The BBC's first Man in Moscow

- Published

The BBC tried to open a bureau in Russia during World War II but only succeeded some 20 years later - in 1963. In the last half century, much has changed for the BBC's Man in Moscow.

It was the summer of 1942 and Winston Churchill had flown to Russia to cement his wartime alliance with Joseph Stalin.

"We will continue hand in hand like comrades and brothers," Churchill declared on arrival, "until every vestige of the Nazi regime has been beaten into the ground."

Talk like this gave BBC bosses an idea. If Blighty and the Bolsheviks were suddenly best buddies, perhaps now was the moment to have a BBC correspondent based full-time in Moscow? So they sounded out the Soviets. And the answer came back: "Nyet!"

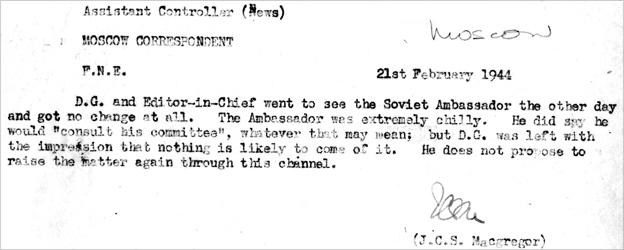

A memo from the Assistant Controller of News written at the time reads: "The DG and editor-in-chief went to see the Soviet ambassador the other day and got no change at all. The Ambassador was extremely chilly. DG was left with the impression that nothing is likely to come of it."

Mind you, it wasn't only Stalin who poured cold water on the idea.

"I think all Moscow cover is a waste of time and money," argued the BBC Central European Correspondent. It was his job to report on Russia from the safety, and coffee-shop comfort of Vienna.

In 1961 he tried to knock the whole idea on the head in a memo to his editor:

"It is impossible in the USSR to get either official or unofficial reaction to anything except through the pages of the press the next day. Though this is often forgotten in London where it is naturally assumed correspondents will be able to go and talk to the renowned man-in-the-street. They can't. The opportunities for being a journalist are very slight indeed and to an experienced man this is very annoying."

But when Soviet censorship eased under Nikita Khrushchev, the temptation to establish a permanent presence behind the iron curtain became irresistible and in 1963 the BBC finally opened a Moscow bureau.

Erik de Mauny was the obvious choice for the BBC's first resident correspondent in the USSR. Not only did he have plenty of foreign reporting experience (previous postings included Vienna, Beirut and Washington), he also had a university degree in Russian. The BBC bought him a car, a dark green Humber Super Snipe, which had been specially adapted to cope with the cold. And to keep himself warm, the intrepid reporter had brought with him two key items - an ankle-length suede coat from Moss Bros and a pair of RAF flying boots.

Erik de Mauny braves a snowstorm to report on the impending Communist Party Congress in 1965

De Mauny wrote about his Moscow experiences in a book, Shouting Through the Static. Sadly, he died before it could be published. The manuscript reads like the screenplay for a James Bond film. Particularly the account of a scoop with a spook - his exclusive interview in 1964 with the spy, Kim Philby.

The two men spent six hours in Philby's hotel suite getting drunk on vodka, wine and Armenian cognac, while Philby's KGB minder waited patiently in the corridor. Then de Mauny had a tough decision to make.

I woke at 09:00 next morning with throbbing temples and with a realisation that I was in a dilemma. Should I send a news despatch to London about my meeting with Kim? What was more, should I mention it to any of my close colleagues? I knew I had a scoop, if I chose to play it that way, because apart from one brief sighting by a Reuters' correspondent some months earlier, no-one had tracked Kim down, still less talked to him at length as I had done. Nevertheless, I decided to wait. A news despatch would certainly make an impact, but it was highly likely to prove a nine-days wonder. I seemed to me sensible to keep my powder dry and wait to see whether my encounter with Kim might yield long-term benefits.

After careful thought, however, I decided that the Embassy ought to be informed. So a bit later that morning, my hangover having subsided, I drove down to the big pseudo-Gothic mansion on the river embankment opposite the Kremlin. I found the Minister, Tom Brimelow, in his office and while we made small talk I slipped him a piece of paper on which I'd written: "I saw Kim Philby last night. Thought you might like to know about it." Tom contemplated this without emotion, but a few moments later he said, "That reminds me - I must have a word with the ambassador. I shan't be long." He was back a moment or two later with the ambassador, Sir Humphrey Trevelyan, who gave me a brief nod. Then, with Tom leading, we made our way in silence down to the Embassy "safe room", a small basement room enclosed in an electronic shield in which one could talk without fear of being bugged...

A day or so later, as I was crossing the courtyard (at home), I was intercepted by one of the first secretaries from the embassy, who handed me a folded piece of paper. "From the ambassador," he said, adding in a low voice, "better put it down the loo when you've read it." I opened the paper and saw that it contained a single typewritten sentence: "London advises break off contact."

In my role as Moscow correspondent I have never had to scribble secret notes to embassy officials or participate in drinking sessions with secret agents. And yet, 50 years on, Moscow correspondents are still chasing spy stories. After all, espionage didn't end when the Cold War did.

Like most foreign journalists in Moscow at the time, De Mauny assumed that his apartment was bugged. As frustrating as that may have been for his family, this created comical situations. During a visit to Moscow by the BBC's director general, Hugh Greene, and the head of BBC foreign liaison, Donald Stephenson, the correspondent invited his bosses - and British ambassador Sir Humphrey Trevelyan - back to his flat for a drink.

Suddenly, Donald caught my eye. "I say, old boy, there's one thing I've been meaning to ask," he said. "Is it true that Mrs Furtseva is Khrushchev's mistress?"

Before I could utter a word, Sir Humphrey had cut in. "Mrs Furtseva is the Soviet Minister of Culture," he said firmly.

"Yes, I know," said Donald, not to be put off, "but is she Khrushchev's mistress?"

The ambassador directed his gaze at the ceiling, and, this time in loud, decisive tones, once more declared: "Mrs Furtseva is the Soviet Minister of Culture!"

I saw Donald open his mouth, as if to make a further try. Then, fortunately, the penny dropped. There was a moment of embarrassed silence, and we turned to other topics.

It was from the Central Telegraph Office on Gorky Street that Erik de Mauny filed many of his stories. This sprawling construction was the communications hub of the Soviet Union - people came here to send telegrams, telexes, letters and to make long-distance calls. De Mauny would often book telephone lines to London hours in advance. At the allotted time he would turn up, go into a booth and voice his despatch. At least, that was the theory. But sometimes the lines never came up. This happened so often that de Mauny even wrote to the Soviet communications minister to complain.

Since then, of course, technology has moved on. Today the Moscow correspondent can use his smart phone to broadcast live radio in quality, even to transmit TV pictures. As for the Central Telegraph, you can still send telegrams from there. But all those old Soviet telephone booths have been ripped out and replaced by a bank and a cafe.

I checked out the cafe. The food is adequate, but not as exotic as some of the delicacies de Mauny was treated to in the 1960s. All foreign correspondents and the entire diplomatic corp based in Moscow would get invited to lavish banquets at the Kremlin. De Mauny interpreted it as an attempt by Khrushchev to impress the outside world:

The chosen guests and members of the politburo were grouped behind the top table, while the rest of us circulated between the two long side tables. All three tables were lavishly laden with the most succulent dishes imaginable, from mounds of the finest Iranian caviar from the southern Caspian - plump globules of grey imperial malosol in crystal dishes surrounded by crushed ice - to great platters of smoked salmon and sturgeon... Meanwhile, waiters hurried among the guests with trays of delicious hot snacks, ice-cream and champagne, coffee and Armenian cognac.

The Moscow correspondent today has fewer opportunities to dine in such decadence at the heart of Russian power. But, on the positive side, he has far more options for eating out than de Mauny ever did - today Moscow is awash with cafes, coffee shops and restaurants. The supermarkets are better stocked, too, and many of them are open round the clock. The Soviet concept of "defitsit" or "shortage" has, thankfully, passed into history.

Erik de Mauny and his wife report on one of Moscow's rare major fashion shows

Erik de Mauny spent three years in Moscow. During that time he covered such momentous events as the first woman cosmonaut in space and Nikita Khrushchev's fall from power. In 1966 he left Moscow and moved to the BBC's Paris bureau. But six years later he was back in the USSR for a second stint.

In 1974 he reported the arrest of the dissident writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Only hours before, de Mauny had recorded Solzhenitsyn reading from his book, Gulag Archipelago. Now he needed to get that tape to London, fast.

And it was de Mauny's wife Elizabeth, a fellow journalist, who came up with an ingenious solution. In a souvenir shop she bought a cassette recording of the Red Army choir. She took out the tape and put the Solzhenitsyn recording in its place. Then a family friend who was returning to London smuggled it out. Collectively they had beaten the system - with a little help from the Soviet military's finest voices.

Having read de Mauny's memoirs, I'm struck both by what has changed in Russia over the last 50 years and by what hasn't. As a foreign correspondent based in Moscow, Erik de Mauny wasn't allowed to travel more than a few miles out of the Soviet capital without permission from the Soviet authorities. I have much more freedom to move around, although even today some parts of the country are still off-limits to me. And yet today, just like in 1963, dealing with officialdom can be problematic. I sense that many officials continue to view Western journalists with deep suspicion. De Mauny wrote that there were "so many contradictions between the warmth and generosity of individual friends and the sheer heartlessness of the system". That rings true now today. Russians who don't fit in with "the system" or who openly criticise it run the risk of being identified as troublemakers, even enemies of Russia.

But there is one story in Russia today which I'm certain Erik de Mauny would have gained great pleasure and pride from telling. And it's 700 miles east of Moscow.

Marc de Mauny: "My father was completely fascinated with Russia"

I fly to the city of Perm in the Ural Mountains and attend a rehearsal at the Perm Opera and Ballet Theatre. This is one of the oldest and most successful musical theatres in Russia. And the general manager and executive producer here is Marc de Mauny, the son of the BBC's first Moscow correspondent. Marc was just three when his father's second posting to Moscow ended in 1974. But, years later, he would return to study music at the St Petersburg Conservatory. He became fascinated by Russia, just like his father.

"My father loved Russian culture, literature and music, and I think, unwittingly, he passed that on to me," Marc says. "I didn't wake up to that until I was 16 or 17 and wondering where to go for my gap year and what to study at university. And it came to me in a blinding flash that I'd like to study Russian and travel in Russia and discover this country which I'd heard so much about from my father. But I had grown up with Russia and the Soviet Union very much present as this vast, mysterious land. It was an emotional involvement. Russia is an emotional place."

In a tiny practice room, spellbound, I watch a soloist putting heart and soul into a piece from Madame Butterfly. And I have to agree - Russia is an emotional place. This is a country of big hearts, great talents. But also huge problems and deep disappointments.

Russia is beauty and beast. For the Moscow correspondent the challenge was, and always will be, to paint a complete picture.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external