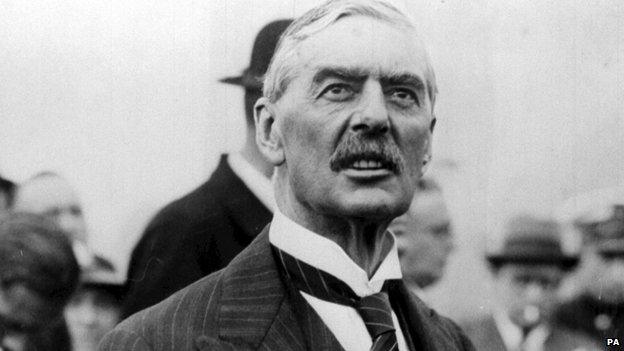

Was Neville Chamberlain really a weak and terrible leader?

- Published

Seventy-five years after the Munich Agreement signed with Hitler, the name of Neville Chamberlain, British prime minister at the time, is still synonymous with weakness and appeasement. Is this fair, asks historian Robert Self.

During his 21-hour filibuster denouncing President Barack Obama's healthcare law, popularly known as Obamacare, last week, Ted Cruz, the conservative Republican senator for Texas, claimed that Neville Chamberlain had once told the British people, "Accept the Nazis. Yes, they'll dominate the continent of Europe but that's not our problem."

Admittedly Cruz's speech was notable more for its near record-breaking length than its historical understanding, but this derogatory reference reflects the continuing potency of a well-established conventional wisdom assiduously propagated by Chamberlain's detractors after his fall from the premiership in May 1940. As Churchill is once supposed to have quipped, "Poor Neville will come badly out of history. I know, I will write that history".

In his influential account The Gathering Storm, published in 1948, Churchill characterised Chamberlain as "an upright, competent, well meaning man" fatally handicapped by a deluded self-confidence which compounded an already debilitating lack of both vision and diplomatic experience. For many years, this seductive version of events remained unchallenged and unchallengeable.

"Neville Chamberlain told the British people to accept the Nazis"

As Cruz's comments illustrate, Churchill's caricature of the 1930s, painted in compelling monochromatic shades of black and white, good versus evil, courage in "standing up to Hitler" versus craven appeasement, continues to strike a responsive note even today.

The Munich agreement, which later came to symbolise the evils of appeasement, was signed 75 years ago, in the early hours of 30 September. At Munich, Britain and France acquiesced in the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia and the transfer of its Sudeten region to Germany in face of Hitler's increasingly bellicose threats of military action. Chamberlain's hopes that this humiliating sacrifice would satisfy Hitler's last major territorial demand and thus avert another catastrophic war were dashed within four months.

After this monumental failure of policy Chamberlain's name became an abusive synonym for vacillation, weakness, immoral great-power diplomacy and, above all, the craven appeasement of bullies - whatever the price in national honour. Despite his many achievements in domestic policy, therefore, ultimately Chamberlain's reputation remains indelibly stained by Munich and the failure of his very personal brand of diplomacy.

As he confessed in the Commons at the outbreak of war, "Everything I have worked for, everything that I have hoped for, everything that I have believed in during my public life, has crashed into ruins."

Posterity has judged him accordingly - to the detriment of any more balanced evaluation of the man and the problems he confronted during the late 1930s.

In retrospect, the depressing reality is that there was probably no right answer to the crucial problems confronting British policy makers at the time. By the mid-1930s Britain was defending a vast and vulnerable empire encompassing a quarter of the world's territory and population, with the dismally depleted military resources of a third-rate power.

Worse still, since 1934 the Cabinet had grimly recognised that it was "beyond the resources of this country to make proper provision in peace for defence of the British Empire against three major powers in three different theatres of war". Furthermore, the threat posed separately by Japan, Germany and Italy was compounded by the conviction that war with any one of them would inevitably provoke opportunistic "mad dog" acts by the others.

As the leader of a militarily weak and overstretched empire, such fears were crucial in shaping Chamberlain's strategy, but this meant steering a course within the relatively narrow parameters defined by a complex inter-related web of geo-strategic, military, economic, financial, industrial, intelligence and electoral constraints.

Despite interminable scholarly debate, no consensus has emerged - particularly about the degree of choice enjoyed by policy makers in the face of such threats and constraints.

Neville Chamberlain delivers his "piece of paper" speech, 1938

Yet notwithstanding Chamberlain's personal predilection for negotiation, what is beyond question is that he perceived himself to be a prisoner of forces largely beyond his control. As he noted stoically in January 1938, "In the absence of any powerful ally, and until our armaments are completed, we must adjust our foreign policy to our circumstances, and even bear with patience and good humour actions which we should like to treat in a very different fashion."

His pragmatic response to this conundrum was a "double policy" of rearmament at a pace the economy could sustain, while simultaneously seeking better relations with the dictators in the belief that only by redressing Germany's legitimate grievances would it be possible to remove the military threat - or failing that, to expose Hitler as an insatiable megalomaniac bent on world domination. As Chamberlain told Lord Halifax, his foreign secretary, the underlying strategy was to hope for the best while preparing for the worst.

When seen from this perspective, Chamberlain faced a brutally simple choice at Munich. Was Britain prepared to threaten Germany with war on behalf of a state which it certainly could not save and which would probably never be resurrected in its existing form? There was the absolute certainty that any attempt to do so would provoke a ruinous and probably un-winnable war which would slaughter millions, bring in Japan and Italy, destroy the British Empire, squander its wealth and undermine its position as a Great Power.

When confronted by this unenviable dilemma, Chamberlain concluded that such an outcome would be far more disastrous for the empire, Europe and the long-term victory of good over evil than territorial concessions in the Sudetenland which Britain could not prevent and to which Germany had some ostensibly legitimate claim.

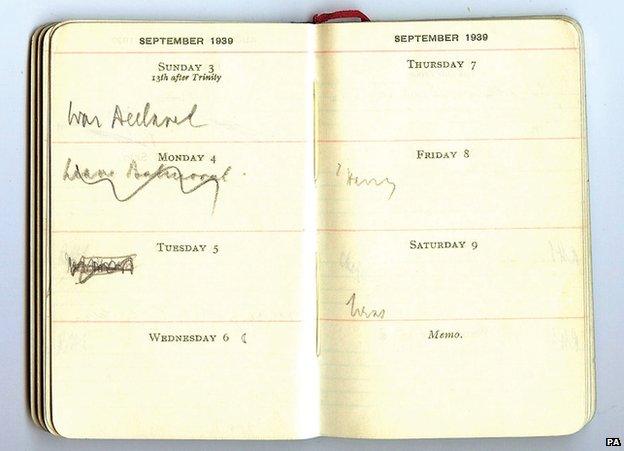

Neville Chamberlain's diary for the week Britain declared war on Germany

Despite the complete failure of his efforts to preserve peace, Chamberlain went to his grave in November 1940 confident that history would eventually vindicate his policy and rehabilitate his reputation.

Alas, this was his greatest miscalculation of all. "Poor Neville" did come badly out of history - and largely because Churchill wrote that history to ensure his own carefully crafted version of the 1930s would become the one indelibly etched upon the collective consciousness.

As Cruz's comments illustrate, the abiding popular image of Neville Chamberlain remains that of a naive tragicomic figure clutching a worthless piece of paper inscribed with the legend "Peace for our time".

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external