Is Walter White one of TV's truly evil characters?

- Published

(Spoiler alert: Multiple key plot details revealed below)

Breaking Bad, which is about to reach its finale, has provided a talking point for fans and philosophers over the nature of a man's descent into evil, writes Dr David Koepsell.

Walter White is one of a number of morally reprehensible characters at the centre of modern TV dramas.

Like Tony Soprano, the New Jersey mob boss, or Frank Underwood, the political schemer in Netflix's recent remake of House of Cards, we are drawn into the character first by his simple sympathy and appeal.

Unlike super-villains in comics, these anti-heroes are all too human, all too recognisable. They are like people we know, even like each of us in some way. Tony Soprano displayed his vulnerabilities to his shrink, Frank Underwood tells the audience his inner secrets, and Walter White is simply an "everyman".

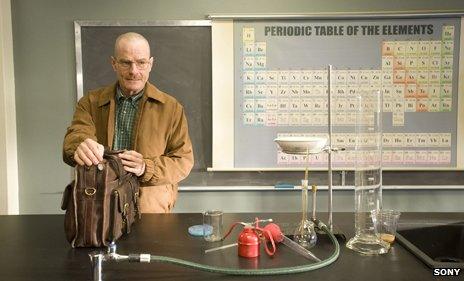

More than perhaps any of these other "bad men", Walt's transformation from meek chemistry teacher to murderous drug kingpin has provoked water-cooler discussions, blogs, passionate articles and forum discussions online.

We meet him working a second job at a carwash to make ends meet. He has a child on the way, and is in a dead-end thankless job as a high school teacher in the troubled economy of the American Southwest. He sums up a certain early 21st Century experience to which all too many can relate.

The origin of the term "everyman" was an English morality play written in the 15th Century. Morality plays were not-too-subtle attempts to convey moral lessons (generally sanctioned by the Church) to the masses. In Everyman, the protagonist was made to take account for his deeds in life, to tally the good versus the bad, as an accounting of his soul in the afterlife. Breaking Bad is this tale re-told and with a twist.

Our reaction to Walter White throughout the series is telling, and proves that the show is meant as a morality play. The genius of the trajectory of the series, and its manipulation of viewers, can be seen in how Walt's evolution has been shown, and how we were led along the primrose path.

Most of us sympathised with Walt early on, cheered his successes, and fretted over his failures.

Even as he killed gangsters Emilio and Krazy-8, and helped lead to his DEA agent brother Hank's killing of Tuco, we wished he would succeed, to build a more secure future for his family, to defeat the drug lords he first set himself against.

The science geek defeats the gangsters - what could be more compelling or sympathetic? That sympathy began to slip for many with the more morally ambiguous death of Jane. Walt allows her to die, choking on her own vomit while strung out on heroin with Jesse Pinkman, his partner in crime and former pupil.

Walt's conscious decision not to save Jane when he could led to 167 people dying on a plane because Jane's dad's grief interfered with his job directing air traffic. Jane's dad's suicide was the final catastrophe from that chain of events, and is again somehow Walt's fault.

Those who were still left sympathising with Walt, or who might have been on the fence, may have seen redemption through Walt killing the two gangsters about to kill Jesse in a later episode. But for most, Walt lost us completely when he ordered the cold-blooded murder of mild-mannered Gale, Walt's protege in crystal meth mogul Gus Frings's lab.

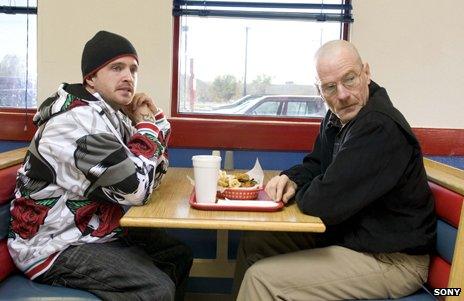

Walt with Jesse, his partner in crime

The series in its second half becomes a downward spiral of corruption, and there is little hope now of Walt's redemption. The balance sheet has tipped far too heavily against him.

His son Walt Jr sees this, as does Jesse. They hate him as we should. These two young men can cast nearly untarnished moral judgement on Walt, as could Hank.

Even Walt knows that there is no hope for moral redemption and the best he can do is to save some innocents as he hurtles toward his demise. He refuses to be complicit at least in Hank's death and vetoes, ultimately, Jesse's, though he insists on hurting him with the revelation of his role in Jane's death.

Philosopher Kimberly Baltzer-Jaray has argued that Walt's actions are authentic, in the sense that Sartre and other existentialists praise. Perhaps they are, and redemption is irrelevant. But Walt is also clearly now quite evil.

His toxic rant at Skyler on the phone after kidnapping their daughter, though perhaps also meant to provide Skyler with some legal cover, was nonetheless horribly hateful and hurtful. He meant every bottled-up word that finally spewed forth as he accused her of doubting, undermining, and otherwise failing to respect him.

Walt's wife Skyler

Walt has lied repeatedly, to himself and others, for the sake of elevating his horrific actions to something he imagines is noble. But he is on the run now, having made enemies of the sort that people who cook meth, and aspire to be kingpins, eventually confront. He cannot be part of society again, and we know he'll go down in a blaze, but not one of glory, surely. He cannot. That's not how morality plays work.

No one is perfectly innocent in Breaking Bad, or in life. Everyman himself is not completely innocent - we all have our faults, we are all human. But in Everyman, because the tally of good deeds outweighs the bad, he attains heaven.

It is a blueprint, a model for a life we can aspire to. Walter White serves the opposite role - he is a warning. Evil can creep up on us; we can choose it subtly. We sell our souls in bits and pieces. It can approach us banally, without our acknowledgement or notice. Then it can grip us and not let us go.

Walt's corruption is conclusive, and the very best we can hope for is that he doesn't take the child-like innocents with him.

Walt's account book is clear, and we know at least where he won't be going. This is meant as a lesson, this modern morality play. Don't become a Walter White - it's all too possible, and entirely too easy. And let there be no doubt. Walt is evil.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published16 August 2013