Cory Booker and me

- Published

The US has a new senator, Cory Booker, who swept to an election win in New Jersey on Wednesday. The Democrat is tipped for great things by his supporters, which comes as no surprise to those that knew him at university.

In Marshall Curry's Oscar-nominated film about Cory Booker's unsuccessful 2002 campaign to be mayor of Newark, New Jersey, he shakes hands with a girl while out canvassing.

She turns to the documentary-maker's camera and says: "Smell my hands 'cos I just touched Cory Booker.

"He smells like the future."

Now Cory Booker has earned a Senate seat after beating Republican Steve Lonegan this week, it's worth recalling how much star quality he had when he was at The Queen's College, Oxford, in the early 1990s.

He was a Rhodes scholar with a masters degree from Stanford. I was five years younger and just starting out on my first degree.

Booker was such a striking figure that you always noticed him. I've never met anyone with as much charisma as Cory - he could make you feel better about yourself with a nod from the other side of the quad. You know when you see charisma in someone - the atmosphere changes when they enter the room and you want to get to know them.

I had signed up for the university's inter-college American football tournament. It was flag football, so instead of jumping on opponents to tackle them you have to pull a velcro flag off their belts.

Booker had been a player of national standard in high school and then played for Stanford University, so was just the man to teach us the game.

But he had a job on his hands, because we were dreadful. It turns out that a good American football team needs to have at least one player who can throw and one who can catch. We had Booker, who could do both, but that's not enough.

We lost all of our games, but the preparation was extraordinary. He showed us a particular play, which he said Stanford had used to "whip Notre Dame's ass". The rivalry between the Fighting Irish and the Stanford Cardinal makes the annual game between them a grudge match. So it made for a surreal experience playing in the middle of a park in Oxford, using tactics that had been devised for a game played in front of 90,000 people.

Before our first game, Cory gave us a team talk. Team talks are the bread and butter of great sporting films, but I'd never been on the receiving end of a proper motivational talk before.

Not an Oxford park... Booker was used to the glamour of Stanford

We all sat around him as he told us a story, about a time when he was playing college football and another player was questioning whether he wanted to win enough. I think it may even have been a player he admired from another team.

In the denouement of the story, this enormous player sat on Cory's chest (and he's not a small chap himself), stopping him breathing.

We were gripped by this narrative, as Cory, without raising his voice, gradually got to the point in the story where he was about to pass out and the other player told him that he would not be a great player until he wanted to win as much as he wanted to take a breath.

It was extraordinary - I wanted to win that game more than I've wanted to do anything.

In a pretty hopeless team, I was easily the worst player. But in a game that we lost, like all the others, I had my moment.

I was playing on defence when the person I was supposed to be marking got many yards away from me and prepared to catch what would have been a touchdown pass.

I ran and took a huge, goalkeeper-style dive and got my fingertips to the ball. I remember watching it dribbling over the sideline as I landed in a heap on the floor.

Cory dragged me up from the ground with his hand over my eyes, so I could hear the shouting around me but not see the team. He generously described it as the greatest play he'd seen.

I've played a lot of pub football and village green cricket since then and had some pretty exciting moments, but I would have no hesitation in describing that as the greatest sporting moment of my life.

It's not because there was much at stake - I think we were already way behind in the game. It was exciting because of the atmosphere and motivation around the team that Cory had created.

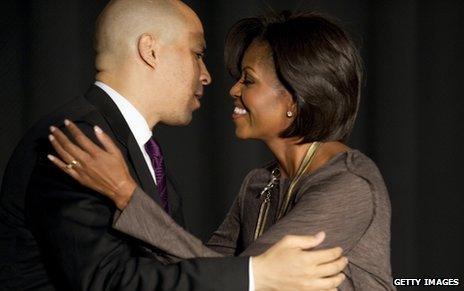

Booker has supported Michelle Obama's obesity campaign

As mayor of Newark, Booker has been credited by his supporters for overseeing a drop in violent crime and reducing the city's budget deficit. But he also has a national profile thanks to his prolific and savvy media appearances.

His clever use of social media was most notably demonstrated when he was tweeted by a woman whose elderly father needed help shovelling snow from his drive. After a brief exchange, Booker himself turned up at his home to offer a helping hand. On another occasion, he assisted one of his Twitter followers to propose to his girlfriend.

An all-action reputation was sealed when he rescued a woman from a burning building and then a year later rescued a dog in frozen conditions. He also took in people temporarily homeless from Hurricane Sandy.

But there have been bumps in the road. Eyebrows were raised when the 15-year-old son of CNN chief Jeff Zucker became an advisor at a tech start-up Booker co-founded with the help of some high-profile investors in Silicon Valley. Booker sold his stake in the firm last month.

No such criticism at Oxford, where Cory had a great effect on Rabbi Shmuel Boteach, who was the representative in Oxford of the chasidic Jewish movement, Chabad-Lubavitch. He'd set up a rival Jewish Society for Oxford students called the L'Chaim Society.

In practice, it was seen by students as a club for American post-graduates, which had very impressive speakers. But it was still quite a shock when Rabbi Boteach appointed Cory, a 6'3" black Baptist, to be president of the society.

The rabbi said he'd given Cory the job because he was the best person he knew. Cory would give talks at the society's Friday night dinners about that week's Torah portion and apparently has been studying biblical tracts with Rabbi Boteach ever since.

When Cory was running to be mayor of Newark, his opponents criticised him for not really wanting that job, saying that it was just a stepping stone to higher political dreams.

It says a lot about him that in the Senate campaign, his opponents have been saying the same thing.

Talking to other contemporaries from Queen's he seems to have been widely liked and admired. He volunteered for the charity Nightline, which gives emotional support to students, as well as doing some voluntary work in a school on the nearby Blackbird Leys estate.

We were all wrong about him at college, though. We were convinced he'd be the first black president, and he missed that boat.

But I wouldn't bet against him in a future race.