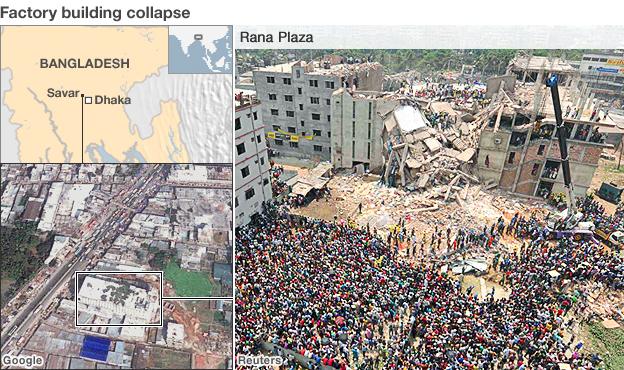

Dhaka factory collapse: No compensation without DNA identification

- Published

Samsun Nahar with her daughter's photograph

Earlier this year a Bangladesh clothes factory collapsed, killing more than 1,000 people. Five months later, many of the dead have yet to be identified - prolonging the anguish for relatives, and denying them the right to compensation.

A summer has passed since the Rana Plaza complex crashed to the earth. Plants are creeping over the tangled debris. Steel cables have rusted. Rolls of blue and cream fabric have gone mouldy. A fading pair of jeans hangs from a jagged piece of wire.

A stone memorial remembers the 1,133 garment workers who died.

But hundreds of families who lost a mother or a daughter never have never been able to prove it to the authorities' satisfaction.

The US offered relatives DNA testing kits, and samples have been collected - but Bangladesh doesn't have the computer software to match those samples with the dead.

Every day Babul Soiaal walks to the Rana Plaza site, with a roll of papers and documents in his hand - and a small passport photo of a woman in a blue headscarf.

Babul Soiaal with a photo of his wife, Shahida

It is his wife Shahida. She's still missing, and she's probably among the nearly 300 people buried without being identified. Only when, or if, she is identified will the authorities provide financial help.

Soiaal has Shahida's payslip to prove she worked in the Rana Plaza - but that's not been enough to persuade officials to pay up.

"I have made a copy of these papers and given them to the government and other concerned bodies and I said if you have any doubt you can send an inspection team to our home town and they will find that she is still missing," he says.

"I have five children. I have lost my partner. If the government would help us then we will find some way, but I don't know what will happen to me."

Friends have been lending Soiaal money to pay the rent, which his small income from odd jobs will not cover.

But what he really needs is for his wife's body to be identified by a DNA test. Then he might receive from the government the equivalent of £13,000 ($20,000).

Because of the software problem, few DNA identifications have been made.

Among the high street brands which once bought garments from factories inside the Rana Plaza are Primark, Matalan and Bonmarche.

Primark has pioneered its own emergency payments scheme, giving each of the victims' families 15,000 or 16,000 Taka - about £130 ($200) - and announced last week it will pay a second tranche.

In Samsun Nahar's case, the first instalment ran out months ago.

Like Babul Soiaal, she comes to the Rana Plaza ruins every day, hoping someone will tell her what happened to her daughter, Eeni Begum. All she has left of the beautiful, earnest 18-year-old is a passport photograph.

"Every day I feel I'll find my daughter, but it doesn't happen," she says.

Yanoor, 14, wants to provide for her family again

"We are very poor - it was difficult to keep her at school and we put her in the garment factory. She loved fashion. She was my beloved one. Without her I feel lonely. Everything seems empty."

Even some of those in hospital - whose missing or broken limbs provide physical evidence that they were in the collapsed factories - complain they've been forgotten by the authorities and the Western brands.

Fourteen-year-old Yanoor who, under the terms of an industry agreement, should not have been working at the factory at all, has needed several operations after her legs were crushed by falling beams.

She too has had no compensation. She is eager to get well so she can earn for her six brothers and sisters, and her father. Her mother died in the rubble.

Among those children working illegally in garment factories today are some who have been forced to seek work because their parents were hurt or killed in the Rana Plaza tragedy.

One 13-year-old, who we will call Ruma, says she gave up school and got a job in a factory as a seamstress, because her mother was hurt in the building collapse, and is now unable to walk.

There are about 20 teenagers working in the same factory, she says, all of whom have been instructed to tell any visitors they are 18.

"My mother is very sick so I had no option," she says. The family relies on the 4,400 Taka (£36, $57) she earns each month.

The Bangladeshi government says it is giving Rana Plaza victims and their families compensation and donations from an emergency relief fund, but the country can't afford to provide a long-term safety net.

Commerce Minister Ghulam Muhammed Quader admits that for some life is getting worse, not better, since the tragedy struck.

"I don't blame them for their worries. The problems are overwhelming for the government and society," he says.

"We are a resource-constrained country. Even if the government gives full compensation it is just a stopgap. What we're trying to do is rehabilitate someone in the family so they stand on their own feet."

The government is giving limited money to hospitals where injured people are learning new skills, such as IT.

The garment industry, meanwhile, says it's offering people alternatives to factory work, but many of the injured aren't well enough to leave hospital yet.

Mohammad Shahidullah Azim, vice-President of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, says they carefully monitor factories and fine any owners caught employing children.

The Rana Plaza collapse was the worst industrial disaster in Bangladesh's history. But for hundreds in Dhaka, the tragedy is only just beginning.