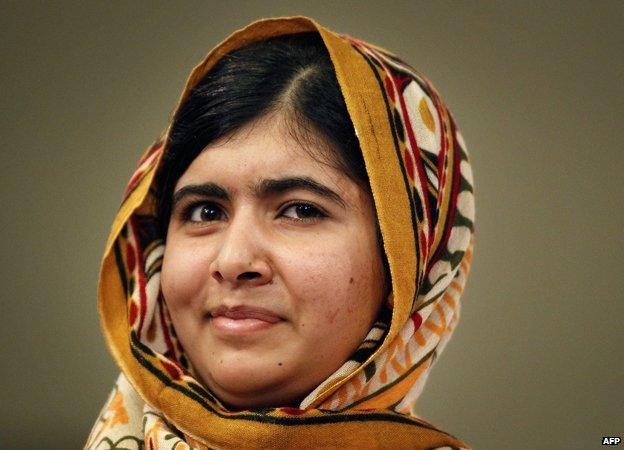

Malala: The girl who was shot for going to school

- Published

One year ago schoolgirl Malala Yousafzai was shot in the head by Taliban gunmen - her "crime", to have spoken up for the right of girls to be educated. The world reacted in horror, but after weeks in intensive care Malala survived. Her full story can now be told.

She is the teenager who marked her 16th birthday with a live address from UN headquarters, is known around the world by her first name alone, and has been lauded by a former British prime minister as "an icon of courage and hope".

She is also a Birmingham schoolgirl trying to settle into a new class, worrying about homework and reading lists, missing friends from her old school, and squabbling with her two younger brothers.

She is Malala Yousafzai, whose life was forever changed at age 15 by a Taliban bullet on 9 October 2012.

I have travelled to her home town in Pakistan, seen the school that moulded her, met the doctors who treated her and spent time with her and her family, for one reason - to answer the same question barked by the gunman who flagged down her school bus last October: "Who is Malala?"

The Swat Valley once took pride in being called "the Switzerland of Pakistan". It's a mountainous place, cool in summer and snowy in winter, within easy reach of the capital, Islamabad. And when Malala was born in 1997 it was still peaceful.

Just a few hours' driving from Islamabad brings you to the foot of the Malakand pass, the gateway to the valley. The winding road up to the pass leaves the plains of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, formerly known as the North-West Frontier Province, far below.

I remember it well from childhood holidays in Pakistan. But my latest trip felt very different - the BBC crew made the journey with a military escort. Although the Pakistan army retook control of Swat from the Taliban in 2009 and it is arguably now safer for foreigners than some other areas, the military clearly didn't want to take any chances.

Historically, the north-west has been one of Pakistan's least developed regions. But Swat, interestingly, has long been a bright spot in terms of education.

Until 1969, it was a semi-autonomous principality - its ruler known as the Wali. The first of these was Miangul Gulshahzada Sir Abdul Wadud, appointed by a local council in 1915 and known to Swatis as "Badshah Sahib" - the King. Although himself uneducated, he laid the foundation for a network of schools in the valley - the first boys' primary school came in 1922, followed within a few years by the first girls' school.

The trend was continued by his son, Wali Miangul Abdul Haq Jahanzeb, who came to power in 1949. Within a few months, he had presented the schoolgirls of Swat to the visiting prime minister of Pakistan, Liaquat Ali Khan, and his wife Raana. As his grandson Miangul Adnan Aurangzeb says: "It would have been unusual anywhere else in the [North-West] Frontier at that time, but in Swat girls were going to school."

The new Wali's focus soon turned to high schools and colleges, including Jahanzeb College, founded in 1952, where Malala's father, Ziauddin Yousafzai, would study many years later. Soon, Swat became known across Pakistan for the number of professionals it was producing - especially doctors and teachers. As Adnan Aurangzeb says, "Swat was proud of its record on education… one way to identify a Swati outside of Swat was that he always had a pen in his chest pocket, and that meant he was literate."

Against this backdrop, the fate that befell the schools of Swat in the first years of the 21st Century is particularly tragic.

By the time Malala was born, her father had realised his dream of founding his own school, which began with just a few pupils and mushroomed into an establishment educating more than 1,000 girls and boys.

Malala Yousafzai: In Pakistan "we know that terrorists are afraid of the power of education"

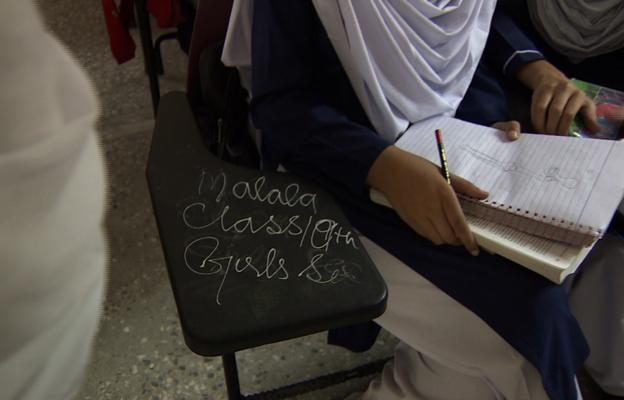

It is clear that her absence is keenly felt. Outside the door of her old classroom is a framed newspaper cutting about her. Inside, her best friend Moniba has written the name "Malala" on a chair placed in the front row.

This was Malala's world - not one of wealth or privilege but an atmosphere dominated by learning. And she flourished. "She was precocious, confident, assertive," says Adnan Aurangzeb. "A young person with the drive to achieve something in life."

In that, she wasn't alone. "Malala's whole class is special," headmistress Mariam Khalique tells me.

And from the moment I walk in, I understand what she means. Their focus and attention is absolute, their aspirations sky-high. The lesson under way is biology, and as it ends I have a few moments to ask the girls about their future plans - many want to be doctors. One girl's answer stops me in my tracks: "I'd like to be Pakistan's army chief one day."

Part of the reason for this drive to succeed is that only white-collar, professional jobs will allow these girls a life outside their homes. While poorly educated boys can hope to find low-skilled work, their female counterparts will find their earning power restricted to what they can do within the four walls of their home - sewing perhaps.

"For my brothers it was easy to think about the future," Malala tells me when we meet in Birmingham. "They can be anything they want. But for me it was hard and for that reason I wanted to become educated and empower myself with knowledge."

It was this future that was threatened when the first signs of Taliban influence emerged, borne on a tide of anti-Western sentiment that swept across Pakistan in the years after 9/11 and the US-led invasion of Afghanistan.

Like other parts of north-west Pakistan, Swat had always been a devout and conservative region, but what was happening by 2007 was very different - radio broadcasts threatening Sharia-style punishments for those who departed from local Muslim traditions, and most ominously, edicts against education.

The worst period came at the end of 2008, when the local Taliban leader, Mullah Fazlullah, issued a dire warning - all female education had to cease within a month, or schools would suffer consequences. Malala remembers the moment well: "'How can they stop us going to school?' I was thinking. 'It's impossible, how can they do it?'"

But Ziauddin Yousafzai and his friend Ahmad Shah, who ran another school nearby, had to recognise it as a real possibility. The Taliban had always followed through on their threats. The two men discussed the situation with local army commanders. "I asked them how much security would be provided to us," Shah recalls. "They said, 'We will provide security, don't close your schools.'"

It was easier said than done.

By this time, Malala was still only 11, but well aware of how things were changing.

"People don't need to be aware of these things at the age of nine or 10 or 11 but we were seeing terrorism and extremism, so I had to be aware," she says.

She knew that her way of life was under threat. When a journalist from BBC Urdu asked her father about young people who might be willing to give their perspective on life under the Taliban, he suggested Malala.

The result was the Diary of a Pakistani Schoolgirl, external, a blog for BBC Urdu, in which Malala chronicled her hope to keep going to school and her fears for the future of Swat.

She saw it as an opportunity.

"I wanted to speak up for my rights," she says. "And also I didn't want my future to be just sitting in a room and be imprisoned in my four walls and just cooking and giving birth to children. I didn't want to see my life in that way."

The blog was anonymous, but Malala was also unafraid to speak out in public about the right to education, as she did in February 2009 to the Pakistani television presenter Hamid Mir, who brought his show to Swat.

"I was surprised that there is a little girl in Swat who can speak with a lot of confidence, who's very brave, who's very articulate," Mir says. "But at the same time I was a bit concerned about her security, about the security of her family."

At that time it was Ziauddin Yousafzai, Malala's father, who was perceived to be at the greatest risk. Already known as a social and educational activist, he had sensed that the Taliban would move from the tribal areas of Pakistan into Swat, and had often warned people to be on their guard.

Malala herself was concerned for him. "I was worried about my father," she says. "I used to think, 'What will I do if a Talib comes to the house? We'll hide my father in a cupboard and call the police.'"

No-one thought the Taliban would target a child. There were however notorious incidents where they had chosen to make an example of women. In early 2009, a dancer was accused of immorality and executed, her body put on public display in the centre of Mingora. Soon afterwards, there was outrage across Pakistan after a video emerged from Swat showing the Taliban flogging a 17-year-old girl for alleged "illicit relations" with a man.

Ziauddin Yousafzai must have known that Malala's high profile in the valley put her at some risk, even though he could not have foreseen the outcome.

"Malala's voice was the most powerful voice in Swat because the biggest victim of the Taliban was girls' schools and girls' education and few people talked about it," he says. "When she used to speak about education, everybody gave it importance."

By the time Malala was shot in 2012, the worst days of Taliban power in Swat had receded. A high-profile military operation had cleared out most militants but others had stayed behind, keeping a low profile.

"Life was normal for normal people, but for those people who had raised their voice, it was now a risky time," says Malala.

She was one of those people.

On the afternoon of 9 October, she walked out of school as normal and boarded a small bus waiting outside the gates. These vehicles are seen everywhere in Mingora - a little like covered pickup trucks, open at the back, with three lines of benches running the length of the flatbed. Each could carry about 20 people and would be waiting to take the girls and their teachers home at the end of the school day.

In Malala's case, it was only a short journey, past a small clearing where children played cricket, and along the canal bank to her house. Once she had walked, but then her mother, Tor Pekai, intervened. "My mother told me, 'Now you are growing up and people know you, so you must not go on foot, you must go in a car or a bus so then you will be safe,'" Malala says.

That day, she was in the middle of her exams, and had a lot on her mind. But there was still the usual after-school chat and gossip to share with Moniba, who was sitting next to her. But as the bus progressed along its route Malala says she did notice something unusual - the road seemed deserted. "I asked Moniba, 'Why is there no-one here? Can you see it's not like it usually is?'"

Moments later, the bus was flagged down by two young men as it passed a clearing, only 100 yards from the school gates. Malala doesn't recall seeing them but Moniba does. To her they looked like college students.

Then she heard one ask: "Who is Malala?" In the seconds between that question and the firing beginning, Moniba at first wondered if the men were more journalists in search of her well-known friend. But she quickly grasped that Malala had sensed danger. "She was very scared at that time,' she remembers. The girls looked at Malala, thereby innocently identifying her.

The two girls sitting on Malala's other side, Shazia Ramzan and Kainat Riaz, were also injured.

"I heard the firing, then I saw lots of blood on Malala's head," says Kainat. "When I saw that blood on Malala, I fell unconscious."

Moniba says the bus remained there for 10 minutes, before anyone came to the aid of the panic-stricken women and children.

When they reached hospital, it was assumed all four girls were wounded, because Moniba's clothing was drenched in her friend's blood.

News of the shooting spread quickly. Malala's father was at the Press Club when a phone call came to tell him one of his school buses had been attacked. He feared at once that it was Malala who had been targeted. He found her on a stretcher in the hospital.

.jpg)

Malala as she was stretchered to hospital

"When I looked towards her face I just bowed down, I kissed her on the forehead, her nose, and cheeks," he says. "And then I said, 'You're my proud daughter. I am proud of you.'"

Malala had been shot in the head and it was clear to everyone, including the Pakistan army, that her life was in danger. A helicopter was scrambled to airlift her to the military hospital in Peshawar - a journey that would eventually take her not just away from Swat but away from Pakistan.

The Combined Military Hospital in Peshawar is the best medical facility in the region, treating not just military personnel but their families too. As he flew in with Malala, Ziauddin Yousafzai was braced for the worst, telling relatives at his family home in rural Swat to make preparations for a funeral. "It really was the most difficult time in my life," he says.

From the helipad, Malala was brought in by ambulance and placed in the care of neurosurgeon Col Junaid Khan.

"She was initially conscious, but restless and agitated, moving all her limbs," he says. The entry wound of the bullet was above her left brow. From there it had travelled down through her neck and lodged in her back.

Malala was treated as a severe head injury case and placed under observation. After four hours, she deteriorated visibly, slipping towards unconsciousness. A scan revealed a life-threatening situation - her brain was swelling dangerously and she would need immediate surgery.

"The part of the brain involved was concerned not only with speech but also giving power to the right arm and leg," Khan says. "So contemplating surgery in this very sensitive area can have risks. The person can be paralysed afterwards."

Nevertheless, he told Malala's father that surgery was vital to save her life - a portion of her skull had to be removed to relieve pressure on the brain.

The procedure began with shaving part of Malala's hair, and then cutting away the bone, before placing the portion of removed skull inside her abdomen in case it could be later replaced. Blood clots and damaged tissue were extracted from inside the brain.

Before that day, Khan says, he had never heard the name Malala Yousafzai, but he was soon left in no doubt that he was treating a high-profile patient. Camera crews besieged the hospital compound as a tide of shock and revulsion spread through Pakistan.

TV presenter Hamid Mir looks back on the attack and the country's realisation that the Taliban were capable of shooting a young girl as a defining moment. "It gave me a lot of courage and strength [a sense] that enough is enough, now is the time to speak against the enemies of education," he says. "If they can target a little girl like Malala, they can target anyone."

From Adnan Aurangzeb, so closely connected to Swat and its people, there was anger - not just at the Taliban but at the government of Pakistan, which he held accountable for failing to protect Malala.

"She should have been under the protection of Pakistan," he says. "Not left to go unescorted like any normal student in an area infested with militants and Taliban."

Inside the intensive care unit in Peshawar, Malala appeared to respond well to the surgery. Her progress was by now being followed not just in Pakistan but around the world. In Islamabad, the army chief General Ashfaq Kayani was taking a keen interest, but wanted a definitive and independent opinion on Malala's chances.

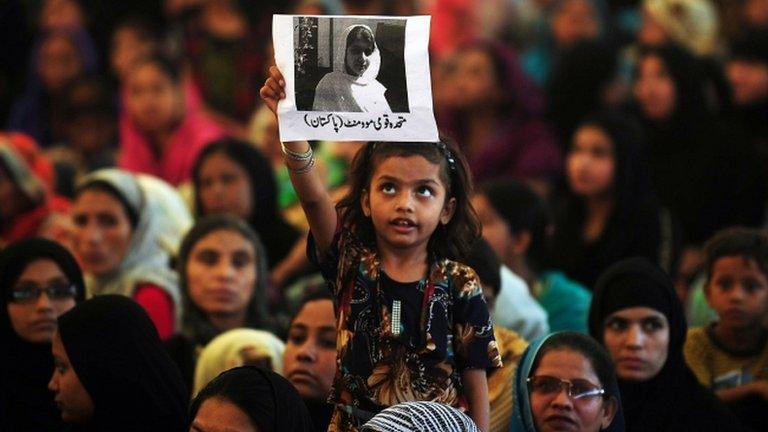

A vigil for Malala in Karachi as she recovered in hospital

As it happened, his officers were looking after a team of British doctors at the time - a group from Birmingham who had come to Pakistan to advise the army on setting up a liver transplant programme. The multi-disciplinary team was led by emergency care consultant Javid Kayani, a British Pakistani who maintains close links with the land of his birth.

When the request for help came through, Kayani knew which one of the team he wanted to take with him to Peshawar on the helicopter that was standing by. Given Malala's age, paediatric intensive care specialist Fiona Reynolds was the obvious choice. Although she had her doubts about security in Peshawar, she had heard enough about Malala from news reports to feel the risk was worth taking. "She'd been shot because she wanted an education, and I was in Pakistan because I'm a woman with an education, so I couldn't say 'no,'" she says.

What the doctors discovered in Peshawar, though, was not encouraging. Although Malala had had what Reynolds calls "the right surgery at the right time", she was being let down by the post-operative care. A similar patient in the UK would have been having her blood pressure checked continuously via an arterial line - according to Malala's charts, hers had last been checked two hours earlier.

Reynolds' instinct told her that Malala could be saved, but everything depended on how she would be cared for.

"The quality of the intensive care was potentially compromising her final outcome, both in terms of survival and in terms of her ability to recover as much brain function as possible," she says.

That clinical opinion would be vital to Malala's future. An army intensive care specialist was sent to bolster the team in Peshawar, but when Malala deteriorated further, she was airlifted again, this time to a bigger military hospital in Islamabad.

In the first hours after her arrival there, Fiona Reynolds remained very worried. Malala's kidneys appeared to have shut down, her heart and circulation were failing, and she needed drugs to support her unstable blood pressure. "I thought she was probably going to survive, but I wasn't sure of her neurological outcome, because she'd been so sick. Any brain damage would have been made worse."

As Malala gradually stabilised, over the next couple of days, Reynolds was asked for her opinion again - this time on her rehabilitation. She asked what facilities were available, knowing that acute medicine is often far ahead of rehab. That was indeed the case in Pakistan. "I said that if the Pakistan military and the Pakistan government were serious about optimising her outcome… I said that everything that she would need would be available in Birmingham."

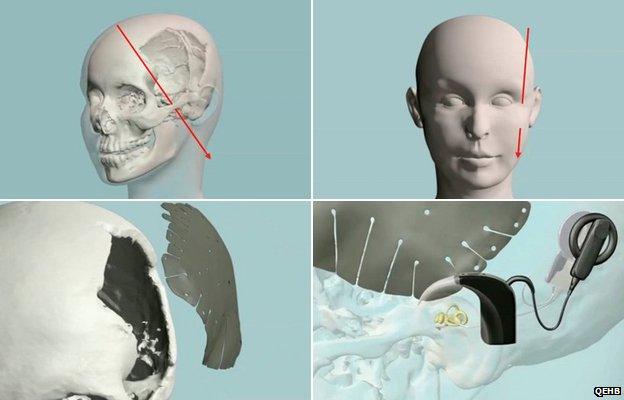

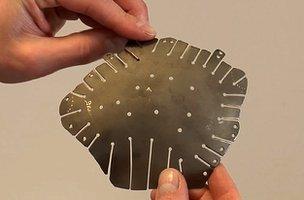

Graphics from the hospital showing the bullet's path, titanium plate and implant

On 15 October 2012, Malala arrived at the Queen Elizabeth hospital in Birmingham, where she would remain for the next three months. She had been kept in a medically induced coma, but a day later the doctors decided to bring her out of it. Her last memory was of being on a school bus in Swat - now she was waking up surrounded by strangers, in a foreign country.

"I opened my eyes and the first thing I saw was that I was in a hospital and I could see nurses and doctors," she says. "I thanked God - 'O Allah, I thank you because you have given me a new life and I am alive.'"

Malala's parents and brothers were still in Pakistan but Javid Kayani was standing at her bedside.

"When she woke up she had this very frightened look and her eyes were darting back and forth," he says.

"We knew she couldn't speak because she had a tube down her throat to assist her breathing. But I knew that she could hear so I told her who I was and I told her where she was, and she indicated by her eye movements that she understood."

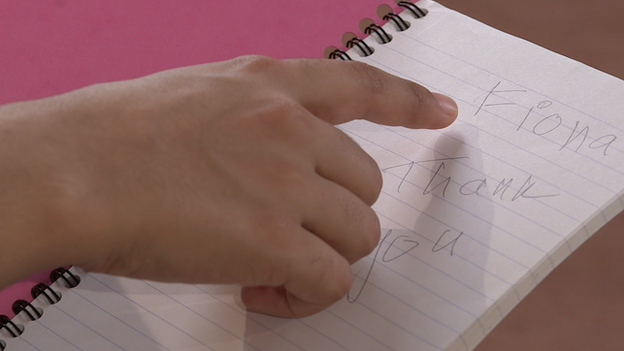

Malala then gestured that she wanted to write, so a pad of paper and a pencil were brought. She attempted to write, but she had poor control of the pencil - unsurprising for someone with a head injury. Instead, an alphabet board was found and Javid Kayani watched her point to the letters one by one.

"The first word that she tapped out was 'country'. So I assumed she wanted to know where she was and I told her she was in England. And then the next word was 'father' and I told her that he was in Pakistan and he'd be coming in the next few days. That was the limit of the conversation."

More "conversations" would take place with one of the few visitors allowed in - Fiona Reynolds, who brought Malala a pink notebook in which to write down her questions.

Malala showed it to me, It is a poignant reminder of her search for answers in that period, especially the page where she simply asks, "Who did this to me?"

For Reynolds, the fact that Malala was able to articulate her questions was a huge relief.

"I was hoping that her cognitive abilities would still be there. I was also hoping that she hadn't lost the power of speech. So the fact that she was mouthing words and writing - I thought she's not lost the ability to speak.

"And remember she was talking in her third language [Pashto is Malala's mother tongue, Urdu her second language], so her speech centre was pretty intact."

Malala would go on to make an outstanding recovery, a tribute not just to the quality of the care she received - but also, her doctors told me, to her own resilience and determination.

Once she was out of intensive care, doctors began to consider what could be done about the paralysis of the left side of her face, which had caused great distress to her parents when they were reunited with her in Birmingham. Malala's father felt she had lost her smile.

"When she used to try to smile I would look at my wife and a shadow would fall on her face, because she thought, 'This is not the same Malala I gave birth to, this is not the girl who made our lives colourful.'"

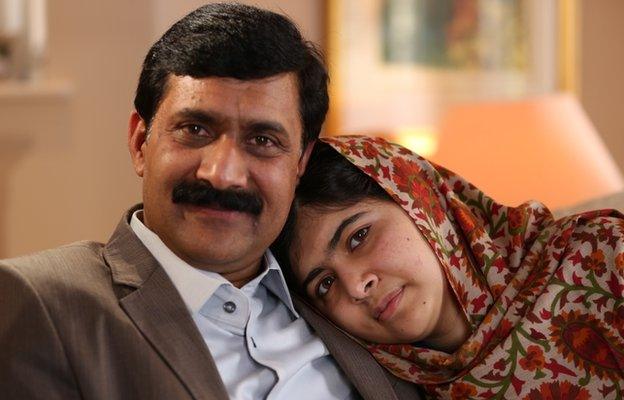

Malala with her father Ziauddin Yousafzai in Birmingham

Malala's ear specialist Richard Irving thinks that in those early weeks, she was troubled by her new appearance.

"She was very reluctant initially to speak, she preferred to be photographed from the good side," he says. "I think it probably did have an emotional impact on her, which she didn't really voice to anyone, but it's very easy to understand in a 15-year-old."

After tests and scans, Irving's view was that the facial nerve was unlikely to repair itself, but without surgery, he couldn't be sure exactly what state it was in. The procedure would be a lengthy one, and this time Malala was herself able to weigh up the risks.

A titanium plate used to repair Malala's skull

"She was in control," Irving says. "She would take advice from her father but she was making the decisions. She took a great interest in her medical care and didn't leave it to someone else."

During a 10-hour operation last November, he discovered that Malala's facial nerve had been entirely severed by the bullet and that a 2cm section of it was missing. For any movement to return to her face, the two ends of the nerve would have to be re-attached, but the missing section made it impossible to do this along the original route. Instead, Irving decided to expose the nerve and re-route it so it travelled a shorter distance.

In February this year, a further operation replaced the skull section removed by the surgeons in Pakistan, with a titanium plate. A cochlear implant was also inserted into Malala's left ear to correct damage to her hearing caused by the bullet. No further surgery is said to be required - her face should continue to improve over time, with the help of physiotherapy.

On 12 July, nine months after the shooting, came a major milestone - Malala stood up at the UN headquarters in New York and addressed a specially convened youth assembly. It was her 16th birthday and her speech was broadcast around the world.

"One child, one teacher, one book, one pen can change the world," she said.

How did it feel to speak in public once again - this time on a bigger stage than she could ever have imagined?

"When I looked at 400 youth and people from more than 100 countries… I said that I am not only talking to the people of America and the other countries, I am talking to every person in the world," she says.

Ziauddin Yousafzai remembers it as the biggest day of his life. For him, Malala's speech was an assault on negative perceptions of Pashtuns, of Pakistanis and of Muslims.

"She was holding the lamp of hope and telling the world - we are not terrorists, we are peaceful, we love education."

Malala was introduced to the audience in New York that day by former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, the UN's special envoy on global education.

He has no doubt about her power to focus attention on the bigger picture of nearly 60 million out-of-school children around the world. "Because of Malala," he says, "there is a public understanding that something is wrong and has got to be done."

There is even speculation she could be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The girl from Swat has gone global, but she still believes she can and will return home to Pakistan. Few would advise her to do that anytime soon. There are still fears for her security and also criticism that she attracts too much attention, especially in the West.

But she seems sanguine about any criticism. "It's their right to express their feelings, and it's my right to say what I want," she says. "I want to do something for education, that's my only desire."

The danger for Malala is that the more time she spends away from Pakistan, the less she will be seen at home as a true Pakistani, and the more she will be identified with the West. But she has little time for distinctions between East and West.

"Education is education," she says. "If I am learning to be a doctor would there be an eastern stethoscope or a western stethoscope, would there be an eastern thermometer or a western thermometer?"

-

1997:

Born in Swat Valley, Pakistan -

2009:

Wrote anonymous BBC blog about life under the Taliban -

2009-10:

Identity revealed in TV interviews and a documentary -

2011:

International Children’s Peace Prize nominee -

2012:

Shot in assassination attempt by Taliban -

2013:

Nobel Peace Prize nominee, named one of Time magazine’s most influential people

Still only 16, she has to balance being the world's most high-profile educational campaigner, in demand around the world, with the completion of her own schooling.

"I am still the old Malala. I still try to live normally but yes, my life has changed a lot," she tells me.

There are moments when she misses her old anonymity, but says it's "human nature" to want what you don't have.

She is an extraordinary young woman, wise beyond her years, sensible, sensitive and focused. She has experienced the worst of humanity, and the best of humanity - both from the medics who cared for her and the messages from many thousands of well-wishers.

I find one of those well-wishers in her own street in Swat, just outside the home that she never made it back to, on the afternoon she was shot. He is a young man called Farhanullah and he says the Taliban have blighted his life, destroying Swat's economic, social and educational fabric. Malala was "Pakistan's daughter", he says. "We should be proud that she has made such a big sacrifice for Pakistan."

I ask if he would like to send a message to Malala. Yes, he says. "She should continue her struggle. We are all with her."

The voice of the girl whom the Taliban tried to silence a year ago has been amplified beyond what anyone could have thought possible.

When I ask her what she thinks the militants achieved that day, she smiles.

"I think they may be regretting that they shot Malala," she says. "Now she is heard in every corner of the world."

Watch Mishal Husain's Panorama special Malala: Shot for Going to School on Monday 7 October at 20:30 BST on BBC One

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published10 October 2012

- Published12 July 2013

- Published4 January 2013