The making of Angela Merkel, a German enigma

- Published

Angela Merkel has won a third term as German chancellor, in an election that will influence the future of much of Europe - Britain, France, Spain, Italy, Greece and many other countries. Her skill at coalition-building will be tested again, as her conservative Christian Democrats came just short of an overall majority.

For every country in Europe, it's all about the economy. Across the continent, people are still battling with the twists and turns of the financial crisis. And wherever you are, economic recovery depends heavily on how Angela Merkel treats the next stage of the crisis: these days, most roads lead to Berlin.

That's why it has long seemed to me that one of the most important political reporting jobs right now is to try to understand Angela Merkel better. But Mrs Merkel is an unusually private and reticent politician - there is no exhibitionism and grandstanding. Even for Germans, she's a hard woman to know.

She didn't want to do an interview ahead of the German elections, and certainly not in English - even though she speaks it quite well. But we've spoken to a range of her friends, her political allies and her critics. We've delved back into to her upbringing in the pretty East German town of Templin, some 50 miles from Berlin, and spoken to childhood friends and student mates who knew her at a time when politics was more dangerous and tricky.

Merkel was actually born in Hamburg, West Germany. Her father Horst, a Lutheran pastor, moved the family to the East in 1954 when Angela was just a few weeks old.

As a politician, Merkel has never been overbearing when it comes to her religious views, but it's clear that her father's position in the church had a deep influence on her - creating a powerful moral compass.

Her childhood was also shaped by the Cold War - Merkel's Socialist father held politically charged gatherings at his seminary and as she grew up, vigorous debates rang around the dinner table. The young Angela had to learn to keep her cards close to her chest for fear of drawing the attention of the Stasi, the secret police.

Being unable to openly express your opinion in East Germany affected people in different ways.

An old school friend of Merkel's, Hartmut Hohensee, compared it to lapsing into "a sort of paralysis, just hoping winter will pass and the flowers will begin to grow eventually". Merkel's political flowers would begin to grow - but not until 1989, after the Berlin Wall was toppled.

What Angela Merkel did when the Berlin Wall came down

The fall of the Wall produced a maelstrom in German politics. Cafe conversations became street protests; movements became political parties; individuals tried to take control of their country for the first time. It was this world that Angela Merkel decided to enter, aged 35.

Merkel, who has a doctorate in quantum chemistry, stood out from the rest in that political world.

"She didn't seem to care about her outward appearance at all," says Lothar de Maiziere, who went on to be East Germany's last prime minister. "She looked like a typical GDR scientist, wearing a baggy skirt and Jesus sandals and a cropped haircut."

To the surprise of many, the East German woman brought up under Communism joined the overwhelmingly male and patriarchal Christian Democrats. In late 1990 she became a member of the Bundestag for the CDU, the largest party in West Germany, and began her rise to the top.

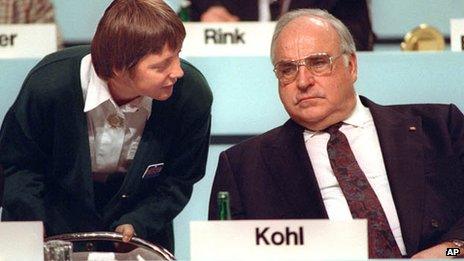

Germany's Chancellor Helmut Kohl wanted someone female, quiet and a former East German for his first post-reunification cabinet. De Maiziere recommended Merkel. Beginning as minister for women, she moved slowly up the ranks, becoming minister of the environment.

But in 1999 the quiet girl from Templin stunned everyone. It emerged that Helmut Kohl, who used to call her his "Maedchen" or little girl, had been putting donations into a secret slush fund which he'd used to reward his friends.

Nobody seemed prepared to confront Kohl but Angela Merkel refused to follow the pack. In a front-page piece in a leading conservative newspaper, she denounced her former mentor and called upon him to resign. It was a stunning act of political patricide and set Merkel on a trajectory towards the top of German politics.

"One of the things people don't always understand about her is she's… actually a ruthless political operator," says Jonathan Powell, who got to know her when he was chief of staff to the UK prime minister. "The way she dealt with all of her rivals in the CDU was extraordinarily Machiavellian from that point of view. She would get rid of them in a switch of an eyebrow."

Angela Merkel became chair of the CDU in 2000 and Germany's first woman chancellor five years later.

The defining moment of her eight years as leader so far came with the eurozone financial crisis. Greece revealed an enormous - and unmanageable - public debt. And it soon emerged that other countries were in similar dire straits. But as Europe waited to see if Germany would agree to bail out the struggling members of the eurozone or force them to sort out their own problems, Merkel was criticised for reacting too slowly.

German election explained - in comic-book form

Caution and consensus, however, have always been hallmarks of the Merkel machine. "You can only manage such a crisis if you take a lot of people along the way," says Ursula von der Leyen, who has worked in every one of Merkel's cabinets since 2005. "Angela Merkel always knew where she wanted to end up, but she took time to find a way which everybody could go along with."

I don't claim that I have "cracked" Merkel - she is an abnormally complex and multi-layered character, unlike anyone else I can think of in world politics.

Quite a lot about her story seems to echo Margaret Thatcher's. Merkel comes from the edges - East Germany, rather than Lincolnshire - and was brought up by an abnormally self-certain and pious father. Something of a loner, she became quite a serious scientist before choosing politics.

Inside her party, she was picked up as a useful female talent by a somewhat patronising mentor - Kohl, rather than Edward Heath - and surprised everybody by her ruthlessness in ousting him, and eventually taking power herself. Like Thatcher, Merkel is a ferociously hard worker, excellent on the detail and a wily political operator.

Yet the differences matter much more than the similarities. Coming from her East German background she believes in social solidarity and working with trade unions; in a coalition-based political system, she is a mistress of consensus and, when it suits her, delay.

Our ignorance of this, the most important female politician in the world, is little short of shocking. Angela Merkel has mattered much more to us and the full European story than perhaps we've realised.

Is she going to remain as crucial in the future? Probably. Now she'll have another chance to secure her legacy.

Watch The Making Of Merkel with Andrew Marr on BBC Two at 20:00 BST on Saturday 21 September or catch it later on the BBC iPlayer.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external