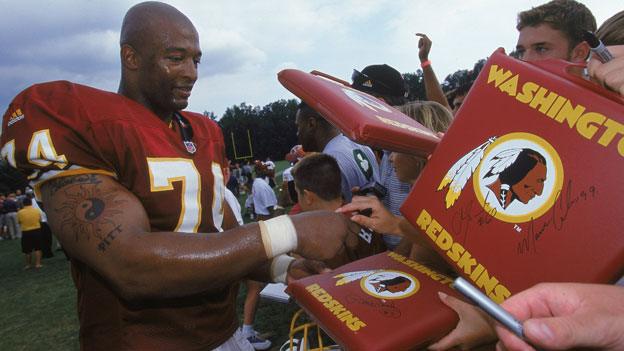

Washington Redskins: Time to change the name?

- Published

Pressure is mounting on the Washington Redskins to change their name because of the offence it causes Native Americans. But will a club steeped in tradition ever buckle?

It's one of the most famous names in American sports, with a logo recognised the world over.

But even fans of the Washington Redskins are facing up to a belief that it might all have to change.

For many years, some people have questioned why the football team has a name that Native Americans find offensive. And now the campaign is building momentum.

Protests have been organised to greet the team at their away game on Sunday in Wisconsin, which will also mark the start of a season-long ad campaign on the local radio airwaves in every city the team will visit.

More and more journalists are refusing to use the name, the most recent refusenik being Christine Brennan at USA Today, who announced the move, external on Thursday, thereby joining Peter King at Sports Illustrated and Mike Wise at the Washington Post.

Attitudes are also changing at grassroots level. A high school in upstate New York changed its nickname to "Hawkeyes" in April after students complained the longstanding "Redskins" nickname was offensive. A month later, members of Congress formally asked the league to consider a name change.

Players have remained silent but not former players. Washington football great Art Monk said no-one should question why Native Americans feel this way about the name.

The radio ad campaign which begins on Sunday is aimed at educating listeners in every city that hosts the team why the word offends, and is organised by the federally-recognised tribe Oneida Nation.

"It's derogatory, it's dehumanising, it's degrading and it's high time this was addressed and changed because it gives the wrong message to the world," says its leader Ray Halbritter, who says he was called a redskin at school.

The word was used when his ancestors were forced off their lands at gunpoint, he says, and when their children were taken from their homes and forced to go to boarding schools.

"So it's very hurtful for us to hear. The English Dictionary says it's an offensive term and it is. There is no grey area. It's bad for the image of the league to be using a racial epithet and making money out of it."

The word was first used by Native Americans themselves, to distinguish themselves from Europeans, says Ives Goddard, senior linguist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC.

Extensive research by Goddard, outlined in his paper entitled I Am A Redskin, external, suggests the colour red was being used to self-describe natives in the Illinois region in the 1720s. With very few primary colours identified to them, says Goddard, red would not have resembled the same red we think of today and could, for example, have meant earth-brown.

The word "redskin" was used in 1769 by "Old Sachem" Mosquito, a French Maringouin, when he said in a letter to Lt Col John Wilkins, translated first into French and then into English: "I shall be pleased to have you come to speak to me yourself if you pity our women and our children; and, if any redskins do you harm, I shall be able to look out for you even at the peril of my life."

It then appears in English print about 50 years later, in discussions between President James Madison and various tribal chiefs in Washington. French Crow pledged obedience and said: "I am a red-skin, but what I say is the truth."

"It's being used by an Indian and the idea that it would be derogatory doesn't make any sense," says Goddard, who says the belief that the word referred to the skinning of Indians for bounty has no basis.

"The Europeans as soon as they encountered this have to explain it, so it's not something they dreamed up."

The idea that it was derogatory doesn't really crop up until well into the 19th Century, he says.

It was adopted by the football team in 1933 when co-owner George Preston Marshall renamed the Boston Braves the Redskins, and the name followed the team to Washington.

Many US sports teams were named after indigenous peoples, adopting logos and mascots to match. But as the years passed there has been an increased sensitivity to those that were thought to be crude or stereotypical. The Braves, Chiefs and Indians have survived but other names haven't - in the late '90s, Miami University in Ohio ditched Redskins for RedHawks.

In Florida, the state university came to an agreement with one of the Seminole tribes to continue to use the nickname and imagery.

Fan groups in Washington were reluctant to comment on the name controversy, but on online forums some defended the name, saying there was nothing offensive in it, while others seem resigned to change. There were also voices in support of change.

A nationwide poll, external conducted in March suggested a majority of Americans support the current name, although many of them accept it is offensive to Native Americans.

For lifelong Redskins fan Denise Perry, from Maryland, the word represents the Washington family, team spirit and the unifying atmosphere of match days.

She understands there are negative connotations too but adds: "Calling it anything else would take away from the meaning and history of the Redskins I grew up with. If the owners ever considered a change, I would join the protests."

One protracted avenue of change began in 1992, when a lawsuit challenged the Redskins trademark. The case ended in 2009 after the Supreme Court declined to review a federal court's decision to toss the lawsuit out on a technicality.

But earlier this year, the issue picked up again, when 10 members of Congress wrote to the league and to Dan Snyder, the team's owner, asking for a change because the name was a "racial, derogatory slur".

In response, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell backed Snyder and the name, but this week he seemed to soften his stance, saying in a radio interview that it's Snyder's decision but added: "If one person's offended, we have to listen."

The club refused to comment on the issue, but earlier this year Snyder said: "We'll never change the name. It's that simple. NEVER - you can use caps."

But the issue may be forced on him, says the Washington Post's Mike Wise, who stopped using the name in his columns in March after being asked to by Native American groups. He thinks the name will change within five years, because opposition is reaching a critical mass.

"I've been in Washington for almost 10 years and I've never seen this much fervour and sustained interest in this. I think it will be taken out of the hands of the owner at some point."

Any action that hits the NFL's bottom line, like a nationwide boycott of team sponsors, could force the NFL to act, he says. He thinks the issue has arisen again this year because for the first time in 20 years, the team is being described as potential Super Bowl champions, with star player Robert Griffin III to the fore.

"I can see how a lot of people in Washington, including the owner, grew up loving the team and never used the word in a disparaging way towards American Indians," he says.

"I can see that's part of their history and I don't think they're racist because they use it. But why can't the owner and the most ardent fans of the name put themselves in the shoes of someone else?"

About 2-3,000 high schools, middle schools and college schools have changed their names but the professional organisation refuses, he says. His personal choice for a new name is Washington Warriors, with a logo depicting a proud veteran.

He calls his own act of protest a small gesture of respect, and instead he refers to the "Washington team" or "[coach] Mike Shanahan's team".

Or more creatively, "Robert Griffin III and friends".

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external