Why do so many Americans live in mobile homes?

- Published

An estimated 20 million Americans live in mobile homes, according to new Census figures. How did this become the cheap housing of choice for so many people?

"From the state where 20% of our homes are mobile 'cause that's how we roll, I'm Brooke Mosteller, Miss South Carolina."

Not the usual jaunty PR message you expect to hear at Miss America. And Mosteller caused a minor storm, external for presenting what some South Carolina natives felt was a negative slight on the state.

A few days after her comments, US Census figures confirmed that her state did indeed have the highest proportion of mobile homes - also known as trailers or manufactured housing - though the figure is closer to 18% than 20%.

Mobile homes have a huge image problem in the US, where in many minds they are shorthand for poverty. But how accurate is this perception?

Comparing the top 10 mobile home states with the 10 most deprived states suggests a loose correlation. South Carolina is not among the 10 poorest by income, but there are eight states, all southern, that appear in both lists.

"Not everyone who lives in a trailer park is poor," says Charles Becker, a professor of economics at Duke University, and one of a handful of academics nationwide who has extensively studied the subject.

"And there are parts of the country, like Michigan, where living in a mobile home community doesn't have the stigma it does in the south. You also have retirement communities in Florida where people aren't poor at all."

Mobile homes make up 6.4% of the US housing sector and there are 8.5m of them, down slightly on 2011, according to the US Census. The number of occupants is not recorded but it's estimated to total about 20 million.

According to the Manufactured Housing Institute, about 57% of the heads of mobile home households are in full employment and another 23% are retired. But the household median income is only a little over half the national average.

West Virginia has the third highest proportion of trailers in the US. And in the rolling hills near the Shenandoah River, amid the country roads made famous by John Denver's signature song, there are any number of mobile home parks, usually tucked away from view, up the hill or round a corner.

The 22 units at Oak Haven Mobile Home Park outside Martinsburg are neatly arranged, 25ft apart, nestled in a dip just the other side of Needy Road from the Bakers Height Baptist Church, which stands alone on a wide expanse of green fields.

The homes don't look like trailers in the conventional sense and inside they're spacious with 2-3 bedrooms, a fitted washer and dryer, two bathrooms including an oval tub, and an island breakfast bar in the kitchen.

For Michael Breeden, 27, picking a mobile rather than fixed home a year ago was all about freedom. "I know I could have got a [foreclosed] house if I wanted to but we can move this to where we want and if [house-owners] want to move they're stuck."

It's been a largely happy 12 months in the 80ft home for his 23-year-old girlfriend Samantha, their 17-month-old baby Kelli Lynn and Breeden's mother, Mary McGee.

It's quieter and safer than their previous rented home but it's a stepping stone - they have a "five-year plan" which involves buying some land and then moving the home, at a cost of about $2,500 (£1,560), into the mountains, "where there's a view".

Breeden, who works at a printing plant nearby, pays the park owner $325 a month for lot rental, rubbish collection and water supply. There's also $150 to pay monthly for electricity, $60 property tax, and $220 to Samantha's parents who lent them the $16,000 (£10,000) to buy the home.

Several of Breeden's neighbours say how much they enjoy the tranquillity of Oak Haven. The site was built in 1959 by Frank Rouss, who cleared all the oak trees away and built 28 trailers on the site, while also raising 11 children.

Most of the homes here are rented and there is not a single piece of rubbish discarded anywhere, because the rules are strictly observed - no music outside the homes and nothing left on the lawns.

Life at Oak Haven

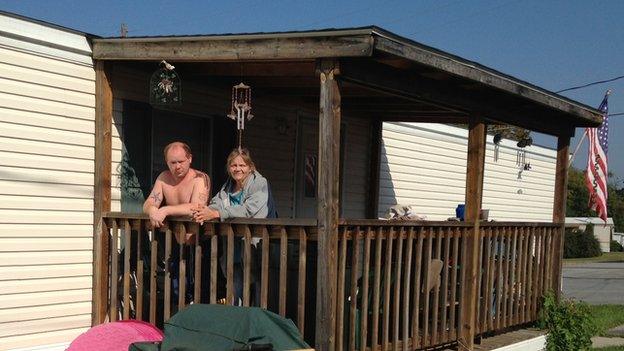

"It's very quiet and always clean," says bartender Sue Bobbitt (above left with partner John Dimmick), who moved in a month ago. "That's one of the main things I was looking for. We've lost a lot of space because I had a three-level townhouse but there are no parking problems." They say they'll stay in their first mobile home, which is rented, for 1-2 years and hope to buy a place in the countryside. Mobile? "Perhaps."

"My father was a railroad man and I was raised on a farm so I always collected antiques," says Butch Comer, 66 (above with partner Eleanor), pointing to an array of collectibles around his bedroom. "I love it because you can come out and sit in a chair and no-one is raising hell."

Gary Miller, 72, is poking around in his shed, behind the 70ft home where he has lived for 27 years. "It's quiet. There's no bunch of drunks hanging around having parties. After the five kids got off on their own, we moved down here. It's the first property we ever owned. I would rather live in a house, it seems safer. In storms, you have to watch these things but we don't have that many big ones."

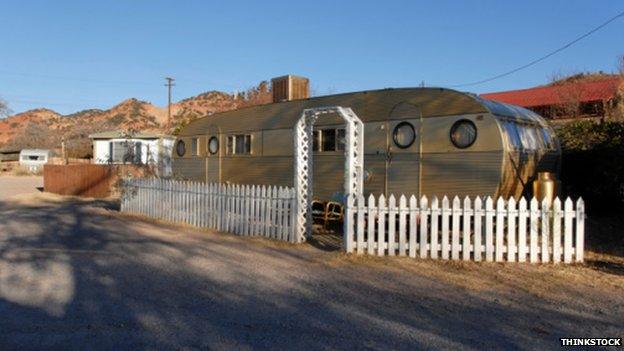

The homes at Oak Haven are typical in that they are rarely moved but the first mobile homes were true to their name and towed.

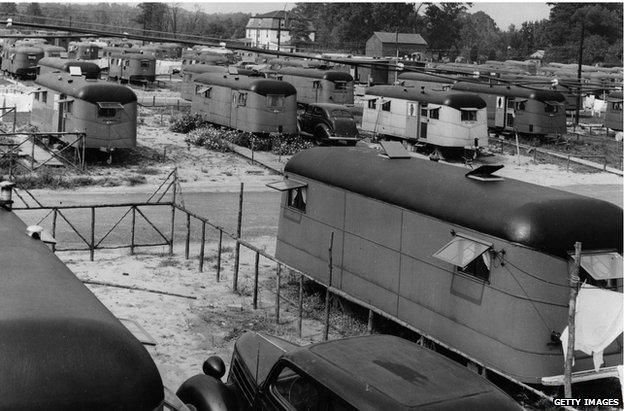

"In the Great Depression in the 1930s, people started living in trailers which were designed for travelling and vacationing but out of necessity, people started to make these tiny mobile units their homes," says Andrew Hurley, author of Diners, Bowling Alleys and Trailer Parks.

"They started parking them on the outskirts of cities and that's when they become associated with working class and impoverished people."

There was institutionalised discrimination, he says, as federal-backed mortgages were denied to owners of mobile homes, while zoning laws forced these communities to the very outskirts of towns and cities.

The 40s and 50s were their heyday, helped by the innovation of "double-wides", which meant they came in two separate units and formed a larger home.

"But the idea of permanent living in a mobile home didn't really catch on and by the 60s and 70s the private housing industry had caught up with demand so people that could afford to move out gave up their trailers for a more conventional suburban type of housing," says Hurley.

Trailer park in Baltimore in 1943

A tightening of credit since the recent crash has slowed sales of new homes but the market has been strong at the top end. Paradise Cove in Malibu is a trailer park inhabited by actors Pamela Anderson, Minnie Driver and Matthew McConaughey, where homes fetch up to $2.5m and come with marble floors.

If your budget won't stretch to that, there are communities like Parrish Manor in Raleigh, North Carolina, which is more like a health retreat - there's a football field, a community garden, playgrounds, a walking trail, picnic area and sports programmes for children. There's even a car maintenance shed.

But the US poor are still more likely to live in a trailer than the typical American. And they remain a largely US phenomenon. Although mobile home parks are found in Canada and there are sites for static caravans in the UK, they are not found in the same number.

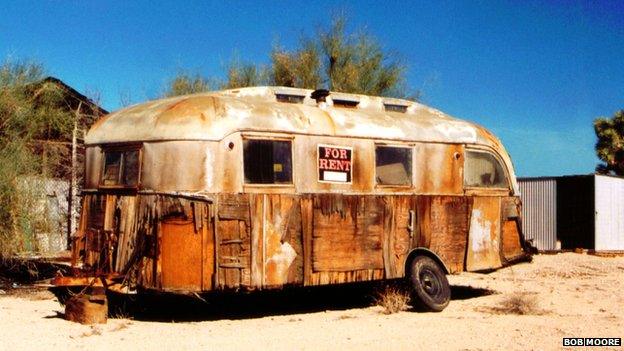

Some parks, like this one in Thermal, California, are very deprived and tough places to live

"Housing in the US is cheap and land is cheap so it's easy to do minor modifications to provide electricity, some form of sewage and water supplies, even put in a clubhouse and a swimming pool. It's cheap to do all this in the US but in Europe it's prohibitively expensive," says Becker, speaking during a break at a conference in Illinois for trailer park owners.

"And public transportation is better in Europe so there's a comparative advantage to the poor living in a central urban area whereas in the US manufacturing is located up and down major highways so it's much easier for people with these jobs to not want to be in central city areas."

There's also the American ethos of private home ownership that runs very deep, says Hurley, so the alternative of a rented city apartment is not always attractive.

"And there's the American love for freedom and mobility. Even though in reality mobile homes are never really very mobile, it's the idea that you can pick up and leave any time if you didn't like your circumstances, in a way you can't with a house."

Plus there's a policy issue, he says - limited housing options in the US for low income people. The threshold at which they're eligible for subsidised housing is much higher than in European countries so people that might live in a council house in the UK don't have that opportunity here.

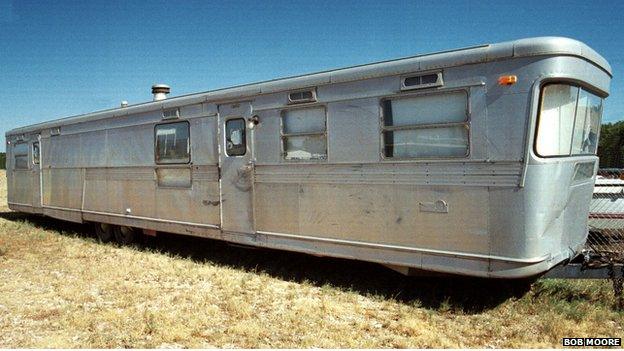

Bob Moore began photographing abandoned trailers 30 years ago, having lived in mobile homes for much of his life. This one in Yucca Valley, California, made the front of his book, Trailer Trash.

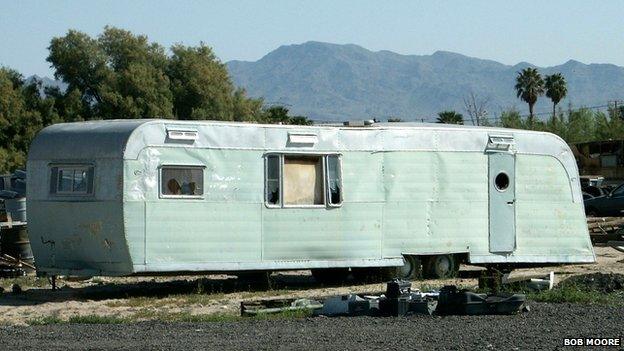

"I just liked the things and since I had been 'trailer trash' for a large portion of my life, it just seemed to be interesting to see these once former homes sitting lost," says Moore. This one is in Amarillo, Texas.

"Many people look upon the term 'trailer trash' as pejorative and take offence, which is one of the reasons I have attempted to turn it around with both the title of the book and my own pride in being 'trailer trash'."

It's inevitable that a world largely hidden from view would suffer from misconceptions, says John Fraser Hart, co-author of The Unknown World of the Mobile Home, but they are nicer and more spacious than people realise. He thinks their image as dens of sex, crime and hard drinking is partly due to television.

The Canadian series Trailer Park Boys is one example, and in films like Boys Don't Cry, bad things happen in these places, which aren't just on the edge of town, they're on the edge of civilisation. This seedy image has been further enhanced by depictions in pulp fiction novels.

And such negative representations are expressed in one insulting term - "trailer trash". But interestingly, some of the residents at Oak Haven think there's some truth in the stereotype.

"A lot of the trailer parks, there's a lot of trouble, they're so cramped together, and you have a lot of low income people moving into trailers," says John Dimmick, who has recently moved into a rented mobile home with his partner Sue and their terrier Wilbert.

"With that comes other problems. They don't want to maintain their properties. That's where the term trailer trash comes from. But we don't consider that [applies] here, this is just like a park.