Why some Mexicans want to get out of Acapulco

- Published

Acapulco was once known as the place Hollywood stars went on holiday. But the area around the resort is now home to violent drugs gangs, and last month, the region was hit by devastating floods and mudslides that killed dozens of people.

Normally the high-pitched sound of children playing inside a sports hall would be a happy one.

But as we bustled past the armed guards on the door, muttering our introductions to the officials, it was clear this was no fun kids' day out.

These children, with their parents and grandparents watching on, were homeless, displaced by the days of non-stop rain and mudslides caused by two hurricanes hitting Mexico at once.

In emergency shelters across the country, from the western jungles of Oaxaca to the Gulf of Mexico, survivors are telling stories of having lost everything in the floods. But few have suffered as much as the people inside this particular building.

One woman had lost her four daughters, aged from two to ten years old, dragged away by the swollen river. Only the youngest's body had washed up.

On the patio of the sports hall, huddled underneath an awning, were the villagers of La Pintada, once a thriving coffee-growing village in the mountains of Guerrero, now a byword for the loss and destruction of Hurricane Manuel.

The local people had been eating an Independence Day lunch when tragedy struck. Their quiet anonymous lives were uprooted in an instant as a huge mudslide engulfed the streets and plazas, flattening their rickety homes and leaving at least 68 villagers dead.

It was the worst single event of the storms, and the victims, gathered in a tent on the outskirts of Acapulco, were staring into the middle distance, some of them barefoot, clutching naked children in their arms.

"There was nothing we could do," Margarito Hernandez said, as we took a seat on a bright yellow bench.

The young carpenter lost his father, his brother and his sister-in-law in the landslide when the truck they were travelling in was covered by the tonnes of earth that fell from the mountainside.

He was only saved because they had told him to put some tools away in his workshop while they ran an errand.

Margarito described how the mud was like a "swamp" and that "if you stepped on it, you'd go under too".

He told a harrowing tale of running through the streets fruitlessly searching for his father's pick-up until the terrible realisation of what had happened.

He found his mother on the floor of their home, hysterical with grief but had to leave her to trek with some of the other young men to the next town to get word to the authorities of what had happened.

Watch aerial footage of the affected area and the relief effort.

It is all too much for any 18-year-old to endure.

His final heartbreaking comment was that Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto had visited the shelter a day before and Margarito had spoken to him.

"What did you ask him for?" I asked. "A visa to the United States," he replied without a hint of irony. "I have aunts there, maybe I can finally meet them in person now."

As we were taken by helicopter to other affected areas, it was clear even without the hurricane damage why so many young men and women would try to escape this part of the world.

Over the noise of the rotor blades, I asked one of the soldiers if this was normally drug-trafficking territory, the mountains being the perfect altitude and climate for the production of Acapulco Gold, the region's famous strain of marijuana.

"Normally, yes. "Los Caballeros," shouted back the soldier, referring to The Knights Templar, a particularly violent and cult-like gang which operates in these hills.

Like everyone else, the cartels were being hampered by the floods. Another TV crew we know walked through waterlogged opium fields as the rains washed away illegal poppy plantations and farmers' maize crops alike.

The cartel's presence was another reason some communities were too frightened to leave their homes and make the trek to safety.

Acapulco, too, seems a shadow of its former self.

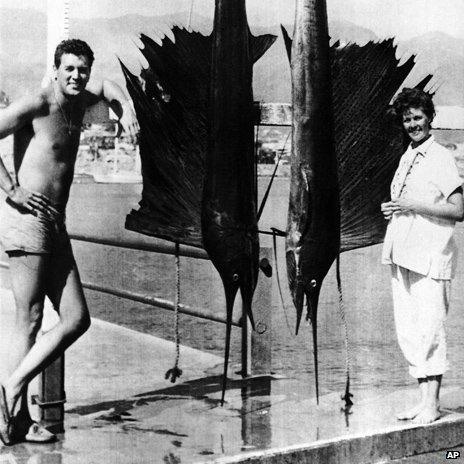

Rock Hudson was one of many Hollywood stars to holiday in Acapulco

The famous hideaway for the Hollywood stars, a place where the Clintons took their honeymoon, is looking washed up, an undercurrent of street crime never far from the crumbling facades of its beach-front hotels.

As we drove down the promenade known as the Costera, in search of a coffee shop with sufficient wi-fi to send our material back to London, we stopped at some traffic lights.

Suddenly, we heard the unmistakeable crack of gunfire - shots were being exchanged on the road behind. People began to scatter, others got out of their cars.

We could see the police with their automatic weapons raised, pointing at unknown assailants on the other side of the road.

With a gun battle in broad daylight in the heart of one of Mexico's tourist hotspots, while nearby villagers struggled with their grief, it is little wonder that Margarito wants to leave.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

From Our Own Correspondent, external: Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

- Published19 September 2013

- Published19 September 2013

- Published18 September 2013