficiency so quickly came to dominate not just car manufacturing but production in general, in nearly every industry.

The production-line big corporation became the absolute model for business everywhere in the industrialised world and the concept of work for millions of people. It brought huge prosperity and material goods to people who had never been able to have them before. It created the suburbs where people who made the cars and bought them could live.

Then, after 80 years of Fordist Western domination, the rich world manufacturing machine began to move away to other, far flung locations. But here too, in the mighty Chinese industrial revolution and when services were outsourced en masse to India, mass production prevailed.

During the last decade of the 20th Century and into the 21st, I felt that the only way for businesses to be sure of survival in the developed world, in the US and in Europe, was to abandon competing with the world's low-cost producers I had seen emerging so fast in China and many other new industrial nations. I became convinced that the explosion of digital connectivity was the answer.

At the time, the internet was helping to generate vast amounts of information about consumers and their desires and was creating vast fortunes for a new generation of entrepreneurs. Yet when in 1998 I went to visit one of the most celebrated management gurus of all time, he said something that struck me as weird.

The late Prof Peter Drucker, then 87, said: "The computer has yet to really influence American business." It sounded crazy when so much money had been invested in computing.

But he was right - as usual. He meant that the shape and structure and hierarchy of the corporation had not responded to the huge flows of information that companies now had at their fingertips about their customers, should they wish to use it. They had computerised their 20th Century shape, rather than responding to how the computer network was upending much of what they had been set up to do decades before. It was one of the many things they don't teach you at business school.

Companies remained stuck in the 20th Century when life was moving on. Organisations of all kinds still saw their users through the goggles of the mass market philosophy. They looked on their users as groups of people with similar desires, arrayed remotely "out there" in dozens of markets, each of millions of people. If they wanted to contact their consumers, they sent out teams of people with clipboards and questionnaires.

They seemed almost frightened of the people they were making things for. So they worked out what they could most easily make, and then they asked their marketing and advertising people to come up with the designs, campaigns and slogans that would enable them to sell the stuff they could most easily and profitably produce on their established production lines, or those of their suppliers.

Their customers were interesting to the corporations only to the extent they would buy what the businesses could supply. There was a huge disconnect between users and suppliers. But this is still the accepted driver of most of the modern economy, of the world we have created over the past 100 years.

It creates huge alienation and frustration in the workers, the managers, and the customers.

The transactional experience is one that almost everywhere raises the blood pressure of the participants on both sides, but particularly the buyers and users. And the relentless drive for cost efficiencies at the heart of it is driving the profitability out of this business model in the West.

Western companies simply cannot compete with the developing country producers who are using the mass production model faster and cheaper. This is Capitalism competing itself to death. To paraphrase Lenin, it is Capitalists selling the rope with which to hang them.

To try to rescue the developed world from this dilemma, my proposition was a new thing I termed the Heartbeat Economy, effectively almost a concierge approach to customers. To compete on something other than price, companies based in the West would have to escape from their preoccupation with mass markets and fulfil the precisely-defined individual requirements of their individual customers with breathtaking speed and efficiency.

This would be a worryingly intimate relationship for many businesses and organisations, but one which might provide a new kind of profitable and rewarding market place if they dared to be far closer to their customers' individuality than they had ever been before.

Joe Pine, an American management writer who has become the prophet of what is known as mass customisation, put it like this: "Customers don't want a choice. They want exactly what they want."

Taking the increased heartbeat as the symbol of all they want to avoid, organisations in this new economy would learn how not to raise the blood pressure of people who - in response - would learn to trust them.

I have seen this theory enhanced by lots of technology changes and collaboration over the internet, and advanced by the recent extraordinary rise of social networking as a new platform for interactivity that changes the way society behaves. The most vivid example of this social upheaval is something we did not know we needed 20 years ago, when it was invented by IBM: the smartphone. A revolutionary device, and one whose display and tools can be - and often are - absolutely individualised, so that no two phones are alike.

Configured from millions of applications and choices, their screens reflect their users' absolute individuality. They have rapidly become a part of their users' identity. But the 20th Century mass market of people, society and organisations persists, so thoroughly was it imprinted in us by Henry Ford 100 years ago.

Eighteen months ago in San Francisco, I had another of those rather rare encounters that changes how I think about the world. In a lofty office in one of the old converted warehouses north of Market Street, I found myself looking at a plastic bolt in a plastic socket.

Strong, ready to use - nothing remarkable about it. Except that both the bolt and the socket it was tightly screwed in to were "printed". It was a revelatory moment. I began to understand how 3D printing might affect our conventional world and bring us closer to a Heartbeat Economy. This was the upside-down world in action.

I was in the offices of a company called Bespoke Innovations, with a designer called Scott Summit. He had gone into partnership with a surgeon to make individualised artificial limbs, using a 3D fabricator. Bespoke can match an existing arm or leg, or design a prosthetic limb to be eye-catching in its own right.

The 3D printer works like a scanner, spraying one layer of metal or plastic powder on a surface, fusing it with a laser, and then repeating the process - just like a computer printer, but piling up a 3D shape layer by layer. When the fabricator has finished making the device, and the plastic or metal has been fused into solidity, you blow out the dust that remains from the assembly and there is the bolt snugly fitting into its hole. So, sophisticated joints and flexible devices are now printable.

In fact, printing is not quite the right word for the process. Enthusiasts call it "additive manufacturing" because of the contrast with the time-honoured way of making things - no more scraping away at metal to create shapes from it, or pouring plastic into expensive moulds. That has changed now. The compelling proposition is, if you can draw it, you can print it.

Spend an afternoon with a designer like Scott Summit in San Francisco and you begin to get carried away. I certainly did.

For the past 100 years, we have been taught to think that most things we use are best made in quantity on a production line. One-off things, bespoke, hand-crafted - all these "old-fashioned" ways of making things have become curiosities: quaint, fiddly, hideously expensive.

Not any more. As Summit, who started his career designing "one-size-fits-all" products to be sold in their millions, says: "We are about to see a real reawakening of this idea of unique products of all kinds."

The 3D fabricator can make something slightly different every time it makes an object, individualising it every time.

The individual customer can now get exactly what he or she wants at little or no extra charge compared with the cost of a one-size-fits-many model, and maybe even cheaper.

Bespoke Innovations claims that artificial limbs made like this may be one tenth of the price of ones made in the conventional way.

One particular cost saver is time: the gap from finished design to finished product is concertinaed into hours, rather than months as the 3D fabricator makes many components in to one united piece.

Of course there are currently limitations. Much of the stuff currently being 3D printed is modest and trivial - iPhone cases, plastic jewellery, spectacle frames.

But at Britain's biggest manufacturer, British Aerospace, they are printing highly individualised components for aircraft and satellites - not prototypes, the real thing.

Other companies are printing false teeth and there is no reason why they should not be done on the spot by dentists who fit them straight away.

It could be much bigger than teeth. At Loughborough University, I saw how they are learning to print houses in one go, using computer-aided design tools to direct a cement nozzle supported by a huge rig.

There is even talk of printing human organs as replacement for diseased worn out body parts and of printing personalised drugs at home. Huge regulatory problems present themselves, of course, especially when absolutely anyone can print a handgun, which is now possible.

But this 3D revolution could be bigger than a torrent of cheap new goods made to order. The mass production company gave new powers to the role of managers and foremen. But it debased the craft skills and turned human beings with very personal ideas and emotions into mere machine feeders. You hung your own personal ideas and ambitions on the hatstand when you clocked in for work.

Until now, that is. If individualised, personalised production catches on, it may radically reshape the corporation, with its divisions, baronies and management structures.

Designers and innovators will find themselves elevated in the business hierarchy, because they will be able to turn their inventions and ideas into feasible production without the interposition of the host of manufacturing experts hitherto required to turn designs into makeable objects.

Doing it for themselves: 'We wanted to explore, so we built our own underwater robot."

But this 3D idea is even bigger than that in its implications. Who needs metal presses costing hundreds of millions of dollars to make parts of equipment? Who needs hugely expensive moulds for plastic components, the place where hideous bottlenecks occur before new designs are sent to the factory?

Who needs factories? Who needs to transport all these manufactured goods all around the world when you may be able to make many of them just a stroll down the road from where you need them?

It is conceivable that a company may become merely a bright young designer or entrepreneur with a $1,000-laptop computer whose designs are produced at a 3D printing bureau on your local High Street.

This is edging towards something I think we may live to call Capitalism without Capital (trademark, all rights reserved). I am also sure that service industries will be swept up in all this, but I have not yet quite decided how.

Something is happening to us. And it is the new sense of the emergent individual that I think may be the profoundest change of all.

We may be able to get some grasp of how large an impact these new technologies may have on the way we perceive the world and how we then behave by going back more than 500 years to the arrival of another great disruptor of society, the printing press.

As a radio person, I'm very proud to be a member of one of the ancient City of London livery companies, the Stationers. A visit to their splendid hall in the shadow of St Paul's Cathedral sets you thinking about how the Stationers' traditional trade in pens and ink and manuscripts was utterly disrupted in 1476 by William Caxton's new printing press established just up the River Thames in Westminster.

The Stationers quickly embraced printers as members of the company and, eventually, the idea of copyright emerged from the Stationers' jealously guarded rights and privileges. And copyright created the concept of intellectual property, one of the main engines of the modern economy.

You get another overwhelming sense of print as a powerhouse of change in the elegant and slightly unlikely circumstances of a Renaissance courtyard house in the Friday market place in the Flemish port of Antwerp. I was there the other day and was again dazzled by it.

In the 16th Century, Antwerp was the trading centre of the world. In 1555 the Frenchman Christopher Plantin started a print and publishing business in the city which he and his in-laws ran for 400 years.

Remarkably, the building complex he created is still there, pretty much unchanged. There are 33 successive rooms of type, ancient wooden presses, and a library of the books they printed for the whole of Europe, sometimes at the breathtaking rate of one new title every week. Typeset and printed by hand, of course.

Plantin was the world's first industrial printer. The Plantin-Moretus Museum is an astonishing meeting point of commerce, civilisation - and power.

But the social impact of printing was far more profound than even the principle of intellectual property, and that social impact provides a possible parallel with the internet and 3D printing today. The printed book assembled a torrent of words on paper in a fraction of the time that a copyist could. This began to change the way the whole world behaved.

No longer were they handwritten volumes of knowledge chained up in libraries, dangerous knowledge firmly in the control of the church and those close to power.

Reading, which had until then mostly been done out loud in the courts of kings and the halls of monasteries, became a private pursuit. Scientific thought threw off the yoke of church and state censorship as books provoked dialogue and discovery. So did the ideas which writers, philosophers and poets put forward - human sensibility itself began to change.

Effectively, printing changed the relationship between men and women and their universe, their surroundings. Nobody knows who first said it, but there is no exaggeration in the resonant phrase about the alphabet moulded into sticks of metal type: "With 25 lead soldiers I will conquer the world".

This sort of thing does not happen very often. I think it is happening again now, but it is very early in its development. The word for the printing done in the 15th Century is "incunabula". It means the "swaddling clothes" of a baby industry.

I would like to propose that our new internet age may eventually be seen to be living through a disruption of the human sensibility on a par with the invention of printing.

There are other candidates for this disruptive role, including the automobile, the aeroplane or broadcasting. But the internet is more profound because of the power it endows the individual user - the power of imagination, invention, collaboration and market-making.

But it is difficult to see when we are in the middle of this great disruption. We are still at the incunabula, the infant stage of the great internet upheaval.

And as the prophet of communications Marshall McLuhan said, we tend to look at the future through the rear-view mirror of the past. The first car was a horseless carriage. Early radio was the wireless.

But for richer, for poorer, for better or for worse, the world is being turned upside down. And we are just beginning to see what these possibilities are.

Illustrations by Robin Chevalier | eastwing.co.uk

Listen to the World Turned Upside Down by Peter Day on BBC Radio 4's Archive on 4 programme, Saturday 12 October at 20:00 BST. Or listen to it on the Archive on 4 website. Download Peter Day's World of Business podcasts here.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external