Why Finland loves saunas

- Published

The only Finnish word to make it into everyday English is "sauna". But what it is, and how much it means to Finns, is often misunderstood - and it's definitely not about flirtation or sex.

In a dimly lit wood-panelled room, naked men sit in silence, sweating. One beats himself repeatedly with birch branches. Another stands, takes a ladle of water and carefully pours it over the heated stones of the stove in the corner.

There is a hissing noise.

Within seconds a wave of moist heat creeps up around your ankles and over your legs before enveloping your whole body. Your pores open up and sweat covers you from head to toe.

This bathing ritual has been performed across Finland for thousands of years, ever since the first settlers dug a ditch in the ground and heated a pile of stones. Water was thrown on the hot stones to give off a vapour known as loyly.

Each sauna is considered to have its own character and its own distinctive loyly. The better the loyly, the more enjoyable the sauna.

For those working in the fields in harsh conditions, the sauna provided welcome relief to wash and soothe aching muscles.

These warm wooden rooms could be used at lower temperatures too, and were at the heart of the major events of a Finn's life.

Women gave birth in them because the walls of traditional smoke saunas were lined with naturally bacteria-resistant soot, making them the cleanest room in the house.

Saunas were also the place for purification rituals before marriage, and the bodies of the dead were washed and prepared for burial on the wooden benches.

For many Finns the sauna was the holiest room in the house and the one most closely associated with their wellbeing.

"Finns say the sauna is a poor man's pharmacy," says Pekka Niemi, a 54-year-old from Helsinki, who spends about three hours a day in the sauna, six days a week. "If a sick person is not cured by tar, spirits or sauna, then they will die," he adds, quoting a Finnish proverb. ("Spirits" here means strong alcohol, while tar was historically used as an antiseptic.)

Today, Finland is a nation of 5.3 million people and 3.3 million saunas, found in homes, offices, factories, sports centres, hotels, ships and deep below the ground in mines.

While Pekka Niemi's sauna habit may be exceptional, 99% of Finns take at least one a week, and much more when they visit their summer cottage in the countryside. Here the pattern of life tends to revolve around the sauna, and a nearby lake used for cooling off.

Don't imagine, though, that the sauna is purely a place for fun and games. It certainly would not have been in times gone by.

"Children were taught to behave in a sauna as if they were in church," says Jarmo Lehtola approvingly. He is from Saunaseura, the Finnish Sauna Society, an organisation dedicated to upholding and preserving traditional sauna culture.

Founded in 1937, this private club of 4,200 members is based on an island a 15-minute bus ride from central Helsinki. Surrounded by a silver birch forest, it overlooks the tranquil Baltic Sea.

A sign on the front door instructs you to switch off your mobile phone.

At Saunaseura's private sauna near Helsinki

"Sauna is for your mind. It really helps you to calm down in a modern society where it is never quiet," says Lehtola. "You enter this meditative place. It's dark and it's usually so hot that you don't want to speak."

There are some basic rules. No eating or drinking is allowed in the sauna and if you speak you should not discuss your job, title or religion. Members can choose between an electric sauna, two wood-burning saunas and three smoke saunas - all varying in heat and intensity.

Most Finns consider traditional smoke saunas to be the best because of the very soft loyly they produce. They take about five hours to heat and produce soot which covers the wooden walls in a thick black layer. The benches are scrubbed clean but bathers are advised not to lean against the wall, unless they want to get a sooty back.

Unlike wood-burning saunas, the smoke saunas use a stove without a chimney. The smoke clears through a small hole in the ceiling before you enter. You can still smell it - a pleasant sensation which transports your mind to the forest - but you do not see it or feel it in your eyes.

No clothes or swimsuits are allowed, for the same reason that you would not wear anything in the bath or shower. Every part of the body needs to be properly cleaned.

Men and women visit the sauna separately, unless they are members of the same family. Parents go with their children, and everyone is comfortable with that - at least until the children become teenagers, when they tend to use the sauna alone, or with friends.

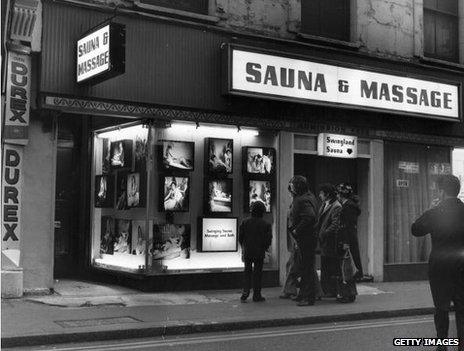

The word carried sexual connotations in 1970s Soho

There is one widespread misconception that Lehtola is very keen to dispel. "It's nothing to do with sex in Finland," he says emphatically.

"But in places like Germany in the 1970s and 80s it was all to do with sex."

Lehtola insists he has never enjoyed a sauna beyond Finland's borders, despite trying them in many countries.

Truth to tell, he would not be happy with some of Helsinki's public saunas either. Two - Kotiharju and Arla - date from the 1920s and can be found in Kallio, a traditionally working class district.

Factory workers who lived in homes without bathing facilities used to visit these saunas to relax, socialise and be scrubbed clean by washerwomen. Now the area's new inhabitants - students, artists and adventurous tourists - come to sweat and drink cold beer.

At Arla, the mood contrasts sharply with Saunaseura's contemplative atmosphere. The famed Finnish reserve is nowhere to be seen. People seem to enjoy talking to complete strangers in the nude, as long as it's painfully hot.

And there is alcohol too. Outside in a courtyard people wrapped in towels open bottles of beer, as steam rises from their bodies.

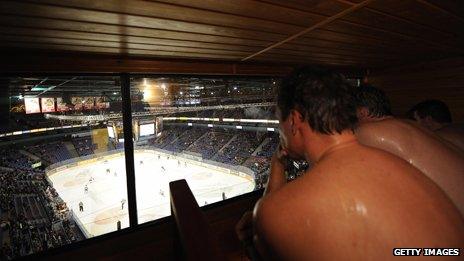

Watching ice hockey from the warmth of a stadium sauna box in Helsinki

There used to be more than 100 public saunas in Helsinki, with one on almost every street corner. But the number began to decline in the 1950s when people began to buy their own homes, complete with private sauna.

The capital now has just four public saunas. One is the brand new Kulttuurisauna, or Culture Sauna - the first to have been built in the city for half a century.

Despite the heat, which can reach up to 160C (320F), Finns insist saunas cool down tense situations.

The Finnish parliament has its own sauna chamber for MPs to debate in, and all Finnish diplomatic and consular missions around the world have their own sauna.

Former president and Nobel peace prize laureate Martti Ahtisaari used sauna diplomacy - diplomatic meetings in the sauna - to move forward negotiations from Tanzania to Indonesia. During the Cold War, Urho Kekkonen - who served as president for 26 years - negotiated with Soviet diplomats in the sauna at his official residence.

All Finns have a favourite sauna.

For 35-year-old Minna Kurjenluoma it is the one her grandfather built for the family in the 1940s on the shore of a lake next to a forest in north-east Finland.

"It's very traditional and basic. There's no electricity and it's always very dim so you need to have a couple of candles," she says. "The loyly is the best because it's very soft, and moist enough because all of the wooden parts of the sauna are very old and soft."

For Kurjenluoma, the sauna played a significant part in growing up.

"To share a sauna with your grandmother, you've seen the body of an older female without clothes and I think that is great because you don't see that often. It's very healthy to see different types of breasts and bums that aren't shown in the magazines."

After cooling off in the Baltic Sea at Saunaseura, I ask Jarmo Lehtola what life would be like without saunas.

"There wouldn't be a Finland without the sauna. It's in our DNA," he says.

"If somebody wants to understand what it is to be a Finn then they have to understand what a sauna is. If you do not experience sauna then you do not experience Finland."

Saunas - and the subsequent outdoor dips - are popular year round

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published2 December 2022